'Their way has failed,' FSIN chief says in wake of child welfare law ruling at Supreme Court

Indigenous leaders in Saskatchewan are celebrating after the Supreme Court of Canada ruled Bill C-92, which affirms that Indigenous nations have jurisdiction over child and family services, and outlines national minimum standards of care, is constitutional.

"We will be able to protect our children through our own rights, through our own laws and also our laws will paramount provincial laws, which is extremely important moving forward," said Aly Bear, the second vice-chief of the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN) at a press conference on Friday.

Bill C-92 became law in 2019. Quebec challenged the law on jurisdictional grounds, but the court unanimously upheld it.

"It's a very important historic ruling and we're very happy. I know a lot of people across this country from one end to the other are very pleased with the decision," said David Pratt, second vice-chief of FSIN.

Aly Bear, centre, is the second vice-chief of the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations. (Liam O'Connor/CBC)

Glen McCallum, president of Métis Nation–Saskatchewan, said in a news release that it was a great day for Métis people in the province.

"Today's monumental decision by the Supreme Court is a confirmation of the work our Métis government has been doing for citizens in protecting and strengthening our families to preserve Métis identity, culture, values and language for future generations," said McCallum.

'Their way has failed for several decades': FSIN chief

The FSIN held a news conference Friday to celebrate the decision, but also send a clear message to provincial governments.

Pratt denounced Quebec's decision to challenge Bill C-92 instead of choosing to work with First Nations.

"Our message today to the provinces and territories is to step aside and let First Nations take over, and let us do the work that needs to be done with our children and with our families," said Pratt.

FSIN Chief Bobby Cameron, centre, sits alongside second vice-chief Aly Bear, left, first vice-chief David Pratt at Friday's news conference. (Liam O'Connor/CBC)

FSIN Chief Bobby Cameron shared similar sentiments.

"Their way has failed for several decades," said Cameron.

"From the residential school system to the Sixties Scoop, to even now, in the current child welfare system, their way has failed."

Implementation still work in progress

In 2021, Cowessess First Nation inked the first deal with the federal and provincial governments to take control of decision-making over its children and youth.

Cowessess Chief Erica Beaudin also celebrated the monumental decision coming down from the Supreme Court Friday.

"I can't say anything except that this is a good news day, a great news day," said Beaudin over a Zoom call.

"Not only for us as Indigenous peoples, but for all Canadians, because it recognizes the diversity and the original peoples of the land and how we can all move forward together."

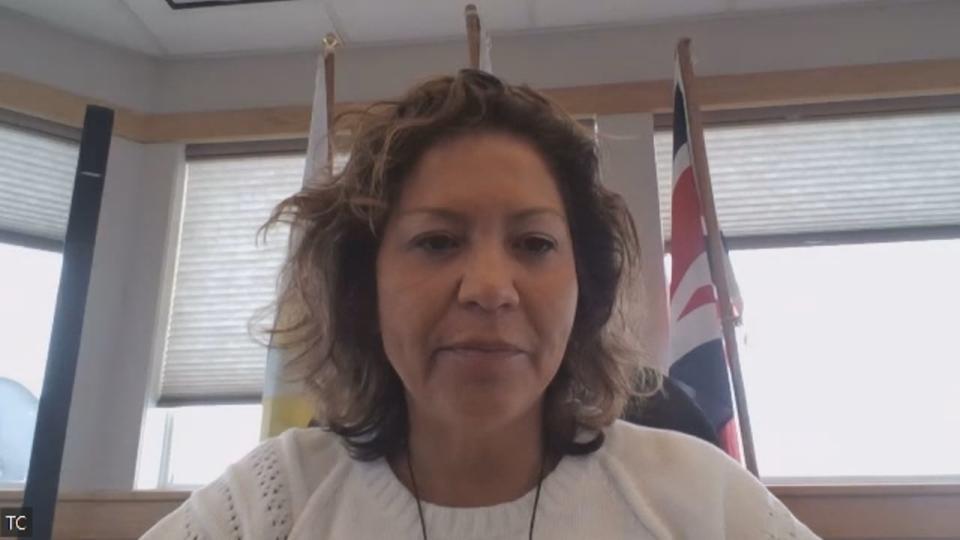

Erica Beaudin, chief of Cowessess First Nation, said the Supreme Court's decision was great news. (Liam O'Connor/CBC)

Beaudin said the First Nation has been working on implementing its own child welfare system, but that it's complex and requires lots of care and money.

"We do know that the costs are much more significant in order to even get to the level, the bar that the provincial government is funded at, in order to provide care for children and families, especially those with special or extraordinary needs," said Beaudin.

Beaudin said that as the first First Nation to do this out of gate, Cowessess has learned lessons that will help other First Nations as they begin to implement their own welfare systems.

"We are very determined, we are very committed to working out the kinks and we are not alone."