In pictures: A lookback at student protest movements in the US

Students have established encampments and occupied campus buildings to protest Israel’s war in Gaza, roiling college campuses across America. Many of them say they’re inspired by the long – if often turbulent – history of university activism in the United States.

As universities grapple with how to address the protests, some have called in state and local authorities to disperse participants and take down their encampments — resulting in tense confrontations with police and mass arrests.

Students, often joined by faculty, remain adamant that they will not abandon their encampments until their schools meet their demands — saying their actions in support of Palestinians follow a tradition of student-led social movements.

Civil Rights protests and sit-ins

While student protests for racial equality gained the most traction during the 1960s, some of the first demonstrations took place decades before the height of the Civil Rights Movement.

In 1943, student leaders at Howard University Law School began practicing what they called a “stool-sitting technique” where students would go to restaurants in Washington, D.C., that denied Black people service and remain seated, according to a historical account from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

One notable example was in April of that year when student activist Pauli Murray led classmates to a “Whites only” cafeteria and requested service.

“They requested service, and when they were refused, took their seats and pulled out magazines, pencils, pads and poetry books,” the SNCC article says. Managers closed the cafeteria within 45 minutes.

The following year, while protesters demonstrated outside, 55 Howard students staged a sit-in at another local restaurant. They sat and read books as employees refused to serve them. After losing 50% of its service that day, the restaurant’s headquarters in Chicago, Illinois, ordered management to serve the students, according to the SNCC.

The Howard sit-ins didn’t immediately lead to an end to racial segregation in the nation’s Capital, but they were later emulated by Black activists across during the civil rights movement.

In 1960, a group of four Black students from the university now known as North Carolina A&T, made history when they went to a Woolworth’s department store in Greensboro, North Carolina, and sat at a lunch counter that was reserved for White people, according to the North Carolina Museum of History. They became known as the “Greensboro Four.”

Sit-ins at the restaurant grew in the days to follow and six months later the Greensboro Woolworth’s began serving Black people at its lunch counter.

Segregation wasn’t the only issue that college students protested during the Civil Rights Era.

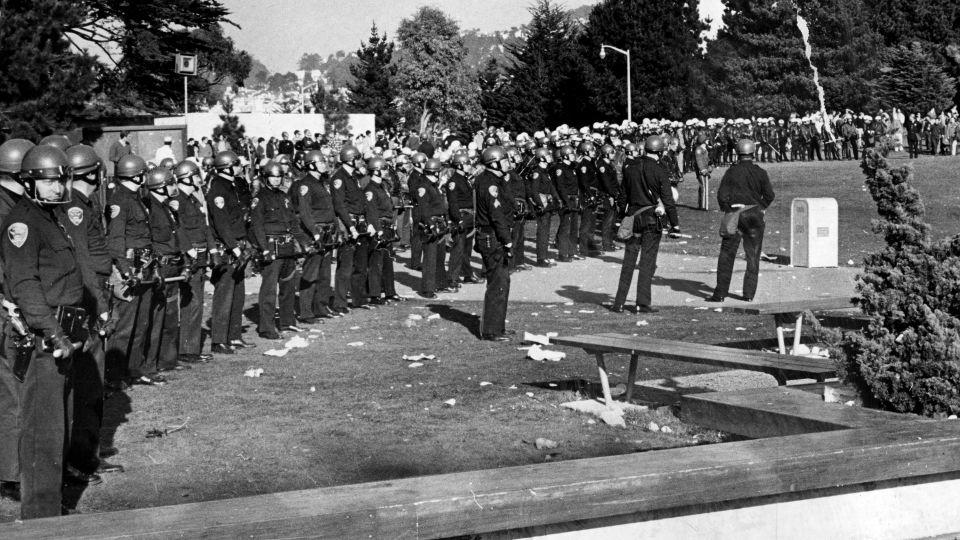

In 1968, the Black Student Union at San Francisco State University led a strike that shut down the university and forced the administration to cancel classes over three months, according to the university’s Special Collections and Archives website.

Students were demanding racial equality in admissions practices, curriculum that reflected diverse perspectives and more people of color on the faculty. They staged rallies across campus with some protests turning violent, resulting in students being arrested or beaten by police.

The university eventually agreed to meet the demands of students by establishing the nation’s first College of Ethnic Studies and Black Studies Department, increasing admissions slots for underrepresented students and committing to hiring more Black and brown faculty.

The efforts by students paved the way for other universities to create curriculum that focused on the perspectives of marginalized groups.

The Vietnam anti-war protests

The Vietnam War that began in 1955 and saw an increased presence of US troops a decade later prompted widespread protests across American college campuses by the mid-1960s.

The US intervened in an effort to halt the spread of communism in South Vietnam that had already expanded to North Vietnam and other Southeast Asian countries.

College students demanded the war’s end and spoke out against the military draft that put them at risk of being sent to fight after graduation. Thousands of students went on to protest the war in which more than 58,000 American troops were killed.

On May 2, 1964, around 400 students from Columbia University, New York University and other colleges protested US involvement during a march through New York City, calling for withdrawal of troops from South Vietnam and the end of military aid, the New York Times reported.

The University of Michigan hosted the nation’s first Vietnam War teach-in on March 24 and 25, 1965. Students, faculty members and others attended the 12-hour event, which included rallies and seminars focused on protesting the US military’s role in the war, according to the University of Michigan.

The teach-in format became popular among several other American colleges over the next several years.

Then, President Richard Nixon, who was elected in 1968 partly due to his promise to end the war, announced in the spring of 1970 that US troops had entered Cambodia. The incursion triggered large-scale protests among the anti-war movement.

unknown content item

-

On May 1, 1970, students at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, hosted an on-campus anti-war rally. Later that evening in downtown Kent, another protest that began peacefully escalated to a breakout of violence among police and demonstrators, prompting the city’s mayor to declare a state of emergency, CNN previously reported.

The mayor requested the Ohio National Guard’s presence over the next two days. Around 3,000 people gathered on Kent State’s campus on May 4, 1970, to protest the war and the National Guard’s on-campus presence.

After the crowd refused to leave, guardsmen launched tear gas at protestors and later fired shots into the crowd, killing four students and injuring nine others. The protest became known as the “Kent State Massacre.”

After Kent State, hundreds of colleges and universities shut down as a wave of student and faculty strikes and protests spread to more than 1,300 campuses. The anti-war protests ultimately led to the US withdrawing troops from Cambodia less than eight weeks after the invasion started, according to the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict.

The signing of the Paris Peace Accords in January 1973 marked the end of US involvement in the Vietnam War, and marked the end of the draft in the US, according to the Association of the US Army.

The South African apartheid divestment movement

Between the 1960s and 1980s, US student activists led a nationwide movement to pressure their universities to cut financial ties with companies that supported South Africa’s apartheid regime.

South Africa operated under a system of apartheid from 1948 until the early 1990s, during which the country’s White minority governed over the non-White majority through a series of racist and oppressive laws, including prohibitions on marriage between Black people and White people.

Laws divided the population by race, reserving the best public facilities for White people and creating a separate, and inferior, education system for Black people. Non-Whites also endured humiliating work policies, forced relocation and arbitrary treatment by authorities. One of the laws, the Group Areas Act, forced Blacks, Indians, Asians and people of mixed heritage to live in separate areas, sometimes dividing families.

The US anti-apartheid movement gained momentum through student-led protests on campuses where students demanded their universities divest from all South Africa-related investments. Students successfully pressured multiple universities nationwide, including in New York, California, and North Carolina to sever financial ties.

Among the earliest student-led protests against the South African apartheid regime came in 1966 when members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) demonstrated at the South African Consulate to the United Nations.

Students marched in solidarity with renowned anti-apartheid activist Nelson Mandela, who had been sentenced to life in prison in June 1964. Mandela would ultimately spend 27 years in prison for opposing the apartheid system in South Africa, according to the African Activist Archive.

The SNCC also cosponsored a demonstration with Students for a Democratic Society and the Congress of Racial Equality at Chase Manhattan Bank in New York, demanding that the bank stop financing apartheid by giving loans to South Africa, according to the African Activist Archive.

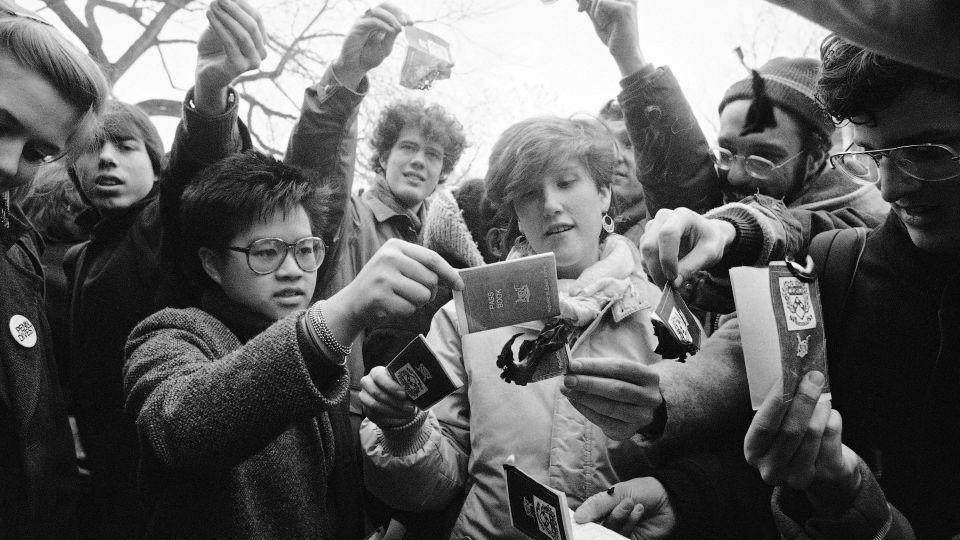

Decades later, the calls to divest from South Africa’s apartheid regime continued at Columbia University where, in 1985, students chained the doors to an administrative building shut and blocked the entrance for nearly a month.

The university threatened to expel students and sent out disciplinary notices, as community leaders such as Jesse Jackson and Desmond Tutu expressed their solidarity with the students, according to the Global Nonviolent Action Database. Immediately after the blockade ended, university trustees agreed to consider divesting the university’s $39 million portfolio of stocks in US companies doing business in South Africa.

Later that year, Columbia became the first Ivy League school to divest holdings in companies that supported South Africa.

Thousands of University of California Berkeley students also held protests in 1985, demanding the university withdraw financial holdings in companies doing business with South Africa, according to the University of California, Berkeley Library. The following year, the university divested itself of $3 billion in South Africa-related stock holdings.

Students at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill also launched an anti-apartheid movement in 1985 that ultimately influenced their administration to divest from their holdings in 1987, according to the University of North Carolina libraries.

The actions of students across the country contributed to a growing international movement to isolate South Africa’s apartheid regime and pressure it to abandon its racist policies, which it ultimately did through a series of steps – including the release of Mandela in 1990. Four years later, Mandela won the country’s first democratic election, making him South Africa’s first Black president.

Students and the Black Lives Matter movement

College students across the country have played a key role in the growth of the Black Lives Matter movement which stemmed from protests following the deaths of Trayvon Martin in 2012 and Michael Brown in 2014.

The demonstrations demanded an end to police violence against Black men and spilled over onto college campuses.

In December 2014, some 200 students at Harvard University protested Brown’s death after a grand jury decided not to indict Darren Wilson, the White police officer who killed him. Some students wore red X’s on their backs to symbolize Black people being targets. Others, staged what they called a “die-in” by lying on the ground near the feet of the campus’s John Harvard statue.

Then, in 2020, the police killing of George Floyd sparked racial unrest in Minneapolis and beyond.

Floyd’s death came during summer break for most colleges and at the height of the pandemic when many students were in lockdown at home. Many students joined the protest movement that swept the nation that summer and some universities also found ways to organize.

On June 5, 2020, more than 400 medical students, faculty and medical professionals at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine knelt for eight minutes and 46 seconds – the length of time that police held Floyd down – in a silent protest of his death. One protestor held a sign that read “Legalize being Black,” in a photo shared by the university.

But the Black Lives Matter protests were about more than just the ongoing fight against police violence in Black communities and groups that aligned with Black Lives Matter successfully rallied for more nuanced issues.

In 2015, Columbia University became the first college in the US to divest from private prison companies after student protesters demanded it. That same year, Georgetown University protests resulted in the administration agreeing to rename two buildings that were named after college presidents who sold slaves.

Notably in the fall of 2015, Black students at the University of Missouri at Columbia began protesting the racism and discrimination they were experiencing on campus.

The university’s leadership, the students said, had not done enough to address the tense racial climate of campus. Their list of demands included additional Black faculty, racially inclusive curriculum, more resources for social justice centers, and the removal of then-president Tim Wolfe.

Their demonstrations gained the support of the university’s Black football players who refused to participate in activities until Wolfe was removed. In November of 2015, Wolfe resigned.

CNN’s Clint Alwahab and Harmeet Kaur contributed to this report.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com