Mayor Bass orders police 'surge' on Metro bus and rail routes amid spike in violence

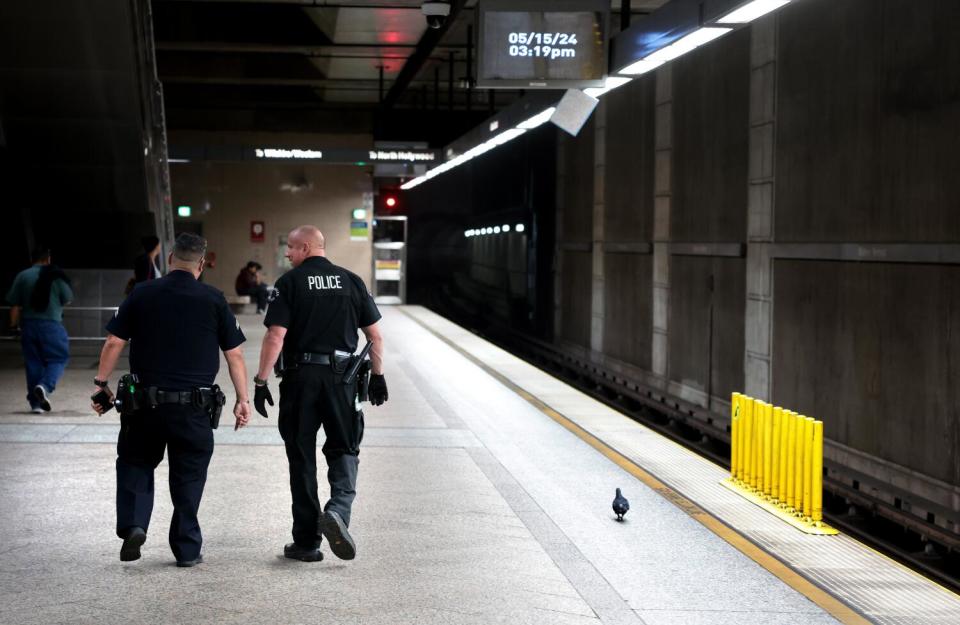

Mayor Karen Bass ordered a “surge” of law enforcement inside the region’s hundreds of buses and miles of subway system, saying Metro riders don’t feel safe after a spate of violent attacks that have roiled an agency already struggling to improve safety and increase ridership.

The move by Bass, who heads the board of the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority, marks a significant departure for the agency, which opted not to beef up law enforcement’s presence to reduce drug use, crime and disruptive behavior. Critics are coming from all sides. Some say the move is too little too late; others call the tactic doomed to fail and say it will only criminalize people who have drug addictions, serious mental illness and no housing.

“The spike in violent crime on Metro that we have recently seen against operators and riders has been absolutely unacceptable,” Bass said. “We wanted to act immediately because we understand that our No. 1 job is for Angelenos across L.A. County to feel safe.”

Pressure has been growing on Metro and Bass as they confront a near daily barrage of new attacks on passengers and drivers. Three people were stabbed in two separate incidents this week. Last month, Mirna Soza, 66, was fatally stabbed on the subway as she came home from her night shift job and a passenger captured a bus driver pleading for help after being stabbed.

“The increase in crime threatens to derail our goal of exceeding 1.2 million weekday riders, if we cannot ensure the safety of those who want and need to use the bus and rail,” Bass wrote in a motion that will be voted on next week at the Metro board meeting.

The proposal seeks to formalize increased deployment levels, although neither Metro nor the mayor’s office would say exactly how many officers that entails or for how long. It also directs law enforcement to “proactively walk through rail cars and ride buses” and ensure there are no gaps in service during shift changes. And it aims to fix all dead cellphone service spots, so that people can report crime and call for help.

Read more: Metro board ponders facial recognition, other security measures after subway killing

But critics say more police isn’t the answer. Costs are too high, eating up large portions of a proposed $9-billion budget, and so far stepped-up law enforcement hasn’t proved to reduce crime.

“In the last seven years, Metro spent over $1.1 billion on law enforcement; the budget allocations to Metro’s police contracts increase every year, and yet this has not brought us closer to an enjoyable and safe system,” said Laura Raymond, director of ACT-LA, the Alliance for Community Transit. The group represents dozens of community groups advocating for free fares, better service and other social justice issues on transit.

“Metro cannot afford to continue to waste money and time on a failing strategy.”

There are roughly 600 uniformed officers from the Los Angeles Police Department, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and the Long Beach Police Department patrolling the system, said Robert Gummer, who oversees security for Metro. There are also 200 transit security officers. It’s unclear how Metro will pay for an increase in daily deployment and whether that will mean hiring more Metro staff or contracting for more police shifts.

As it is, Metro is facing a 10% increase in cost for law enforcement in the coming budget, with no jump in deployment.

Officials have been grappling with how to make the system feel safer — even as there are ambitious plans underway for a serious expansion.

The board will soon weigh in on two light rail line extensions , the C Line farther south to Torrance and the E line eastward to Whittier.

But many of the system’s achievements get overshadowed by spates of crime.

The board’s monthly meeting last month might have otherwise been most memorable for the environmental clearances for the first segment of the Southeast Gateway Line, a 14.5-mile light rail line through the heart of the southeast county. Instead the board delved deep into how to prevent crimes on a system it is preparing to show off to the world during the 2028 Olympics. The litany of measures the board is now considering includes the feasibility of facial recognition devices and securing station gates.

The board has already sunk tens of millions of dollars into expanding its ambassador programs, design improvements and homeless outreach. In the last 10 months, it has housed 1,700 people seeking shelter on the system.

Law enforcement agencies have repeatedly defended their work, saying that many of the quality-of-life crimes that plagued the system have fallen over recent months, despite the high-profile attacks.

But within the agency, there is an uneasy relationship with the uniformed officers.

Former head of security Gina Osborn and the union representing drivers and train operators have both advocated for Metro to create its own dedicated police force. And the 13-member board — made up of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, Bass, her three appointees and regional representatives — has asked staff to investigate whether it’s feasible.

“Throwing more uniformed bodies on the platform isn’t going to increase safety on the system if the uniformed presence is not engaged,” Osborn said.

Outside law enforcement has “no ownership in the system,” she said. “Why aren’t they investing in the transit security officers who can actually establish order on the system?”

Osborn says she was fired in March after reporting to the agency’s inspector general that contracted law enforcement officers didn’t show up for work, leaving a light rail station in Santa Monica without any protection.

Adding more security may work for a month or two, she said, but after officers disappear the problem returns.

Times staff writer David Zahniser contributed to this report.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.