Opinion: We Germans are making Trump ‘thunderstorm’ plans

Editor’s Note: Anna Sauerbrey is the foreign editor at German newspaper Die Zeit. The views expressed in this commentary are her own.

It’s 9.00 a.m. on a Sunday morning in early Spring, and we are waiting for the kids to come out onto the soccer field. Some of us are holding coffee cups. We have all gotten up early to take our fourth and fifth graders to this south-eastern district of Berlin, where they will be playing the Köpenicker FC in just a bit.

The conversation revolves around school and recent vacations, as I ask my fellow soccer moms and dads about the US election, explaining that I am working on a piece for CNN opinion. Do they follow US politics? And what do they think about it?

“I’m very worried,” says Jörg, who has been with our club forever and whose 18-year-old son Miguel is our kid’s coach. Jörg works service shifts for a local train company and whenever his hours allow, he tells me, he watches the late-night political talk shows which frequently discuss the possibility of a second Donald Trump presidency.

“To me,” he goes on, “Trump seems like the leader of a sect. His supporters would follow him whatever he does. That’s scary.” If Trump is elected, Jörg is convinced, he would withdraw American troops from Europe and stop aid to Ukraine.

“I’m scared, too,” says Eda, who teaches politics at a Berlin middle school, and Piero agrees. Piero is an urban researcher and lecturer from Italy and has been living in Berlin for many years now. Both Piero and Eda follow US news closely, like Jörg.

Piero says many things about this election remain incomprehensible to him. He is startled by the Biden-Trump rematch. “The Democrats have failed to build a successor when there was still time,” he says. “That I just don’t understand.”

Six months ahead of the vote, this soccer field conversation reflects the German view of the US elections quite well. Conversations do not necessarily circle around it naturally outside the Berlin politics bubble. After all, there are enough things to worry about: the war in Gaza, the war in Ukraine, finding a plumber in an economy increasingly marked by labor shortage and making ends meet after a period of high inflation.

But when I ask about it, I often find that American politics is there at the back of people’s minds. The election is like a thunderstorm in the distance that might or might not come down on us, and many people monitor its path.

The war on Europe’s doorstep

US elections have always been intensely reported on in Germany, but this time, there’s an added sense of tension. Since Russia began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Germany and Europe’s long-time security dependence on the United States is at the heart of the political debate.

European countries have started to step up. Germany has increased its defense spending, is building its defense industry and has spent billions on military and financial aid to Ukraine.

Still, without US support, Ukraine’s situation – and therefore, Europe’s – would be dire. The US is both our lifeline and a vulnerability. And people sense it.

At a campaign rally earlier this year, Donald Trump recalled how he once told a European leader he would “encourage” Russia “to do whatever the hell they want” to any NATO member country that didn’t pay their “bills” - meaning, if they didn’t live up to their NATO spending pledges.

Despite the obvious, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has recently taken to publicly playing down the importance of the US elections to Germany and Europe. Asked about the future of NATO if Trump wins, at a press conference in late April, he said he was “fairly confident” that NATO would remain stable “in the next decades.”

“There will be new presidents all the time,” Scholz said casually, referring to the United States.

It was a rather obvious attempt to soothe the worries of German citizens such as my fellow soccer mums and dads, but if you ask me, it’s futile. I also find it unlikely that the Chancellor’s exaggerated composure reflects his true thinking.

When I speak to officials within the German administration, I pick up a rather different mood. Many are busy bracing for the known – and unknown.

Bracing for the Trump thunderstorm

It’s a Monday night, in an office somewhere in a vast labyrinth of uniform corridors in a large government building in Berlin. A somewhat tired looking senior government official sits down in an armchair to discuss how Germany is preparing for the outcome of the US elections, for both possible outcomes, as he stresses several times. He asks not to be named, to discuss sensitive matters.

First, he says, there are efforts to try to get to know and build relations with people close to Trump, Republican senators, representatives and governors. In September last year, Germany’s foreign minister Annalena Baerbock herself went on a long tour, touching down, amongst other places, in Texas, where she met with Governor Greg Abbott. Many other German diplomats and officials are touring the US, too, particularly the south and center, to connect.

Second, he says, the administration is trying to build awareness in Germany’s business world that things might get rough, especially in case Trump wins. German US-watchers and diplomats widely expect Trump would slap new tariffs on European goods imported to the US and think he might try to force European companies to cooperate more closely with the US on containing China. But even during a second Biden administration, things might get tougher, the official says. He also expects Congress to stay volatile even if Biden wins.

Third, Germany is raising the question of what happens if Trump is elected, in meetings with its close European allies, such as Poland and France, the official says. “If Donald Trump is reelected, we have to try to stick together in the European Union, and Poland, France and Germany would have to lead the way,” he says. If Europe manages to “stick together,” its chances to extract concessions from Trump might be better than many doomsday analysts currently think, he adds. After all, the US depends on the European market, too.

It’s an optimistic view, based on the assumption that Trump will act rationally, as a deal-maker, if elected. But what if this assumption is wrong? What if Trump tries to take America out of NATO or creates a “dormant NATO,” a NATO existent only in name?

Even if Biden is re-elected, or Trump proves to be more rational than feared, America’s democratic backsliding in the past decade has already deeply impacted how German society views America - and will likely continue to do so, no matter what the outcome of the elections is.

The American dream no more

Back on the soccer field, my conversation with Eda turns to sports. Eda is wearing a Dallas Mavericks shirt. Later that day, the Mavericks will play the LA Clippers, and Eda is a huge NBA fan. She has never been to the US but says she has vowed to go if the Mavericks ever get to the finals, no matter how expensive the tickets.

Like many in our generation – on the cusp of Generation X and Millennial - Eda and I are very much into American culture. Through all the ups and downs in US-German political relations, we agree, America has stayed a big dream.

We were politically socialized during George H. Bush’s presidency, in fact the first time I ever went to a demonstration as a girl was to protest the first Gulf war.

But we also remember the euphoria when America elected Barack Obama to be its first Black president. Obama was venerated like a star in Germany, and many of the other parents on the soccer field remember vividly when he came to Berlin in 2008, how traffic came to a standstill because 200,000 flocked to the Siegessäule, the Victory Column, to see him.

US-German relations have never been just about trade, military cooperation, or the nuclear umbrella. It is also America’s soft power, its cultural-political allure, that has brought generations of Germans to view it as natural partner.

Europe’s hard right is watching America closely

In the past decade, however, that sentiment has shifted. For many younger generation Germans, America has become something of a dark force that fuels anti-democratic movements, rather than the light that emanates from the beacon of freedom.

On a Friday afternoon, Schahina Gambir gives me a call. She is a representative for the Green party at the Bundestag. Gambir was born in Kabul in 1991 and has grown up in a rural area in northern Germany. She is a member of the committee for foreign affairs but also works on human rights issues.

The US elections, she says, will of course have an impact on Europe’s security. But they will also be felt in German society. “Debates in the US resonate here and could shift Europe further to the right,” she says. “Right-wing networks in Europe have connections to right-wing networks in the US. US conspiracy theories spread here and have fueled, for example, the anti-vaxxer-scene here in Germany.”

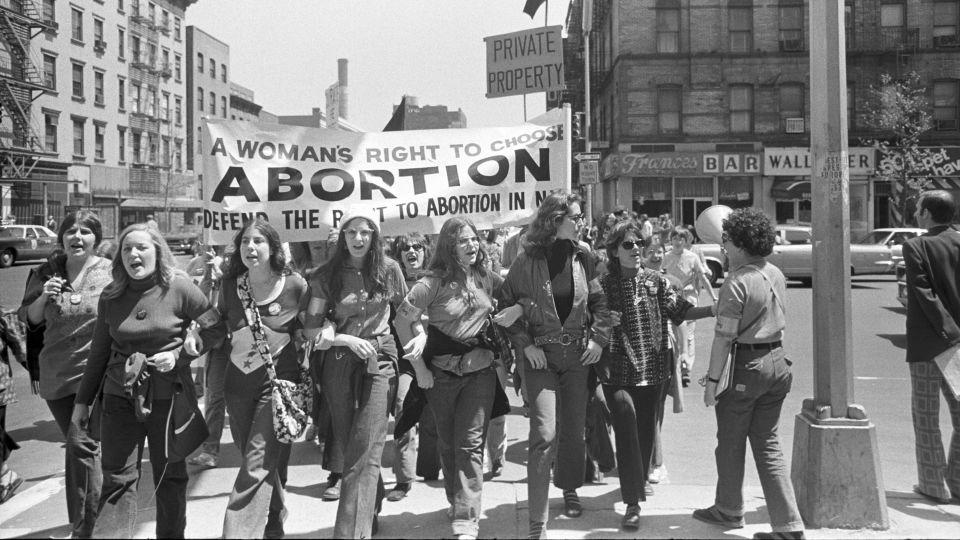

As a young woman, she says, she is also worried the US debate on abortion rights could influence Europe. “The United States were one of the first countries to legalize abortion in 1973, they were a model for others. Now, they are moving backwards,” she says of the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade.

“I am worried that the rights we have thought of as established, as a given, might be questioned, here, too, like they are in the United States,” says Gambir. Not just abortion rights, she adds, but also the rights of queer communities and people of color.

As a 32-year-old, Gambir does remember the Obama years. She has travelled to the US, her sister lives in New York and loves it. Many of today’s German teenagers and college students, however, only know the US as Trump country, a once great democracy on a slippery slope. Another Trump presidency would not only put Germany’s security at risk, but also manifest this view of the US for another four years.

On the soccer field that day, our kids easily win their game. Eda and her son leave rather content. Later, she sends me a message: The Dallas Mavericks have lost. She adds a crying emoji.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com