What L.A. renters should know now that COVID tenant protections are gone

Most renter protection programs launched during the pandemic in Los Angeles have expired, and tenants who couldn't pay rent due to economic hardships brought on by the COVID-19 outbreak must pay rent again starting Thursday.

That includes back rent owed from Oct. 1, 2021, to Jan. 31, 2023. Tenant advocates say it is preposterous to expect renters to pay the full amount from that period. The end of such renter protection programs are likely to result in many struggling renters becoming homeless or leaving the city and state altogether, said Larry Gross, executive director with the tenants advocacy group Coalition for Economic Survival.

"For those who are struggling to make ends meet, this is going to place a tremendous increased burden," Gross said. "These tenants are essentially on the track to economic catastrophe, and there's not much being done for them."

Rent increases can resume

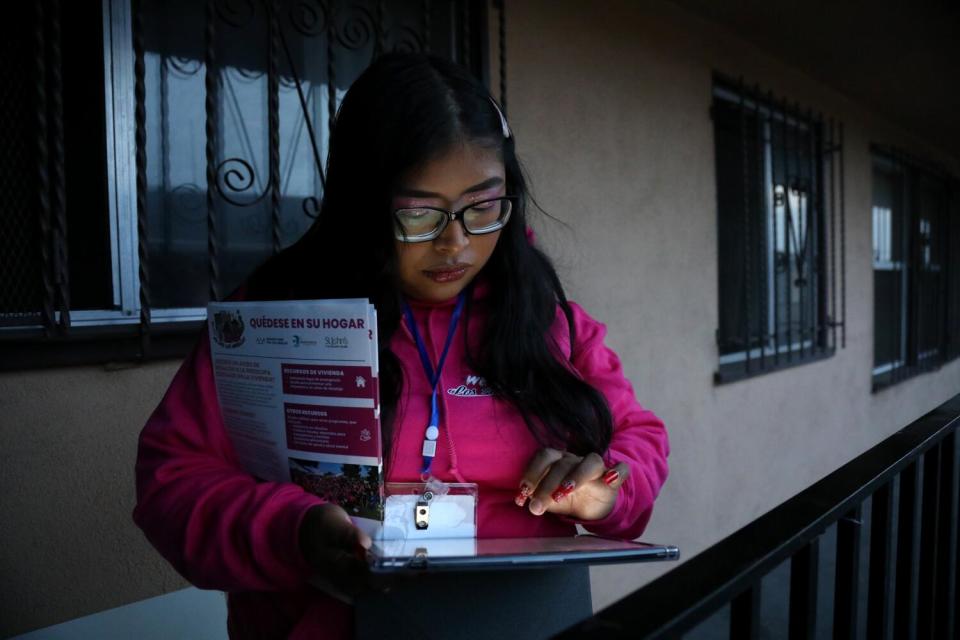

Evictions for nonpayment can resume starting Thursday, according to the Los Angeles Housing Department. Anyone who receives an eviction notice from their landlord — referred to in the courts as an unlawful detainer — should file a response to the courts within five days or risk losing their case by default. The city offers assistance for tenants facing an eviction notice at stayhousedla.org.

Landlords can also increase rent over the next four months by as much as 6% annually if they pay for gas and electric in the tenant's rental unit. This applies to rental units built before Oct. 1, 1978, and covered by the city's Rental Stabilization Ordinance. These residents cannot be evicted without just cause, but tenants in units not protected by the RSO could see higher rent increases.

"The key thing for every tenant to know is their rights, and they need to not just react to whatever notice they get for from their landlord," Gross said about rent increases and eviction notices.

Tenants should consider whether they face a legal or illegal eviction effort by their landlord. Renters can turn to legal aid clinics, such as the weekly Zoom meeting hosted by Coalition for Economic Survival, to determine what their options are and what resources they can use.

Landlords also cannot evict a tenant if they owe rent that is less than a certain threshold called the fair market rent of the unit. For example in 2024, the rent of a one-bedroom apartment is $2,006, and if a tenant owes less in rent, then they cannot be served notice, according to the city's Housing Department.

Read more: Ruben's Bakery survived pandemic and riot only to be ransacked during a street takeover

The pet stays in the picture

The city enacted a tenant law during the pandemic that would not penalize renters who took in a pet, even if the pet was not allowed under their lease agreement.

The rule remains in effect for as long as the pet is alive but does not apply to pets who moved into the rental after Jan. 31, 2023, according to the ordinance. It was meant to deter people being forced to choose between keeping their pet or keeping their housing.

Councilmember Eunisses Hernandez said the new law is designed to address the wide-ranging effects that the pandemic had on some people's lives.

"Many people lost their loved ones and were dealing with isolation from quarantine, which led many to get new additions to their families,” Hernandez said. “These pets have helped people get through difficult times, and tenants should not be evicted from their homes because of the pets.”

Rent relief from the city

Mayor Karen Bass' office encourages renters to know their rights and suggests tenants who face eviction contact the Housing Department hotline at (866) 557-7368. Tenant advocates warn renters to seek advice if they receive a notice to vacate from their landlord, rather than self-evict.

“In order to confront this crisis, we must do all that we can to prevent people from falling into homelessness in the first place,” Bass said in a statement. “Together with locked arms, we will continue our work to provide resources for the people of Los Angeles.”

The city of Los Angeles operates a rental protection program, known as United to House L.A. Emergency Renters Assistance Program, but it has had problems. The program set aside $30 million for rental relief but accepted applications only for a few weeks in September and October. So far, the program has approved about 3,200 tenants to secure rental relief of up to six months of rent, but most have yet to get their payments. About a quarter of the $30 million in funding has been dispersed, and an additional 25,000 tenants who applied for the program are still waiting for an answer.

On Jan. 26, the City Council voted to protect tenants from eviction if they were approved to receive funding through the program but have not yet received any money. That protection could extend to more renters who get approval in the meantime, which should stave off an eviction notice from their landlord.

“Tenants who have already been approved for emergency rental assistance should not be evicted while they’re waiting for their checks,” Councilman Paul Krekorian said at the council meeting. “Their landlords are going to get paid, so they shouldn’t be putting tenants out just because the city took a little longer to get them the money.”

But there is uncertainty surrounding the funding and who could qualify.

"Unfortunately, many tenants in the queue haven't been notified whether or not they're even eligible," Gross said. "So they've been holding on and waiting. Some of them waiting for letters and approval that will never come."

Read more: L.A. moves to protect renters who got a pet during the pandemic lockdown

The scope of the problem

The number of households behind on their rent in Los Angeles is between 100,000 and 150,000, according to a study conducted by the University of Pennsylvania on behalf of the city of Los Angeles. More than 10% of those surveyed last summer said they were more than a year behind.

"Households who reported being behind on rent were more likely to have children, to have a disability, to identify as Black or Latinx, and to have larger household sizes compared to other renter households," the study authors wrote.

The survey said the number of tenants behind on their rent is greater than what is projected in publicly available data from local government agencies.

According to the survey, those who are newly vulnerable to eviction in Los Angeles include about 60% — or 90,000 households — who recently fell behind on rent and could be evicted for nonpayment. The remainder fell behind on their rent payments before Oct. 1, 2021, or fell behind the last several months. The most vulnerable group in danger of eviction for nonpayment are tenants who hold graduate degrees and are less likely to be in the labor force, compared with others with outstanding debt, according to the study authors.

Among Los Angeles landlords with outstanding debt due to tenants behind on their rent, about 70% reported problems paying for repairs and maintenance and about half said they are having trouble paying property taxes and other payments. Out of the landlords surveyed, fewer than half said they would move forward with filing evictions after August 2023. But landlord companies that own properties with 50 or more units said they were more likely to file for eviction.

"Our surveys show that 71% of large landlords intend to evict, compared to just 39% of small landlords (1-4 units) and 40% of medium size landlords (5-50 units)," the study authors wrote.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.