Why Alice Stewart's Death Hit Washington Especially Hard

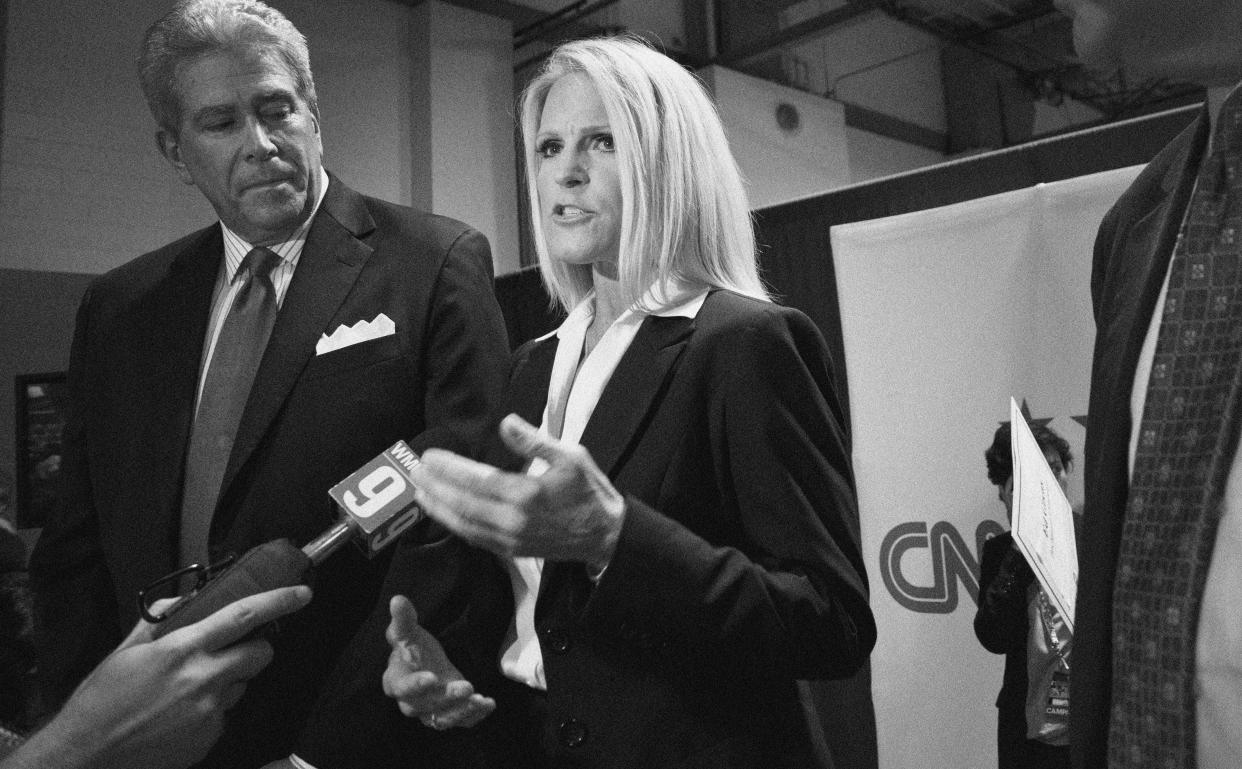

Alice Stewart speaks for Michele Bachman in the spin room after The New Hampshire Republican Presidential Debate at Saint Anselm College in Manchester, NH in 2012. Credit - James Leynse—Corbis/Getty Images

This article is part of The D.C. Brief, TIME’s politics newsletter. Sign up here to get stories like this sent to your inbox.

Alice Stewart represented a modern master class in how to hold sincere beliefs without surrender or skirmish. The Republican strategist respected the cynics and critics across the table enough to talk, not sneer. As fierce as could be as an advocate and as shrewd as any as a tactician, she also had the qualities that have become all too rare in politics: she was unfailingly kind, unyieldingly generous, and hopelessly decent, even when it was obvious that she and her sparring partner were never going to see things the same way.

As Washington pauses to remember Stewart, who died unexpectedly Saturday at age 58, her professional acumen is the most noted element in the tributes, but for those of us who have covered her campaigns, the loss means so much more. Stewart was, simply put, one of the best in the business who could work both the journalism side of a story and the operative one with the same rigor and honesty. She was always on, but never insincere.

A longtime distance runner and CNN commentator, Stewart may have been the most credible conservative communicator of an era. Where others in her orbit chased memes and viral moments, Stewart advised candidates and causes to work with facts and proven case studies. Where populist outrage fueled so much of the Republican landscape dating back to the 1994 Republican Revolution, Stewart gently nudged the GOP to appeal to the apolitical middle class voters that actually decide most elections.

Consider the remarkable record she built in presidential politics after a successful career as a television producer, reporter, and anchor. In 2008, Stewart guided a lesser-known Southern Governor from second-thought favorite of the homeschooler movement to a serious contender for the White House. In the 2012 cycle, she took a sharp-edged Tea Party favorite and helped her win—admittedly at tremendous cost to donors and the institution itself—an early test vote in Iowa. After that bid blew apart, Stewart joined up with the most credible conservative left in that 2012 primary, helping an ex-Senator who lost his re-election by 17 points emerge as a potential frontrunner heading into 2016. And once it became clear that Stewart’s Republican Party had misjudged the threat from a New York reality star in 2016, she pivoted from her first major boss in politics to a burn-it-down troublemaker from Texas as an effort to make sure true conservative viewpoints were a part of the debate.

And through it all—the long days, the tough news cycles, the unlikely odds, and problematic candidacies themselves—she kept a calm demeanor that is a rarity in campaign orbits. In a high-pressure world of presidential campaigns, her arrival brought some measure of stability to the traveling roadshows and a professionalism to exhausted and snippy candidates. Where most aides somewhere along the way came to believe that screaming would yield solutions for tricky moments and bullying could soften bad stories, Stewart would start more gently—often with a text message or email asking when a good time to chat might be found—and then proceed to methodically outline the problems she had with a story, and ask to maybe include more perspectives the next time. She was tough, but never toxic. Sure, she was playing the long game, but she also really liked her role as a frontline liaison to some of the biggest newsrooms in America.

While she never shied from the hard-right animators of the Republican Party’s activist class, she also preached that politics is a game of addition, and if you’re not adding new voters to a cause, you’re losing. No one would ever credibly call her a “squish,” but she didn’t pick fights unless there was a clearly defined victory and a path to get there. Feelings were no substitute for field position. Orthodoxy didn’t change the vote tallies. Inside campaigns, even her nominal bosses often turned to her as the last voice in a room to weigh in; if Stewart said something was a bad idea that would play poorly with the press—and thus the broader audience—then it might be worth a second pass through that SlideDeck.

So when news broke about Stewart, the political press corps, the communications veterans who worked alongside her, and the next generation of operatives she coached all took a beat.

Consider this one episode from the 2012 campaign. Even by Iowa-in-December standards, that week leading into Christmas of 2011 was especially harsh. Wind gusts in some parts of the state hit 60 miles per hour. Visibility was garbage, a foot of snow was falling on highways and back roads, and it was almost impossible to make readers—or editors—care about what we were seeing.

Put as plain as possible: the campaign reporters tracking Rep. Michele Bachmann’s 10-day, 99-county tour of Iowa were pretty glum. Bachmann’s frazzled staffers and volunteers weren’t much better, seemingly rushing between photo-ops that lasted, in some cases, fewer than 10 minutes for 100 people. It all seemed pointless, and those are the moments when group-think can doom a candidate. But one effort at optimism stood out to those of us chasing Bachmann, a one-time rising star in the Tea Party-fueled GOP but someone whose sizzle seemed to simmer then slump the further she got from her first-place finish in the Iowa Straw Poll months earlier.

Stewart saw what was happening and knew a morale problem could become a self-fulfilling prophecy. She watched it on the juggernaut campaign of Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee that flamed out four years earlier as the last dollars burned with the jet fuel they couldn’t afford. Stewart turned to the most humanizing accessory available to any campaign: a dog. Her Shih Tzu named Samantha, short-handed to Sam, joined the bus tour and provided what today we’d call therapy-dog services to the journalists, staffers, volunteers, and even Bachmann family members who packed into crowded diners and country stores to watch the candidate repeat the same script over and over and over again for a videographer. It made for long days with little new material to hang a daily story on.

Yet, when Stewart fed reporters the daily schedule and talking points, she was often holding the pup in her arms. Sam herself wasn’t good for quotes, but it was a helpful reminder that Stewart, like the reporters, was a human on the other side of the campaign-industrial complex. As much as it was easy and convenient to vent about a campaign, a real-life person is a lot harder to hold in contempt, especially when the person standing there is a model of empathy.

Of course, a pup alone cannot change the political forces in Iowa—or nationally, for that matter. But it was a moment of solid instinct that took the edge off a whole lot of reporters who were Bachmann’s best hope to get her message out. Even as Bachmann’s security team scuffled with journalists who got too close or seemed like threats to the lone woman in the race, Stewart and her dog were able to neutralize the high-tension moments.

And that was Stewart’s super power: in a powderkeg environment, she not only brought calm to almost any situation, she did it through her authenticity, even in the most manufactured of environments. A consummate professional, she deserved every ounce of goodwill that reporters had for her, every belief that she was doing her best to be a straight-shooter even in those cases when complete honesty might not have been the best option for her candidate or cause.

On the road, there were moments she saved many a journalist with just simple acts of decency. When she could, she’d order extra boxed lunches in case we had missed a meal or two or three trying to keep up with her candidate. On the days when one of her candidates was able to pull right up to a door of an auditorium and park—while the rest of us dare not risk a tow with such VIP behavior—Stewart had her tape-recorder running and a full audio recording available in full to anyone who was running late. And here’s the thing that stands out: most of us had zero reasons to question the veracity of those files; Stewart was, at her core, one of us and as committed to the facts as ever. Plus, she understood that cutting corners and hoping no one would find out was a recipe for disaster.

Outside of White House bids, Stewart was a go-to crisis manager for problem House and Senate candidates, ghost-writing strategy memos to bail out the scandal du jour or smack tough love into a spiraling campaign. She would occasionally step in when relations between campaign HQs and the national political reporters turned testy. She was an unsung fixer on second-tier candidates and the face of the first-tier ones when the consequences were as high as they come for her fellow conservatives.

On a selfish level, I always enjoyed my conversations—in church lobbies, in hotel parking lots, on friends’ rooftops—with Stewart because, inevitably, I’d learn something new or discover a slightly fresher way of looking at the situation. She was a partisan, but not a blind one. Stewart worked against Trump’s nomination during the primary as Senator Ted Cruz’s top communicator but never fell into the NeverTrump category after Cruz faded. She voted for Trump when he was on the ballot but told anyone who asked that she didn’t lose her sense of right or wrong, let alone her hard-forged common sense, to do so. She just picked between the options available and couldn’t find common ground with Hillary Clinton or Joe Biden. And, in the time between her near-constant hits on CNN and her work teaching a new generation of conservatives—especially women—how to talk politics, she often channeled Huckabee’s all-too-common recitation that she was conservative but not angry about it. It was a nice antidote to the Trump era, and one whose exit will leave our politics lacking.

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the D.C. Brief newsletter.

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com.