People are getting sick of working in the “sharing” economy

We may have already reached peak “sharing” economy.

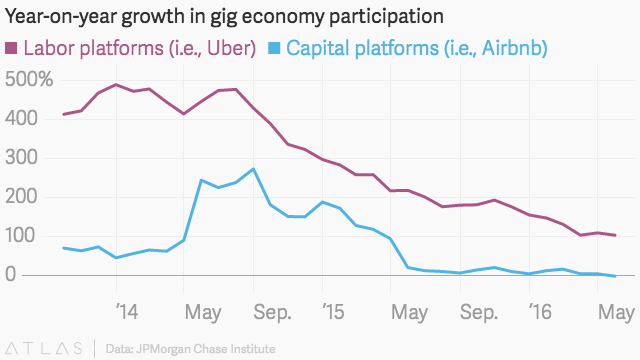

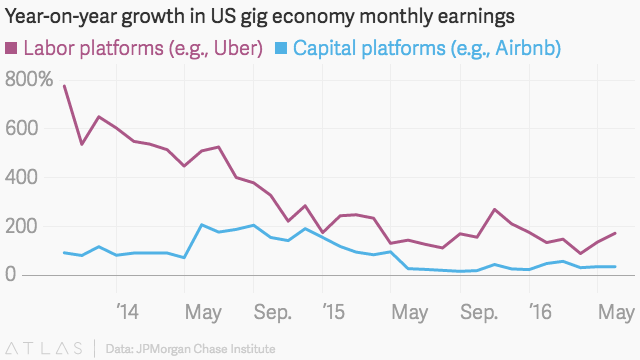

Average monthly earnings on “labor” platforms such as Uber, which use technology to match workers (like drivers) to people who need a service (like riders), peaked in June 2014, according to new data from the JPMorgan Chase Institute, the research arm of JPMorgan Chase. On “capital” platforms such as Airbnb, which help people rent out assets like a car or spare room, the share of US adults participating has declined from the previous year.

On both types of online platforms, wages are growing more slowly as is overall participation. And retention is awful: 52% of people working for labor platforms quit within a year, and 56% of those on capital platforms vacate in the first 12 months.

Participation in the “sharing” or “gig” economy was once touted as the future of work in America. But the new data from the JPMorgan Chase Institute suggests that isn’t the case. Instead, wages for workers have gotten worse as many of these companies—Uber and Lyft, to pick two examples—have cut pay rates to make prices more attractive to consumers. And the jobs themselves appear to have served as stop-gap measures for people who were unemployed or had fallen on hard times during and after the recession.

As the US economy has improved—with six years of unbroken job growth and even an uptick in wages—a greater share of those gig participants are finding better jobs. So they’ve stopped or cut down on their Uber and related gig work.

“It doesn’t look like [gig work] is becoming more lucrative for people,” says Fiona Greig, co-author on the JPMorgan Chase Institute report. “As the labor force strengthens in general, more and more people have better options.”

Jobs on these online platforms were always tenuous. “Labor” companies like Uber, Lyft, and TaskRabbit have made a practice of hiring their workers as independent contractors rather than employees. The setup means workers get more flexibility—setting your own schedule is a big talking point—but don’t get benefits such as health care, a guaranteed minimum wage, and other protections offered by full-time employment in America.

Previous work from the JPMorgan Chase Institute found that the people working for companies such as Uber were typically doing so to offset shortfalls in their monthly earnings. The poorer those workers were, the more they also depended on their gig income.

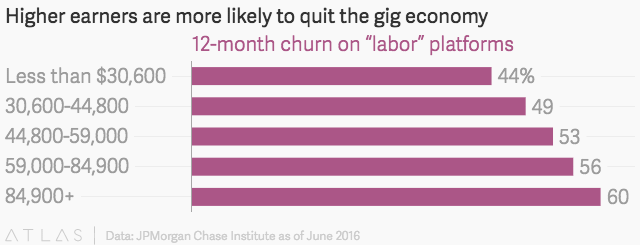

People in more stable financial situations, however, are more likely to quit gig work altogether. According to the JPMorgan Chase Institute, 56% of people employed somewhere other than an online labor platform drop out within 12 months. For those whose only work is on online labor platforms, that figure falls to 37%. Similarly, people with higher incomes are more likely to cease working for companies like Uber.

None of this is great news for investors or managers of sharing economy startups. The retention figures should alarm startups that spent heavily to build up legions of independent contractors, then struggled to keep those people sticking around. In early 2015, a paper from influential labor economist Alan Krueger found that only about 55% of Uber drivers remained active one year after starting. That metric appears to be getting worse, not better.

Sign up for the Quartz Daily Brief, our free daily newsletter with the world’s most important and interesting news.

More stories from Quartz: