Polaroids of the everyday and portraits of the rich and famous: you should know the compulsive photography of Andy Warhol

Review: Andy Warhol and Photography: A Social Media, Art Gallery of South Australia.

Andy Warhol is well known for his slick pop art imagery which fetches staggering amounts at auction. His Shot Sage Blue Marilyn sold in 2022 for US$195 million.

But there is a little-explored side to Warhol-the-photographer, whom curator Julie Robinson explores in a brilliant new exhibition.

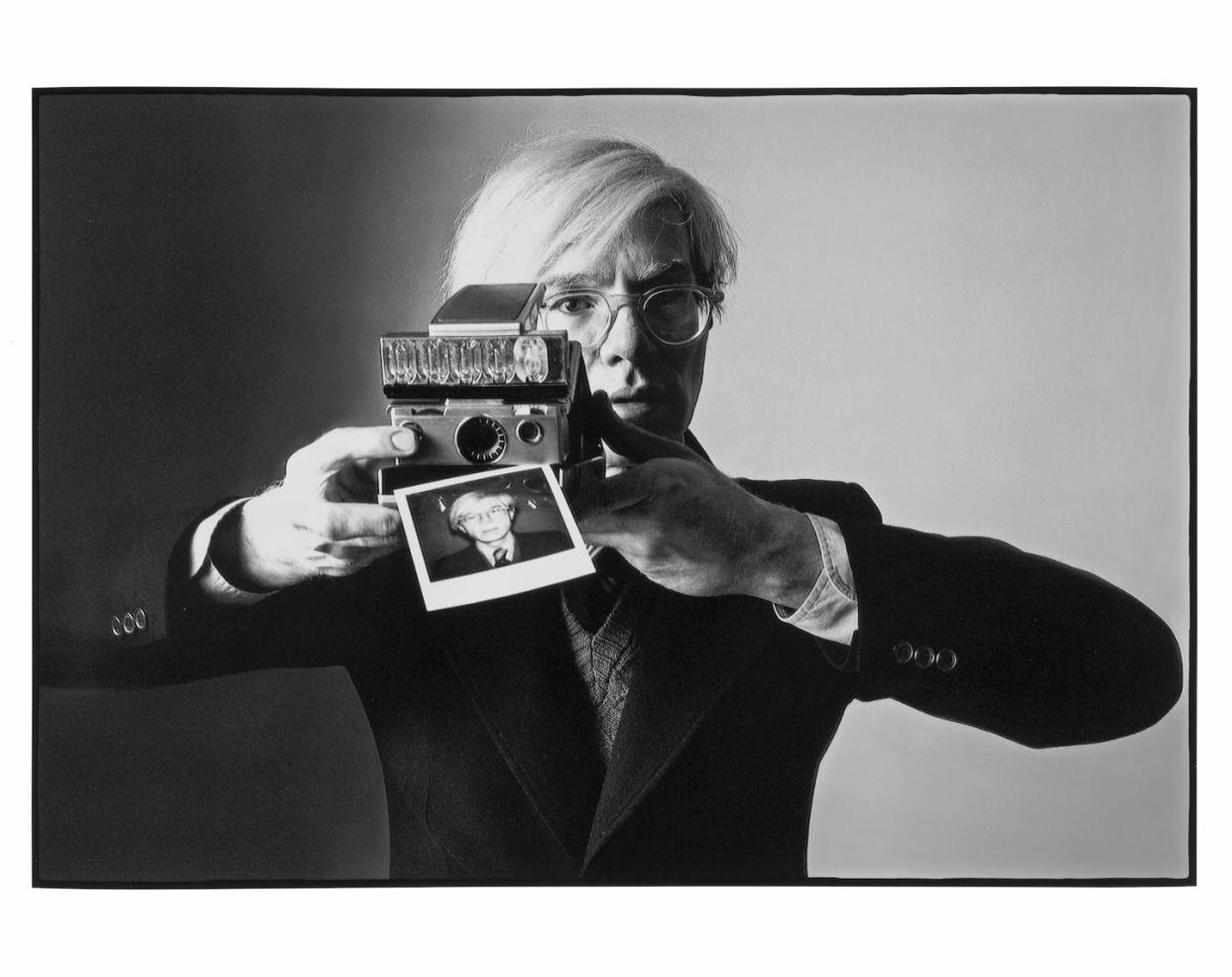

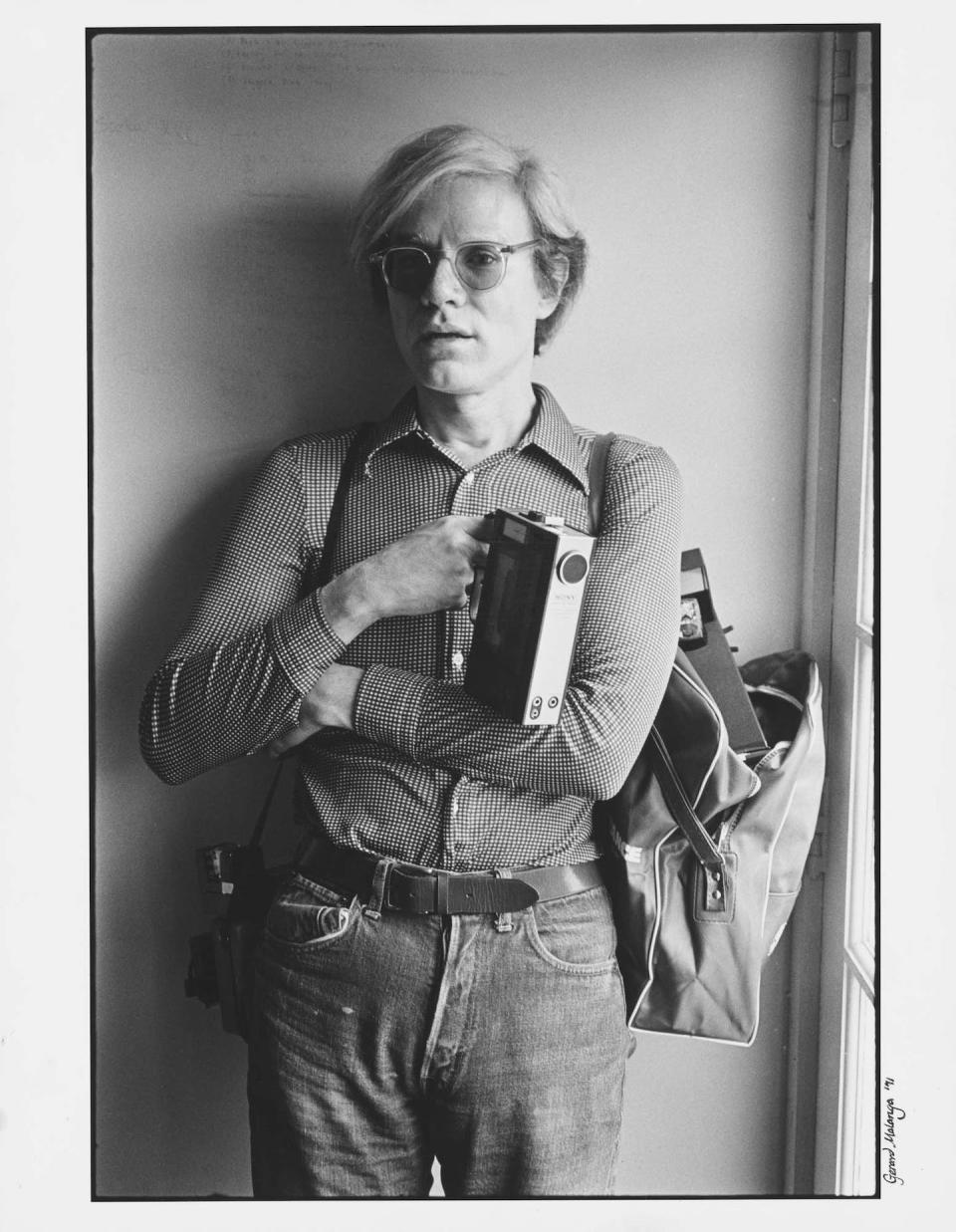

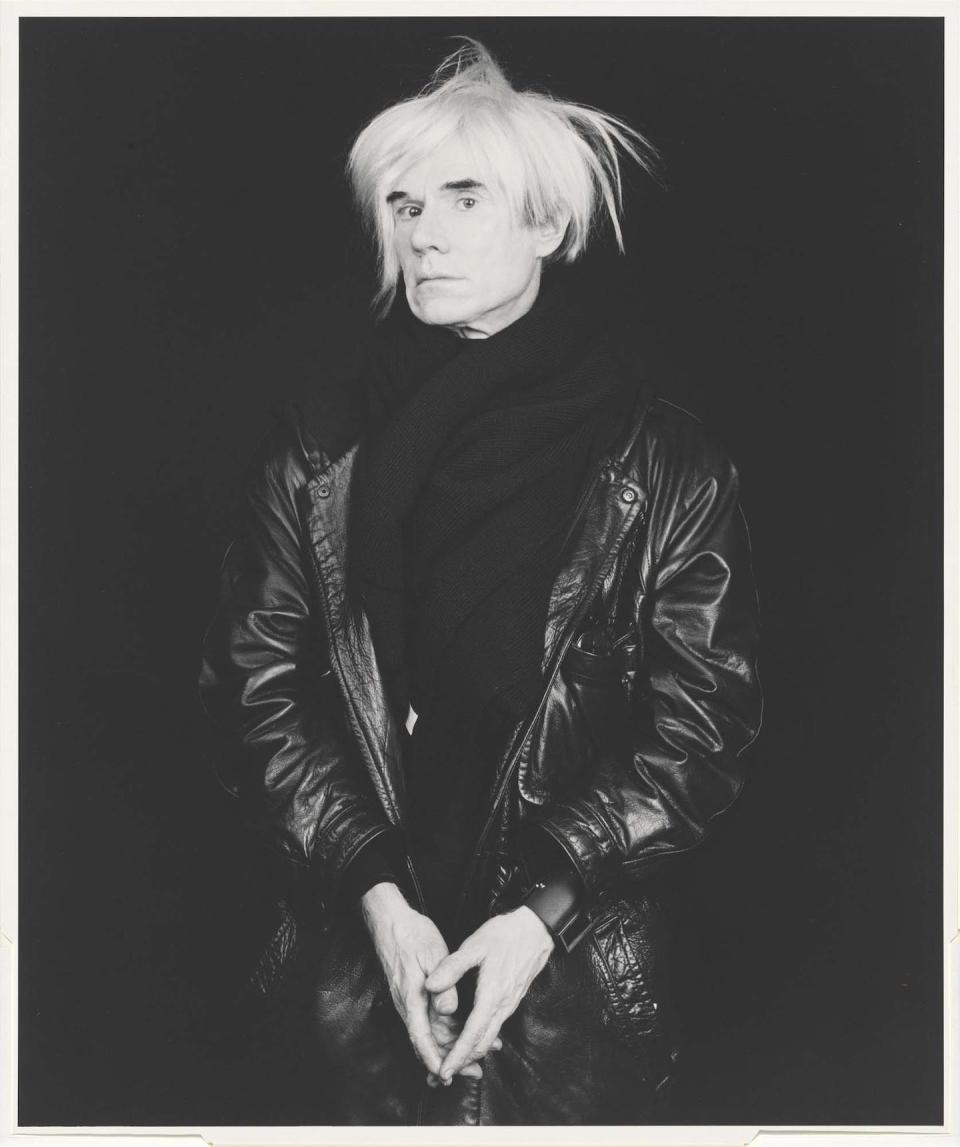

Here, Warhol emerges as a compulsive photographer whose images range from snapshot polaroids of the everyday, to portraits of the rich and famous, to Warhol himself in various self-portraits.

His camera was the iPhone of today, obsessively putting out images well before the phrases “social media” and “selfie” were invented.

Read more: Five reasons Andy Warhol is so popular right now

Warhol and the camera

Warhol began using a polaroid camera in 1957 to record himself and his friends. He was a leading magazine illustrator in New York and he moved to using the camera as a source for imagery in commissions such as a photo spread for Harper’s Bazaar in 1963, and a cover image for Time Magazine in 1965 – both on display in the exhibition.

Photography for Warhol was a key part of his working method, even though some of his images have a snapshot quality.

He famously said:

I think anybody can take a good picture. My idea of a good picture is one that’s in focus and of a famous person doing something unfamous.

By 1961 he was using his photo-based imagery for his pop art silkscreens in his Campbell’s Soup Can series. His polaroid photographs continued to be the basis for many silkscreens, such as his exuberant Mick Jagger series (1975), co-signed by each.

His Ladies and gentlemen (1975) captured Black and Latino trans and drag queens. The models were sourced from the Gilded Grape bar, a nearby haunt of Factory photographers.

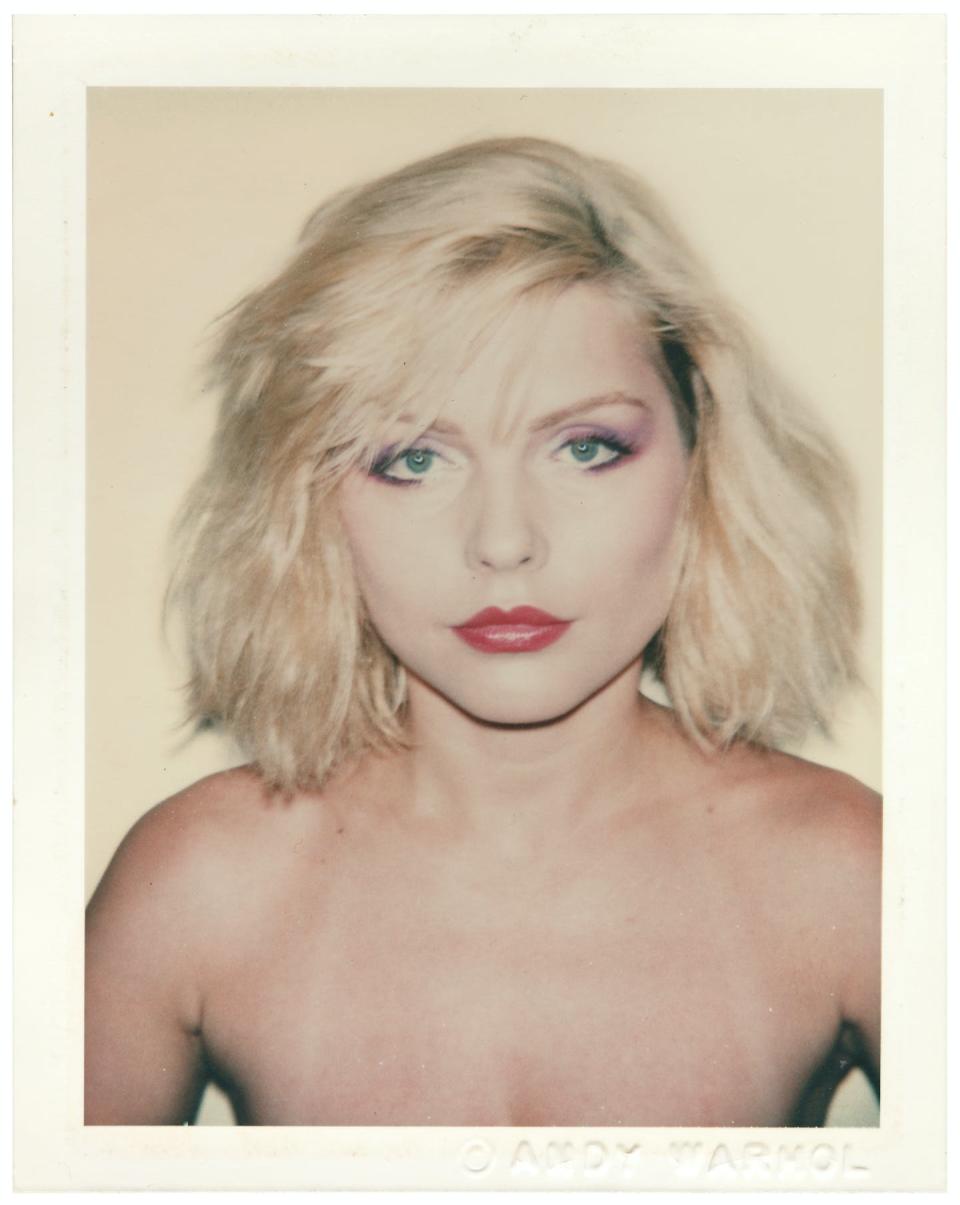

A stunning set of photographs on show come from his time in the 1970s and ‘80s producing gelatin-silver photo portraits of the celebrity figures based on initial Big Shot Polaroid images.

The dazzling array, which includes David Hockney, Henry Kissinger embracing Elizabeth Taylor, Liza Minnelli and Joseph Beuys, come from a mix of polished and in-situ photoshoots.

Late in his relatively short life, Warhol began stitching photographs together. Empire State Building (1982), showing multiples of the same image in grid formation, signals this new direction.

The Factory

This isn’t just an exhibition of Warhol, but also of his collaborators and contemporaries. The exhibition begins recreating the famous silver-lined Factory, the studio of Warhol and fellow photographers from 1964-68.

The Factory is remembered now as a site of legendary photographs and experimental films.

Warhol’s loosely scripted and silent experimental films on show from this time include the touchingly intimate Haircut (1964) and the delightfully chaotic Camp (1965). The “actors” were all, in fact, friends and acquaintances.

You sense the intensity of life there. Billy Name, the Factory’s archivist, said

it was almost as if the Factory became a big box camera - you’d walk in, expose yourself and develop yourself.

In this exhibition, Warhol’s photographs sit alongside photographs from Name, Steve Schapiro, Brigid Berlin and Robert Mapplethorpe.

Warhol himself is the subject in some photographs. Warhol would hand the camera around to other photographers like Jill Krementz who would capture him on film.

She is the photographer of Andy and Hitchcock, but the image is credited to Warhol, as often happened.

Other polaroids on show include Warhol’s homoerotic male torsos (1977), and the kissing series by Warhol’s collaborator Christopher Makos for a Valentine’s Day issue of Interview magazine, including Andy kissing John Lennon (1978).

Fleshing out the character

This is a large exhibition of 250-plus exhibits, including marked-up contact sheets, photobooth strip images, various cameras including the polaroid camera, issues of Interview magazine featuring Warhol’s photographs, and a video of his last exhibition in London in 1986 (he died unexpectedly in February 1987).

The final painting on show from that exhibition is Warhol’s camouflage-covered Self-portrait no. 9 (1986), an image that could be a composite of the many photographic portraits such as Makos’s Andy Warhol in American Flag, Madrid (1983).

The many portrayals of Warhol himself add flesh to his reputation as self-seeking, but they also penetrate the mask he so successfully cultivated. The Altered Image by Makos shows Warhol with a blond wig and wearing female make-up.

Makos recalled Warhol saying “I want to be pretty, just like everyone else”.

Read more: Andy Warhol still surprises, 30 years after his death

An astounding output

This exhibition is a wholly immersive time capsule capturing life in New York for Warhol and his circle in the 1960s, '70s and early '80s. It shows just how astounding Warhol’s output was as a photographer, and how photography underpinned his entire oeuvre.

As Makos observed at the opening, he had seen many a Warhol exhibition, but never one that captured this side of Warhol – and so perfectly too.

It is well worth a trip to Adelaide. It is not a touring exhibition and brings together key work from international and national collections.

The only inexplicable aspect is the lack of an exhibition catalogue, from a gallery with a reputation for producing prize-winning catalogues. Exhibitions are, by their nature, ephemeral events; the record lies in the catalogue.

For a groundbreaking one like this, presenting a new side to Warhol and his collaborative photographic practice, a record is needed.

Andy Warhol and Photography: A Social Media is at the Art Gallery of South Australia until May 14.

Read more: Did pop art have its heyday in the 1960s? Perhaps. But it is also utterly contemporary

This article is republished from The Conversation is the world's leading publisher of research-based news and analysis. A unique collaboration between academics and journalists. It was written by: Catherine Speck, University of Adelaide.

Read more:

Catherine Speck (with Joanna Mendelssohn, Catherine De Lorenzo and Alison Inglis) received ARC funding to research Australian exhibition history.