‘Our obsession with true crime isn’t just rubbernecking — it can give us the agency we don’t have in real life’

Did you watch Take Care of Maya? Or perhaps binge Serial, following the case of Adnan Syed more closely than you monitor your own inbox? Surely you watched Making a Murderer back in the day? Chances are, you have at least heard of all of these.

Call it educational, a genuine desire to overturn miscarriages of justice, or just morbid fascination, but our appetite for true crime stories has become increasingly reflected in streaming platforms and podcast charts. I’m an avid consumer of true crime myself.

My favourite books have always been thrillers, and I’ve been known to become deeply immersed while reading about historical murders. It might sound like rubbernecking, treating real crimes as entertainment fodder, but it’s not so simple. I—and others—seek a certain amount of validation in these stories.

The statistics about male violence, femicide, and our ongoing and often unaddressed lack of safety are grim. The World Health Organization estimates that around one in three women around the world have experienced physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence, or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime. And while women are often the victims in true crime stories, they are also the largest audience for their retelling. In fact, women overwhelmingly make up the majority of true crime audiences and are twice as likely as men to regularly listen to true crime podcasts.

Charlie Webster, host of the chart-topping true crime podcast Scamanda, first approached the genre as a consumer. “True crime has been the content I've always consumed, even from a young age,” she tells me. “For me, it was definitely escapism. It absorbed my brain, because it took me away from normality.” Webster believes women in particular are drawn to true crime “because quite often, we see ourselves in stories.” “People can see their own pain in some of the storytelling,” she says. “I think that's why women love it so much, because it's a way to play out your vulnerability and your own pain.”

The idea of finding escapism in painful stories might seem off, but there’s a psychological logic behind it. According to psychiatrist Dr. Jean Kim, who has written about the intersection between mental health and pop culture, there may be a sort of self-preservation at play. Women might see watching true crime as a way to face our biggest fears, she explains. “Maybe there's something about trying to see what's going on and prevent it from happening to us,” she says. “There’s this kind of vicarious participation too, in something that's kind of horrifying and forbidden, and maybe for some reason—I'm not sure why—we're drawn to watching and participating in that, for better or worse.”

Another way of looking at it, Dr Kim offered in a blog post earlier this year, is through the lens of morality. “These stories can provide a sense of moral clarity” by offering “a moral structure to the viewer that can be appealingly straightforward and remind us of our own humanity.”

But beyond our own personal approach to watching these shows, should we pause before pressing play on the latest true crime documentary for other reasons? According to Ruth Davison, the CEO of domestic abuse charity Refuge, watching such shows could be doing more harm than their intended good of exposing the truth. “On average, two women a week are killed by their current or former partner in England and Wales. Sadly, many of these women will become the content of the increasingly popular true crime genre,” she says. “The way that true crime is reported often dramatises these events and fictionalises the victims and can even glamourise or show sympathy towards a perpetrator.”

Moreover, as viewers of true crime, we can tend to mentally separate from the reality of the story, instead viewing it from our outsider perspective in which we might inadvertently victim-blame. “Consumers of true crime often contemplate what they would have done differently or pass judgement without knowing the full reality of the situation. We must be clear, violence against women and girls is a crime, it is not something to be consumed by ‘armchair detectives’ and there is never an excuse for domestic abuse—it is an active decision a perpetrator makes,” Davison says.

And with domestic abuse in particular being such a misunderstood social issue, this can risk further impeding our wider approach to understanding, emphasising, and overcoming such crimes, she explains.

The charity Solace Women’s Aid created the Solace Test to help creators depict violence against women and girls responsibly. It involves three checks for anyone working around that topic: Is it needed, ie, does it drive the story? Is it truthful, or on the contrary, does it add to a cultural lie about violence against women and girls? And finally, is it victim-blaming?

For female viewers, when those parameters are observed, the consumption of true crime can be, in some ways, cathartic. In her book Savage Appetites, the journalist Rachel Monroe questions and analyses our collective attraction to true crime as a genre. She notes that female forensics students who were asked by researchers at West Virginia University what had driven them to their field of study cited, among other factors, “a past experience of trauma.” That trauma, Monroe notes, can be individual or societal. “Pain doesn’t have to be motivational to be a motivating force,” she writes. “Something has happened to all of us.”

We can't always get people to acknowledge our own pain. When exposed to someone's cruel behaviour, we don't always get the resolution we want. Watching true crime can offer us somewhere to turn to see those behaviours acknowledged and, sometimes, punished.

Dr. Kim compares this way of thinking with the MeToo movement. “For decades, we put up with all these things that people realised were actually a big deal. But it all got gaslighted away and minimised. So, do these shows kind of say, ‘Look, this is what really happens, this is the worst case scenario, and these are real things that happen to women and victims’? And is it a form of validation in that regard? Maybe.”

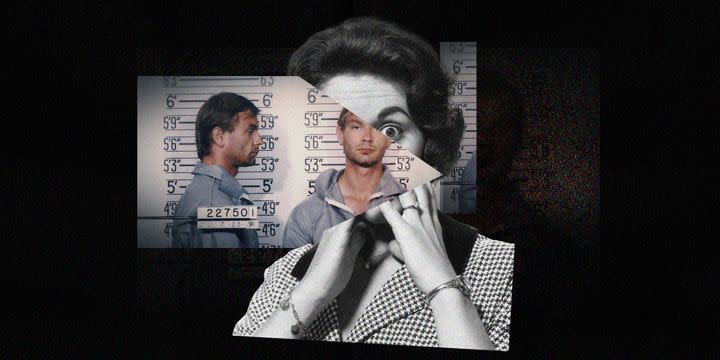

Over the past few years, we’ve seen a gradual acknowledgement of these concerns and a resultant shift in true crime programmes, wherein our attention has been directed away from perpetrators and refocused on their victims and their families. Seeking to counteract the decades of narratives that placed serial killer Ted Bundy at the centre of the story of his crimes, the 2020 documentary Ted Bundy: Falling For a Killer instead paid particular attention to Bundy’s victims, including survivor Karen Sparks Epley. The documentary was based on a 1981 memoir by Bundy’s former partner, Elizabeth Kendall and included interviews with Kendall herself as well as her daughter Molly.

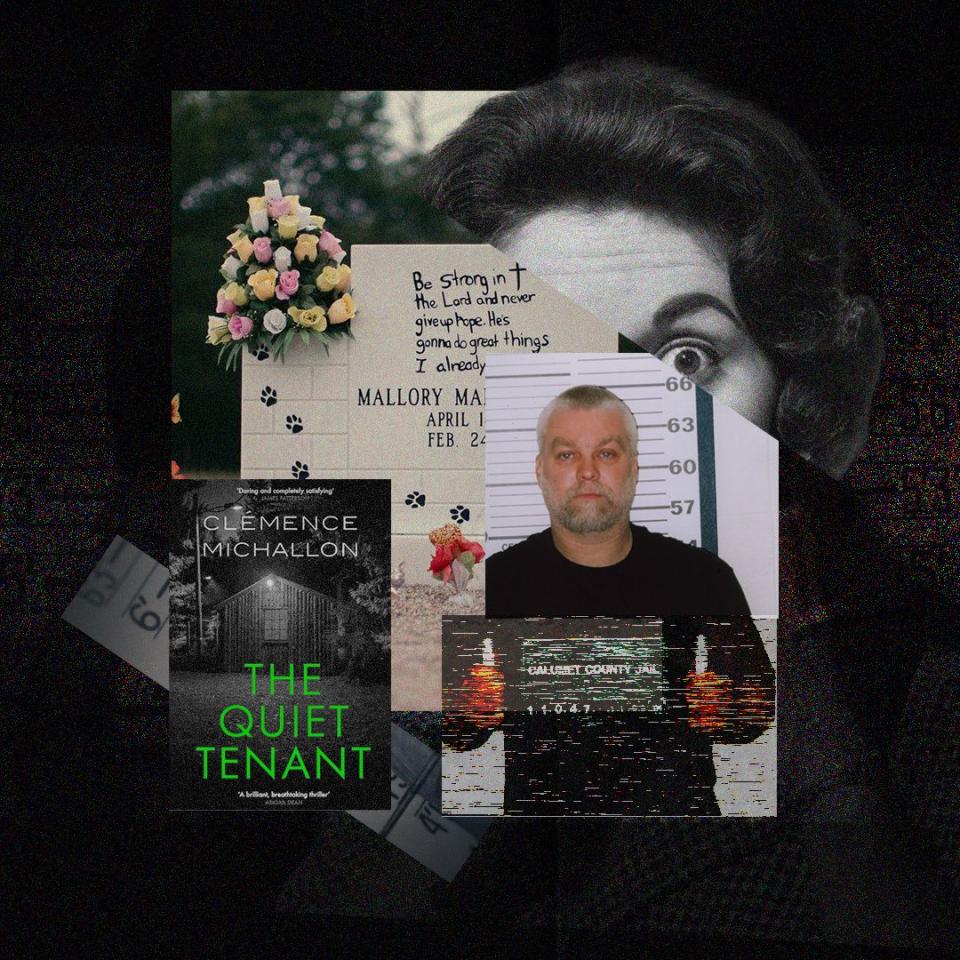

When I started working on my own psychological thriller The Quiet Tenant, which features a male serial killer, I felt a strong responsibility to focus on the female characters at the heart of the story. I knew from the onset that my serial killer character wouldn’t get to speak. It seemed more meaningful to tell the story of a man like him—a killer who has murdered eight women and is holding another one captive but is known in his local community as a kind neighbour—through the perspectives of the people most affected by his crimes. I was inspired by the changes I had noticed in my own true crime consumption.

Re-focusing the true crime angles and being selective with the stories we choose to consume can go a long way. As Dr Kim puts it: “I think it's good when they centre the victim in the story, and make sure to talk about them as a human being with a life, not just as a body or a person that died. And also talk with their families and try to show how much they went through.”

In this way, true crime can become a place of support. This is something Webster has also found through her own work. Webster has spoken publicly about surviving domestic abuse inside and outside of her household. Her 2021 documentary Nowhere to Run details the abuse she suffered at the hands of her running coach after joining a club in Sheffield. As a journalist and survivor, she has felt a deep responsibility when telling stories of crime. “I look at some of the stories I've told that have talked about my own experience, seeing and reading people's comments who reach out as, ‘I understand’ or ‘This happened to me,’ that is responsible consumption, because that can really mean so much,” she says. “People might not realise how much it means, but it means so much when you tell your story to have people just say, ‘I am with you, and I see you.’”

Refuge’s free National Domestic Abuse Helpline is available 24 hours a day 7 days a week for free, confidential specialist support, at 0808 2000 247. Or visit www.nationaldahelpline.org.uk

You Might Also Like