Teen says leaving school for classes at mental health treatment centre was necessary path

Lennon Mulcaster said it was difficult to go through life because of what was expected of them.

The 17-year-old from Windsor, Ont., suffers from social anxiety and depression — causing them to struggle with academics since middle school, they said.

"I had basically completely shut down, and it was very difficult," said Mulcaster. "My parents tried to be supportive."

Mulcaster and their parents had them transferred to Maryvale, a local mental health treatment centre for students between grades eight and 12.

"There's a lot of pressure to choose career paths, especially now because I'm graduating soon. With my struggle in mental health, in schools, there's not a lot of support … and with traditional classrooms, there's like 20, 30 students in there. So teachers can't focus on you."

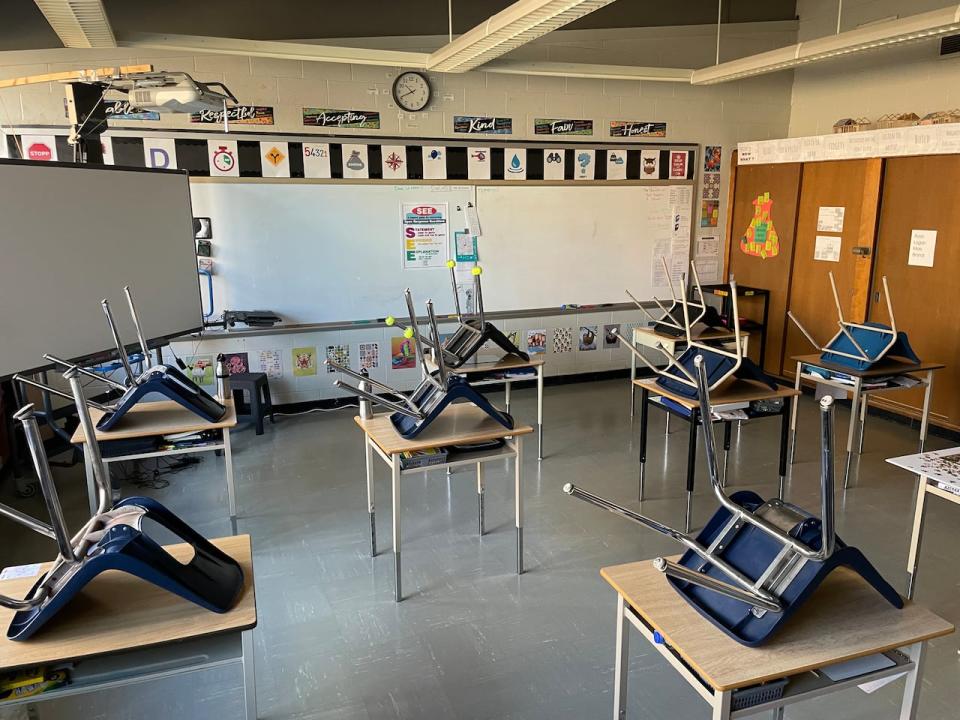

The Maryvale treatment centre incorporates classroom setting learning for adolescents experiencing emotional, psychological and mental distress. (Amy Dodge/CBC)

Roughly 10 years ago, Maryvale moved away from a residency model for dealing with youth addictions and mental health issues. Now, the facility offers daytime programming — mainly in a school classroom-type setting.

As previously reported by CBC News, some youth with complex special needs, in the care of the Windsor-Essex Children's Aid Society (WECAS), are ending up lodged in hotels. WECAS executive director Derrick Drouillard said parents and caregivers were "exhausted" trying to find the right supports and that it's a crisis across Ontario.

"Basically, the goal is just to get you into that school setting. It doesn't matter if you're doing well."

According to Mulcaster, their life has "definitely improved" since beginning at the treatment centre.

They said there's "renewed hope" with an overall better quality of life — with more exposure to social interactions.

"I feel a lot more supported and more that people care about me, and not swept under the rug because you're not showing up."

Mulcaster spoke with Windsor Morning host Amy Dodge at Maryvale. (CBC)

Before entering the programs, Mulcaster said they were so depressed they couldn't even leave their room.

"Now I'm picturing myself in the future, having a job and having a family and having my own house, which will still probably be really difficult in this economy, but there's hope."

Mulcaster said they're looking at getting their high school credits, graduating and then possibly going to college.

"With the exposure and having that support … I'm able to meet people who have similar experiences to me. I'm able to make a lot deeper friendships and connections that are really meaningful to me."

Windsor's Karen Wilson previously told CBC News her son — who has an intellectual disability — would be in jail today if it wasn't for programs such as Maryvale's.

Wilson now helps other parents navigate similar situations.

Laura Crowley-Hall, who oversees day treatment at Maryvale, said students come to them with a variety of mental health challenges or needs.

"It could be they're having issues in their community school," she said. "There could be issues in their home, in their community. A lot of our students have various mental health diagnoses, anywhere from anxiety, depression, OCD, self-harm, coping, poor self-regulation."

It's teaching self-regulation reset buttons, said Crowley-Hall. Their goal is not to end up keep students in their care for the duration of their secondary school career.

Laura Crowley-Hall is the director of day treatment at Maryvale in Windsor, Ont. (Amy Dodge/CBC)

"We always want them to build skills and then go back into their community school, whichever setting that might be.

Maryvale opened in 1929, accepting wayward young women. It began to introduce boys in the mid 1950s. Years later, at its peak, it had six residential cottages, with roughly seven teens staying in each one.

Treatment centre not prioritizing return to housing

The centre's executive director doesn't think bringing back the residential program is a top priority.

Andrew Ward said their daytime programming allows them to serve more families and keep kids in their homes.

"We are a treatment service provider and not a housing provider," he said.

"We will serve in collaboration wherever the need is greatest, and so we want to provide mental-health services first, before anything else."

Maryvale primarily serves young people aged 13 to 17 and their families. These teens may be experiencing a range of mental health issues. (Amy Dodge/CBC)

Ward said working in collaboration with community partners such as hospitals and a regional children's centre is key to meeting the needs in the area.

"It wouldn't be our priority to be a residential treatment provider. It would be to be a treatment service provider first. We will stand in the gap, and address the needs of our region, but we would not prioritize one service and not the other."