Victoria is raising minimum rental standards – it’s good news for tenants and the environment

Following the lead of countries like New Zealand and the United Kingdom, Australian states and territories are moving slowly towards improving the basic quality and performance of rental housing.

Victoria is leading the way in Australia. The state government this week proposed new minimum requirements for rental properties and rooming or boarding houses. These changes would be phased in from October 2025.

The new standards will greatly improve the quality and comfort of rental housing. They will also make it cheaper to live in.

It’s the most far-reaching response by any Australian government to the huge and well-documented problems of affordability and poor conditions in our rental housing.

Why are better standards needed?

About a third of Australian households live in rental housing. They include many of our most disadvantaged and vulnerable households.

The sector also has some of our poorest-quality housing. Many rental properties are energy-inefficient and poorly maintained.

The proposed standards are likely to help households by:

reducing energy bills to help manage the cost of living

improving health and wellbeing by providing more stable and comfortable temperatures in the home and reducing damp and mould

reducing environmental impacts by cutting energy use and moving away from gas appliances.

This government intervention is a step in the right direction. Market-based approaches to improving the quality and performance of private rental properties are failing to deliver.

State and local governments have increased financial support for retrofitting housing to improve its performance. However, research has found uptake by landlords has been limited.

Minimum standards have been successfully introduced overseas. In the UK, for example, landlords must ensure their properties achieve at least a level E energy performance certificate (A is best). The aim is to lift the bottom of the market to a new minimum standard over time.

What is being proposed?

This table shows the key changes proposed in Victoria.

A landlord would only be required to make these changes to the property at the start of a new lease or at the end of an appliance’s lifespan. This will help spread the costs over time. But it also means tenants might not see immediate improvements come October 2025.

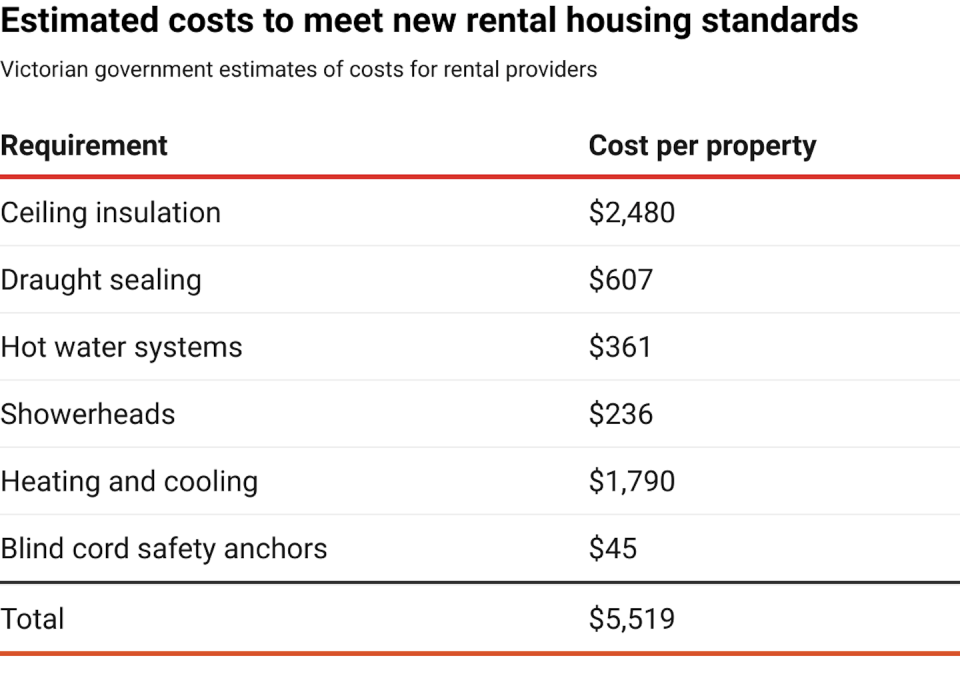

The government estimates the average extra cost of delivering all requirements at A$5,519 per property. Of course, the cost impact will vary. Some homes will already meet some or all of the new standards.

Landlords who want to make improvements before October 2025 could get Victorian Energy Upgrade subsidies. But these are only available for voluntary activities. This financial support will not be available for landlords once the minimum standards become mandatory.

This table shows the estimated extra costs of the new standards compared to business as usual.

Wait, weren’t minimum standards already in place?

Victoria introduced minimum standards for rental properties in 2021. These include:

a fixed heater (not portable) in good working order in the main living area

a stovetop in good working order with two or more burners

inside rooms, corridors and hallways have access to light to make the areas functional

all rooms free from mould and damp caused by or related to the building structure

windows in rooms likely to be used as bedrooms or living areas fitted with curtains or blinds that can be closed, block light and provide privacy.

The aim of the proposed new changes is not just to deliver basic rental housing, but housing that is safe, comfortable and energy-efficient.

What challenges will these changes bring?

Potential challenges include:

many landlords are already financially stretched and may pass on improvement costs to tenants or exit the market, but research indicates the likely impact of these responses is low

changes will supercharge the retrofit industry, so strict governance will be needed to avoid issues with “cowboy” operators, as happened with schemes such as the Home Insulation Program – the so-called “pink batts” scheme

labour shortages across the construction industry mean more workers will have to be found to deliver these upgrades

we don’t yet know what the processes will be for checking compliance and providing recourse if upgrades fall short of requirements

tenants may hesitate to assert their rights because affordable rental housing is so hard to find

safeguards will be needed to protect tenants from rent increases

there is a risk of gentrification if landlords decide to comprehensively retrofit and renovate homes.

Finally, even though this is an important milestone, more needs to be done. For example, having only one heater in the living room means tenants will need to use portable electric heaters in bedrooms or run the risk of mould developing. Similarly, having only one air conditioner in the living room means people will suffer during hot summer nights unless they sleep in that room.

Renters in the rest of Australia are missing out on these important protections. Progress is urgently needed across the country if we, as a nation, are going to ensure renters have equal access to safe, cost-efficient, resilient and low-emission homes.

This article is republished from The Conversation. It was written by: Trivess Moore, RMIT University; Emma Baker, University of Adelaide; Lyrian Daniel, University of South Australia, and Nicola Willand, RMIT University

Read more:

Too many renters swelter through summer. Efficient cooling should be the law for rental homes

What if I discover mould after I move into a rental property? What are my rights?

Do tenancy reforms to protect renters cause landlords to exit the market? No, but maybe they should

Trivess Moore has received funding from various organisations including the Australian Research Council (ARC), Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), Victorian government and various industry partners. He is a trustee of the Fuel Poverty Research Network.

Emma Baker receives funding from the ARC, AHURI and the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). She is a board member of Habitat for Humanity SA.

Lyrian Daniel receives funding from the ARC, NHMRC and AHURI.

Nicola Willand receives funding for research from various organisations, including the ARC, the Victorian state government, the Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation, the Future Fuels Collaborative Research Centre and the NHMRC. She is a trustee of the Fuel Poverty Research Network charity and affiliated with the Australian Institute of Architects.