Sue me, if you can. How laws that prevent directors being sued make firms less likely to recall potentially dangerous products

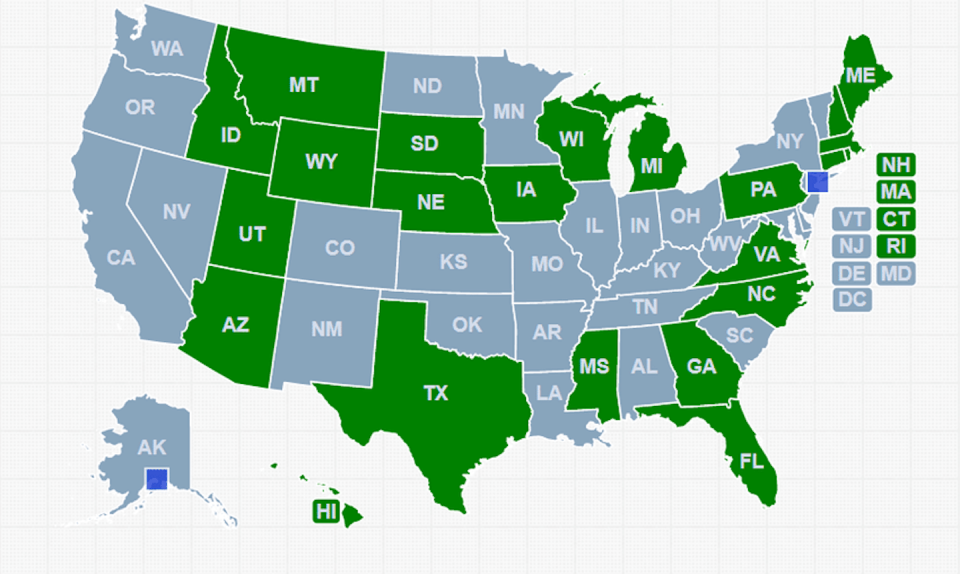

About half the states in the United States have introduced so-called universal demand laws that make it harder for aggrieved shareholders to sue company directors and hold managers personally liable for decisions that have harmed the company.

One such lawsuit by Boeing shareholders resulted in current and former directors of the airline agreeing to pay it US$225 million over claims they had failed to properly oversee matters related to the safety of the relatively new 737 MAX after crashes in 2018 and 2019 that killed 346 people.

The payment went to the company rather than the shareholders who sued, allowing them to benefit indirectly along with other shareholders.

Boeing is incorporated in Delaware. Had it instead been incorporated in one of the 25 or so states with “universal demand” laws, the lawsuit would have been harder to get off the ground.

Universal demand laws make it harder to sue directors

In an attempt to work out the way in which the spread of these laws has changed the behaviour of directors and managers, we took advantage of their staged introduction, which began with the state of Georgia in 1989.

Our findings, analysing over 30 years of data from thousands of firms, were published this year in the Journal of Marketing. They point to an alarming unintended consequence of universal demand laws: a reduced willingness of firms to recall potentially hazardous products.

Firms incorporated in states that have adopted these laws are on average about 30% less likely to announce product recalls than firms incorporated in states without these rules.

We can find nothing else – neither improvements in product quality nor improvements in operational processes – that explains what we have found.

We have also observed a delay in the timing of the product recalls that firms in these states do issue.

On average, firms incorporated in states that have adopted universal demand laws wait about 50% longer before announcing recalls than firms in states that have not.

It means customers of firms incorporated in these states are exposed to potentially dangerous products for longer than customers of other firms.

In Australia and the UK too

Although our research uses data from the United States, its insights are universal.

Australia and the United Kingdom are two countries in which legal precedents make it hard for shareholders to sue directors and officers of companies. This means the rules are more like those of the US states that have adopted universal demand laws than those that have not.

Our findings suggest that, by shielding Australian and UK executives from personal liability, the law in these countries makes product recalls less likely than it could be. In turn, that makes the continued use of potentially dangerous products more likely.

In the absence of effective legal sanctions in these countries and in the US states that have adopted universal demand laws, it is up to companies themselves to make it harder for their executives to cut corners.

Firms need to help themselves

Our research has identified two things that can help. Both seem to have an effect in the US states that make it hard for shareholders to sue directors.

One is oversight by institutional investors. As shareholders with large financial stakes, they are motivated to monitor executives in order to protect their long-term interests in a way in which company officials might not be.

We found the effect on product recalls of being incorporated in a state with universal demand laws was 10% less strong in firms with a high proportion of institutional ownership.

It’s an argument for firms to try to build up the proportion of their shares owned by long-term institutional investors.

Customer advocates can make a difference

The other thing that helps is a customer-focused culture. Such a culture is often denoted by the appointment of a chief marketing officer to the board of directors or the appointment of a consumer advocate.

We used text analysis of financial disclosures to develop a metric for the extent to which public companies were customer-focused.

We found the effect on product recalls of being in a state with universal demand laws was 11% less strong in companies that were highly customer-focused.

Without a strong customer-focused culture or pressure from investors or laws that focus the minds of executives, we have found firms are more likely to take shortcuts that will hurt both their customers and their enduring reputations.

For example, in 2021 the execise equipment company Peloton finally announced a recall of its treadmills after weeks of saying there was “no reason” to stop using them. Its share price fell 15.8%.

Dozens of customers had been injured and one child was reported to have died.

Peloton’s chief executive, John Foley, was forced to admit: “Peloton made a mistake in our initial response.” It cost it US$165 million in sales.

This article is republished from The Conversation. It was written by: Arvid O. I. Hoffmann, University of Adelaide; Chee Seng Cheong, University of Adelaide, and Ralf Zurbruegg, University of Adelaide

Read more:

What’s the job of a company chair? South Africa’s rules aren’t clear and need fixing

Sugar in baby food: why Nestlé needs to be held to account in Africa

Greenwashing claims on trial: should NZ ban fossil fuel advertising?

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.