Why Barbara Comyns is the best English novelist you’ve never heard of

The novels of Barbara Comyns draw you in from their strange, beguiling first sentences. Take 1954’s Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead, for example, which begins: “The ducks swam through the windows.” Or 1950’s Our Spoons Came From Woolworths: “I told Helen my story and she went home and cried.” Her wartime dispatch Mr Fox, written in the 1940s but published in 1987, starts: “The other people in the house where I lived didn’t like me. I expect it was because I was living with a man I wasn’t married to.” And The Vet’s Daughter (1959), her very best novel, begins: “A man with small eyes and a ginger moustache came and spoke to me when I was thinking of something else.” I mean, come on. Don’t you just want to read them all right now?

Before that, though, you might be thinking: but… I don’t have the faintest idea who Barbara Comyns is. Writing at the same time as the likes of Elizabeth Jane Howard, Daphne du Maurier, Elizabeth Taylor, Iris Murdoch and Stella Gibbons, she is one of the most thrillingly unique mid-century English novelists. But somehow, she cuts a lonely figure – not part of any particular literary scene, her works criminally under-recognised today, her name little known. When I look at the Comyns’ novels on my bookshelves, they are from a clutch of independent presses – Virago, Daunt, Turnpike, New York Books – with no particular home.

Gothic, macabre, witty and unpredictable, novels like hers are the reason you go into a secondhand bookshop and shelf-dive; they are the dream outcome of paying £2 for an obscure book because you like the weird title. Of course, we’re used to hearing about neglected literary gems, salvaged from obscurity to be republished in shiny new editions. Yet Comyns has been discovered, lost, rediscovered and lost again, repeatedly. A new biography released this month, by Avril Horner, a specialist in women writers and the gothic, may help her finally stick. But even that book was in the balance – Barbara Comyns: A Savage Innocence took three years to find a publisher.

“My sense was she was too risky, because she wasn’t well known,” Horner tells me. “Yet as a writer she has the extraordinary capacity to bring you up short. I don’t see it in any other British writer before her – this ability to shift in tone from something very melancholy to a sudden joke, and vice versa.”

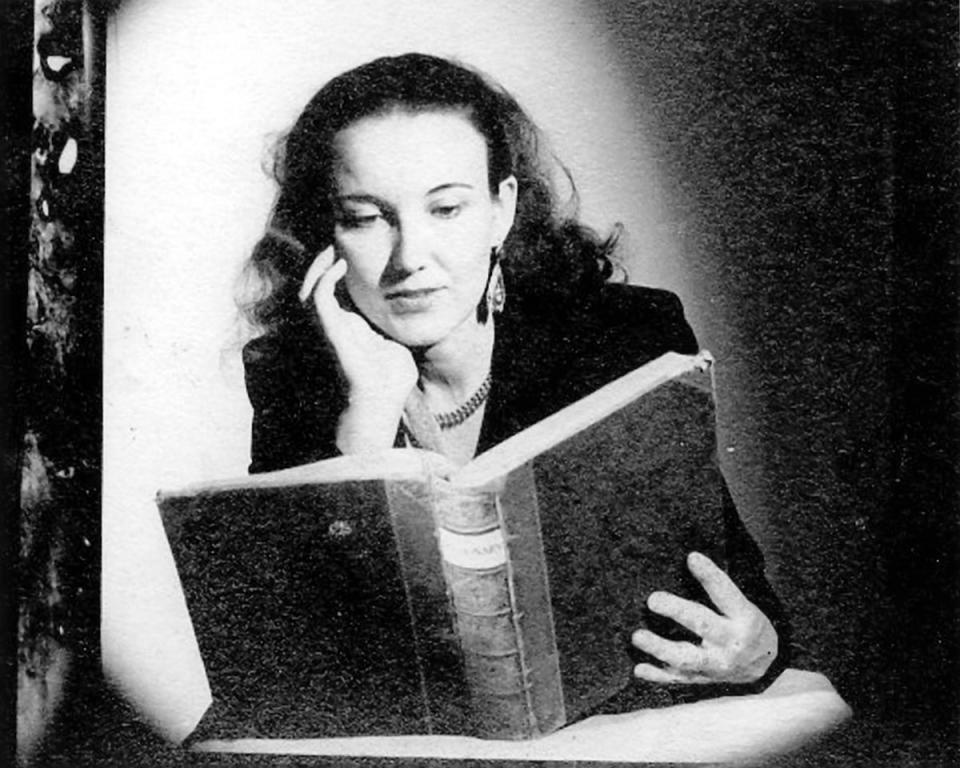

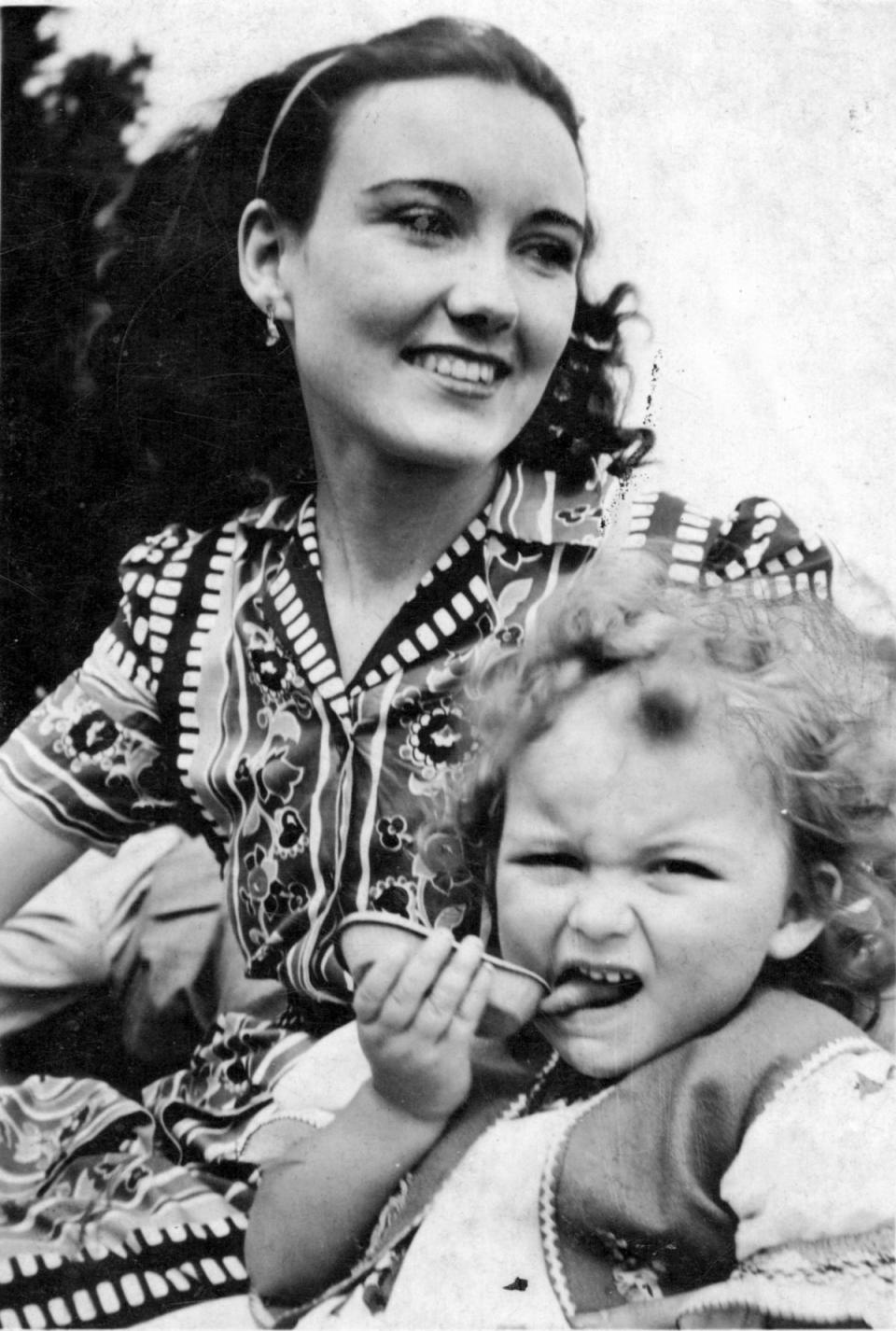

Barbara Comyns was born in 1907 in the sleepy village of Bidford-on-Avon. Before she was a novelist, she was, variously, a painter, sculptor, poodle breeder, piano restorer, artist’s model, and housekeeper. She grew up in a crumbling manor surrounded by a river, her father a tyrannical brewer, her mother removed, and she had the kind of semi-feral middle-class childhood that seems to have coloured her approach to living: resilient, self-sufficient, always slightly wild. All her life, she was surrounded by animals, from the peacock that stalked the lawns of her first home to the newt she carried around as a young woman.

Her early life with John Pemberton, husband number one (feckless) and father to son Julian, was marked by poverty. Later, she had a messy affair with married art critic Rupert Lee with whom she had her second child, Caroline. Life with her second husband, Richard Comyns Carr (gentle, devoted), was happier, with many years spent in Spain – but he was later to lose his job with MI6, probably because he was a friend of notorious British spy Kim Philby.

Having started writing about her unusual upbringing in order to amuse her children, Comyns turned these unselfconscious vignettes into her first book, the autobiographical Sisters by a River, which was published to acclaim – and some bewilderment. “Pray form your own opinion of this unique work,” wrote Elizabeth Bowen. That comment captured the general consensus towards her work throughout her life: many critics were captivated, some were confused, and some were both at the same time.

The best starting point for curious readers is The Vet’s Daughter, which tells the story of a young woman in south London who discovers she can levitate when horrible things happen, like a bohemian Matilda Wormwood or a genteel Carrie White. With its dark atmosphere, grotesque characters and handbrake-turn twist, it’s a crash course in Comyns, was made into a musical in 1978, and has seen various – failed – attempts to turn it into a TV drama (please BBC, it would be the perfect 90-minute Christmas special). Her work falls into two camps – realist domestic stories and gothic tales – but among their frank prose and sharp wit, they explore dark subjects, including abortion, sexual assault, racism, motherhood, and varying degrees of mental disintegration.

Perhaps she fell away periodically because these topics were too much for readers at the time, or dealt with too bluntly. In practical terms, it was likely because her writing was well received but never a major seller. Not until she was rediscovered by Carmen Callil at feminist publisher Virago in the 1980s, where her work was republished as part of its Modern Classics lists, did her work sell more than modestly. Prompted by a new appetite for her work, that decade she published the novels Mr Fox and The House of Dolls – both presented as “new” Comyns novels, but actually plucked from the bottom of drawers, having been rejected by publishers a couple of decades earlier.

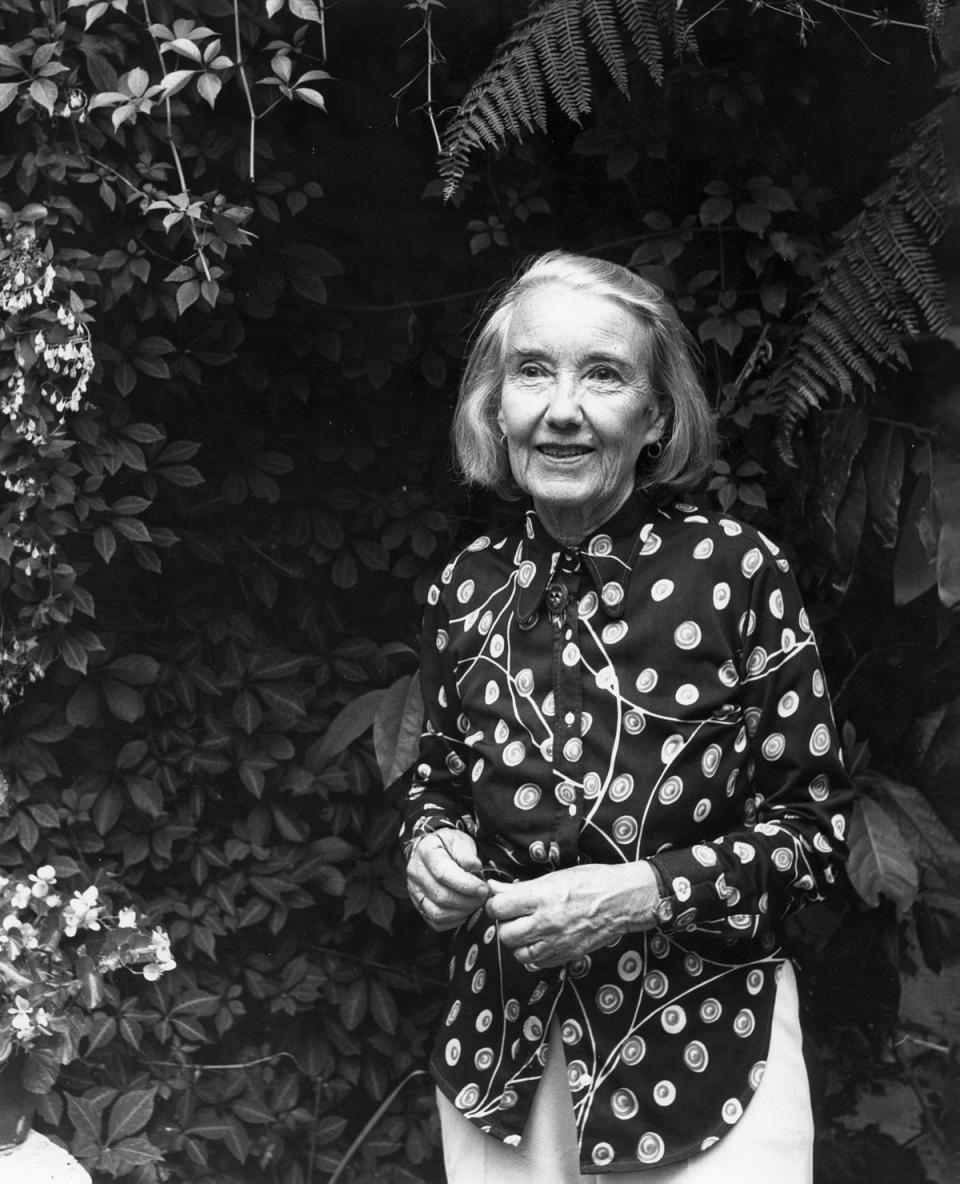

Comyns knew that her readership hung in the balance as she went in and out of fashion. After another rejection letter for the unpublished-to-this-day Waiting in 1979, she told her agent that she’d never write again (although she did – her great final novel The Juniper Tree, published in 1985) and speculated that perhaps one day she’d see a revival. “Remember Barbara Pym!”

Horner first became interested in Comyns when she and a colleague were asked to contribute to an academic journal about the female gothic, and her colleague suggested that rather than focusing on Mary Shelley and the usual suspects, they look at Comyns. The more Horner read, the more intrigued she became – and promised herself that when she had time, she’d write more about Comyns. It wasn’t until she retired that she could write the biography she’d long hoped to author. It’s a book that will delight Comyns devotees. It brings to life many of the incidents that clearly informed the novels, and reveals the depth of feeling lurking beneath that clear, measured prose. Comyns’s naive, child-like heroines have led to some categorising her work as closer to “outsider art”, but Horner found that, “behind all those naive young women is a very knowledgeable author, drawing on her own experience in a very thoughtful, knowing way.”

But uncovering the facts of her life wasn’t easy. When Horner went to visit Comyns’ granddaughter Nuria Leighton, she discovered Comyns’ papers in disarray. “They were in no order, which Nuria freely admits,” Horner tells me. “She doesn’t want to part with any of them, but they were in carrier bags, boxes, things stuffed in envelopes, under the bed.” But nestled within them were treasures: a correspondence with Graham Greene, for example, that showed the author to have been a lifelong champion of Comyns’ work.

I don’t see it in any other British writer before her – this ability to shift in tone from something very melancholy to a sudden joke

Horner’s book is an important intervention, ensuring Barbara Comyns’ name is not forgotten. But it’s also a reminder that writers’ legacies need careful stewarding and are never guaranteed. Her book is published in the same month as Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s “lost” novel Until August, the latter feted as one of the literary events of the year. Yet that unpublished Comyns novel Waiting – about an old people’s home where the residents are “waiting to die but things keep happening”, where they “feel even more intensely than when they were young” – really is lost. Some of her books remain out of print (her ickily titled The Skin Chairs is “almost impossible to get hold of unless you pay a lot of money,” Horner says.)

Although Comyns has been compared to Nancy Mitford, Angela Carter and Jean Rhys, and called “Beryl Bainbridge on acid”, she remains impossible to categorise. “She’ll be writing in a rather comical way and then suddenly – bang – you’re in a different emotional world,” says Horner. “She manages to harness the uncanny in a new way for women writers.”

She’s also, Horner admits, “like marmite”. And she’s right – I’ve occasionally felt self-conscious about recommending her too fervidly to the uninitiated, given the grand guignol scenes of horror in some of her works (a lot of villagers sensationally kill themselves in Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead). I struggle with the deliberate, affected spelling mistakes in Sisters by the River, and I can’t handle her gruesome descriptions of animal deaths.

But part of Comyns’ brilliance is that she draws from a vast palette of difficult, sometimes unbearable experiences, in a way that feels before her time. When she published Our Spoons Came From Woolworths, she included the disclaimer, “The only things that are true in this story are the wedding, chapters 10, 11 and 12, and the poverty.” The chapters she mentions contain some of the most visceral, horrifying descriptions of childbirth that you will read.

A Savage Innocence is prefaced with a quote from Mr Fox: “In the back of my mind I was always sure that wonderful things were waiting for me, but I’d got to get through a lot of horrors first.” It’s poignantly appropriate. Certainly Horner’s biography reveals the pain and frustration she felt at her years in the wilderness, and made me sad for all the Comyns books we might have got had she been better championed in her later career. Horner’s descriptions of her final years, widowed and succumbing to dementia, are hard to read. Having previously worked on an edition of the letters of Iris Murdoch, who was also struck by dementia in later life, as indeed was Marquez, the biographer believes it is always an ethical decision as to how much material from that time should be used. “Reading her scribbled bits of paper – she wasn’t the same woman that she was. I found it very sad,” Horner says.

When Comyns died in 1992, the writer Ursula Holden’s obituary for The Independent called her “a true original… her death marks a loss to English writing”. Her family marked her death, Horner reveals, by each pouring a gin and tonic on her grave, something they repeat whenever they find themselves back at the churchyard where she is buried. A true original indeed – strange and beguiling to the end.

‘Barbara Comyns: A Savage Innocence’ is published by Manchester University Press on 19 March