Opinion: A big problem with how we talk about race today

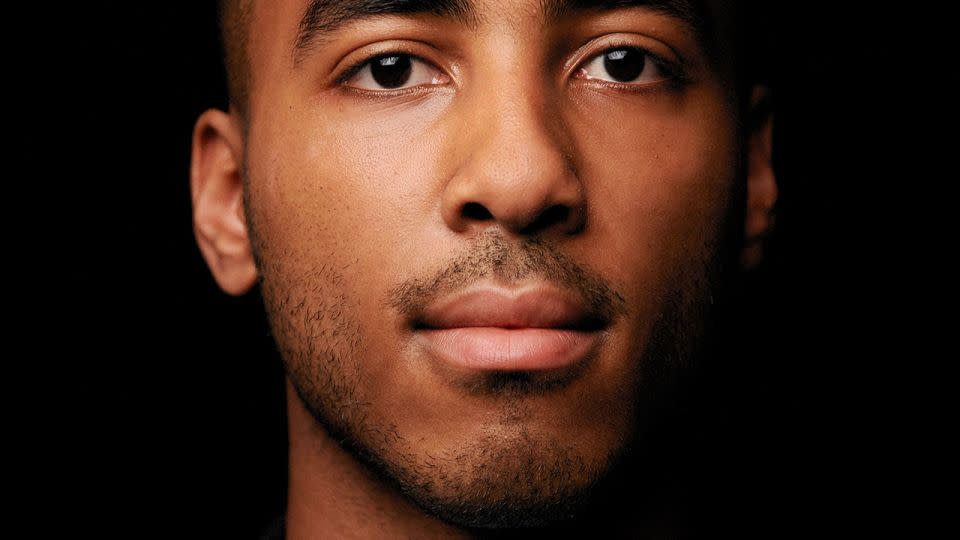

Editor’s Note: Coleman Hughes is a writer, podcaster and opinion columnist who specializes in issues related to race, public policy and applied ethics. His writing has been featured in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, National Review, Quillette, The City Journal and The Spectator. He is a contributor at CNN and the Free Press, and he appeared on Forbes’ 30 Under 30 list in 2021. This piece has been adapted from “THE END OF RACE POLITICS: Arguments for a Colorblind America” by Coleman Hughes (published by Thesis, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group). The views expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

I’ve always found race to be boring. Sure, it can be good source material for jokes at a comedy club. But in most real-life situations, a person’s race tells you next to nothing about them. Of all the qualities you could list about somebody — their personality, beliefs, sense of humor and so forth — their race is just about the least interesting characteristic you could name.

So if I find race to be a meaningless trait, why write a whole book about it? The answer is simple: I didn’t choose the topic of race; it chose me.

I am what you would call “half-Black, half-Hispanic” or, simply, “Black.” For most of my young life, I rarely thought about my racial identity. I had Black friends, White friends, Asian friends, Hispanic friends and mixed-race friends. But I didn’t think of them as “Black,” “White,” “Hispanic” and “mixed race.” I thought of them as Rodney, Stephen, Javier and Jordan.

For the most part, the people I grew up around seemed to share my lack of interest in race. They agreed with Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous dictum about the content of one’s character trumping the color of one’s skin — even if collective overuse had already made it a cliché. On the rare occasion that some petty person did try to use race as a weapon — to bully someone, for instance — the dominant value system would come down on them like a tornado. They would be ostracized and punished. Where I grew up in Montclair, New Jersey, racists existed, but they were the exceedingly rare exceptions that proved the overwhelming rule.

Montclair’s well-loved public schools were my home until the sixth grade, when I enrolled at a fancy private school several towns away. Though the education I received at this new school was undoubtedly better, the social transition was awkward. The main locus of this awkwardness was my large, voluminous afro.

As I write in my book, “The End of Race Politics,” in my hometown public school, where around 1 in 3 students was Black, afros were commonplace. Kids of every race were used to seeing them. But at Newark Academy, I was a novelty. There were only four Black students in an entering class of over 60 kids, and most of the non-Black students did not come from racially diverse towns like Montclair. Many of them had never known somebody with an afro. What began as an understandable curiosity about my hairstyle grew into a ubiquitous and apparently irresistible urge to touch it — usually ruining whatever preparation I had done that morning to get it looking just right.

I hoped this was just passing curiosity. But as the weeks turned into months, it became clear that the urge to touch my hair was insatiable.

Eventually I broke down. Thoroughly frustrated with my peers, I cried hot tears to my parents. I was tired of having my hair ruined by my classmates’ curiosity, tired of being treated like a novelty act. I don’t remember whether the problem stopped after my parents talked to the school principal. But what I do remember is that by seventh grade the afro was gone, replaced by an unassuming fade (in retrospect, a way better choice anyway).

Four years later, when I was 16, the higher-ups at Newark Academy offered me the chance to attend a three-day event in Houston called the People of Color Conference. I said yes, jumping at the opportunity to miss three days of class. Misleadingly, the conference was not just for people of color but for private school students of all races — hundreds of us from around the nation.

Though I wouldn’t have known to call it this at the time, the conference was essentially a three-day critical race theory and intersectionality workshop. It was there that I first heard terms like systemic racism, safe space, White privilege and internalized oppression — ideas that were fringe in 2012 but would sweep through elite universities just a few years later. Up until 2012, I had never been immersed in a subculture where my race was considered to be important. The People of Color Conference changed that. At the conference, my Blackness was not considered a neutral fact — irrelevant to my deeper qualities as a human being. My Blackness was instead considered a kind of magic. My skin color was discussed as if it were a beautiful enigma at the core of my identity, a slice of God inside my soul.

The conference leaders taught us one idea that pertained directly to my unfortunate afro experience from middle school: a microaggression. A microaggression, I learned, was a statement or action that conveys subtle, unintentional discrimination against members of a marginalized group. Before learning this term, I had filed the afro fiasco under the heading of “difficult experiences that many kids face in middle school.” In fact, I recall thinking that it was not nearly as bad as the verbal abuse experienced by my White friend for being an unlucky mix of pale, skinny, nerdy and awkward — bullying that eventually prompted him to leave the school. Nor was it anywhere close to the mocking endured by the overweight, pimply White kid whose manner of speech seemed to be permanently slurred. In truth, it wasn’t even bullying. The kids touching my afro were never malicious, only curious. They never teased me or insulted me. And I easily got along with them in every other context. As annoying as their behavior was, the obvious goodwill behind their actions softened my judgment of them.

At the conference, however, I was taught to frame my experience differently. It was a microaggression. Whereas bullying can be experienced by anyone, only members of marginalized groups can experience microaggressions. My afro experience was placed on the same continuum as the violent racism I had learned about in history class. At one end of that continuum was Emmett Till and the brave civil rights protesters beaten at Selma. And on the less severe end of that same continuum was me. I had experienced a microdose of the same poison. I was taught that my victimization was special, and that made me special. Where my White friends had the wind of White supremacy at their backs, I faced a headwind. And everything I had accomplished in spite of it was that much more impressive as a result.

That was the ideology that I, along with hundreds of other students, absorbed at this three-day conference. The atmosphere, however, was less scholarly than it was spiritual. For instance, many of the students at the conference were gay and came from households that were socially conservative. For some, the conference was the first time in their entire lives that they could voice their sexuality out loud without fear of judgment. There was crying and hugging and warmth. In those ways, the energy in the room was uplifting.

But in other ways, it was suffocating. The teachers enforced a strict orthodoxy; dissent was never welcomed and was therefore rarely even attempted. As a kid who enjoyed debating with professors, I couldn’t help but notice, and lament, the stifling conformism.

After my brief foray into the strange, race-obsessed world of the People of Color Conference, I returned to my life as a high school student who cared about music and philosophy, and who connected with others on the basis of shared interests rather than race. I never imagined that I’d encounter this subculture again.

Then I enrolled at Columbia University.

In the three years since I’d attended the conference, the ideas I encountered there had spread to elite high schools and universities throughout the nation. During orientation week at Columbia, we were asked to divide ourselves up by race and discuss how we either participated in, or suffered from, systemic oppression. I huddled with the Black kids in one corner of the room, and watched as the White kids, Hispanic kids and Asian kids awkwardly shuffled to their respective corners.

Whatever the intent of this ice-breaking exercise, the effect was that I felt acutely aware of my Blackness. And that awareness ironically made me feel less connected to the people around me, not more. I worried that rather than approach me as a blank slate, these students would approach me as a Black man, and, by implication, a victim.

In my four years at Columbia, hardly a week passed without a race-themed controversy. In the school newspaper, students would say they experienced White supremacy routinely on campus. A professor of mine once told our class that “all people of color were by definition victims of oppression,” even as my daily experience as a Black person directly contradicted that claim. It felt as if I was dropped into a simulation where the Real Racism dial was set close to zero, but the Concern About Racism dial was set to 10. Though I found the topic of race to be boring in and of itself, the surrounding culture was obsessed with it — and was hell-bent on dragging me in.

Eventually, I became curious. Why were White students and professors confessing their inner racism unprompted? Why were Black students in one of the most progressive, non-racist environments on Earth claiming to experience racism all the time? And why were so many otherwise reasonable people pretending to believe them? Why did these kids sound more pessimistic about the state of American race relations than my grandparents (who lived through segregation) do?

The more I asked these questions, the more I became convinced that the new race obsession that brands itself “anti-racist” is in fact the opposite. It is racist, destructive and contrary to the spirit of the civil rights movement. Taken to their logical end points, the ideas I encountered first at the People of Color Conference and then at Columbia paved the way toward a social and political hell-scape where skin color — a meaningless trait — is given supreme importance.

If these ideas were confined to high school conferences and Ivy League universities, one could make the case that they are not worth worrying about. But they have infected all of our key institutions: government, education and media. Some of our most celebrated and sought-after public intellectuals routinely espouse ideas so extreme that the public has been desensitized to them.

All of this is why in my book, I argue that colorblindness is the wisest principle by which to govern our fragile experiment in multi-ethnic democracy. My hope is that this book will help people think more clearly about the long-run consequences of race thinking and race-based policy, restore our faith in the guiding principle of colorblindness and pave a constructive path forward in our national conversation on race.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com