Opinion: California law requires police to fix these bad policies. So why haven't they?

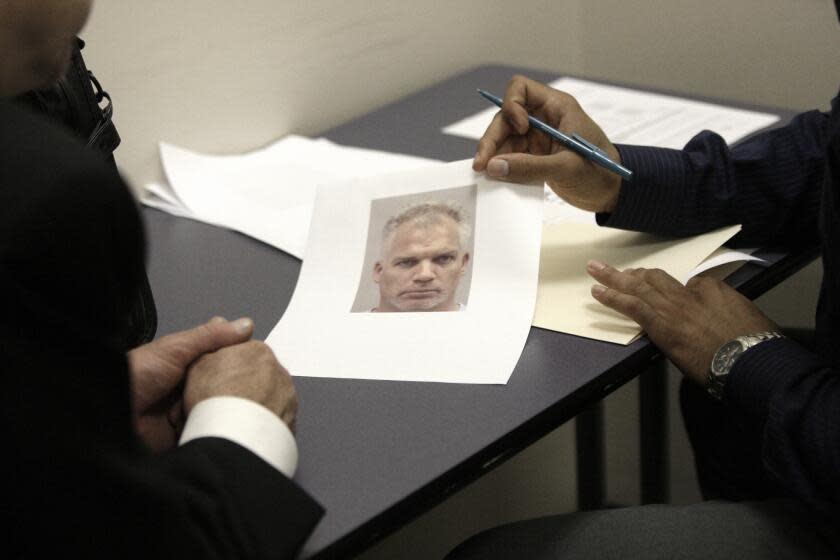

Dozens of people across California have been wrongly convicted of crimes largely because of law enforcement officers’ flawed handling of eyewitness evidence. Courts have found instances of eyewitnesses feeling pressured to make an identification from a lineup even when the true culprit wasn’t present; making shaky identifications that were ultimately presented at trial as smoking-gun evidence; and choosing from lineups of photos in which some bore no resemblance to their description of the suspect, making the police’s preferred choice more obvious.

That’s why my colleagues at the Northern California Innocence Project and I rejoiced six years ago when the state Legislature passed eyewitness identification reforms that we helped craft. The law now requires police to use evidence-based practices in handling eyewitnesses. It’s based on decades of scientific research into the causes of inaccurate and unreliable eyewitness testimony — the kind that has put innocent people in prison for decades and even for life.

Read more: Opinion: 'Know why I pulled you over?' Fortunately, California police can't ask you that anymore

As of 2020, the law requires California police agencies to conduct “blind” lineups in which the administrator doesn’t know the suspect's identity; admonish eyewitnesses that the perpetrator may not be in the lineup, that they don't have to make an identification and that the investigation will continue even if they don’t; ascertain and document an eyewitness’ confidence in any identification; use photos that generally fit the eyewitness’ description; and record the entire identification procedure.

Unfortunately, our rejoicing over these reforms has faded considerably since they were put in place. While the state’s police departments have generally acknowledged their obligations under the new law, many are failing to comply with it.

Read more: Editorial: L.A. is now paying the price for the tough-on-crime era

A new study led by the Northern California Innocence Project found that only 49% of the agencies examined were using admonishment forms that contained all of the legally required lineup instructions. Most of the remaining agencies were using the same forms they had used since at least 2010, with no changes to reflect the 2018 law.

Compounding the problem is Lexipol, a for-profit company that produces most California police departments’ policy manuals. The company created an eyewitness identification policy that wrongly downplays or misrepresents law enforcement’s obligations.

For instance, throughout Lexipol’s eyewitness identification policy, the law’s uses of the word “shall” are replaced with “should,” suggesting the required practices are discretionary rather than mandatory. Lexipol’s policy also wrongly implies that witness' identifications don’t always have to be recorded.

It’s true that police departments bear the ultimate responsibility for ensuring that their policies and practices comply with the law, and Lexipol notes that contracting agencies are free to review and modify their master manuals. But our research found that the overwhelming majority of law enforcement agencies using a Lexipol manual — 90% — largely adopted the company’s eyewitness identification policy as written.

Lexipol should change the flawed language in its policy to make it clear that these practices are mandatory. Moreover, defense attorneys should challenge and courts should suppress identification evidence from police departments that fail to follow the law.

Preventing tragic eyewitness mistakes and wrongful convictions depends on police following this law.

Consider Northern California Innocence Project clients such as Franky Carrillo Jr., Miguel Solorio and Joaquin Ciria, who were wrongfully incarcerated for 20, 25 and 32 years, respectively. All three are men of color who couldn’t overcome wrongly obtained, false eyewitness identifications at trial. In each case, juries took these tainted identifications as convincing evidence of guilt.

The days of such blind acceptance must end. Nothing less than full compliance with the law will protect the next innocent person from going to prison.

Todd Fries is an attorney and the executive director of the Northern California Innocence Project at Santa Clara University School of Law.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.