How a hugely successful global treaty is delaying the first ice-free Arctic summer

An international treaty that banned harmful ozone-depleting substances has successfully postponed the occurrence of the first ice-free Arctic summer by up to 15 years, new research has found.

The Montreal Protocol, a UN treaty established in 1987 to protect the ozone layer, also addressed the issue of greenhouse gas emissions as ozone-depleting substances were also identified to be potent greenhouse gases.

New research, conducted by scientists from UC Santa Cruz, Columbia University and the University of Exeter, found that regulating these harmful gases contributed to the delay in global heating.

The far-reaching effects of this delay, including the mitigation of intense heatwaves, unpredictable weather patterns, sea-level rise, biodiversity loss and the release of methane resulting from melting permafrost, were highlighted in the study, published on Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study employed new climate model simulations to ascertain the impact of the Montreal Protocol on Arctic sea ice.

The researchers estimated that every 1,000 tonnes of ozone-depleting substance emissions that were curbed, prevented the melting of approximately seven square kilometres of Arctic sea ice.

“While ODSs (Ozone-depleting substances) aren’t as abundant as other greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, they can have a real impact on global warming,” said Dr Mark England, a senior research fellow at the University of Exeter.

“While stopping these effects was not the primary goal of the Montreal Protocol, it has been a fantastic by-product.”

Arctic sea ice melting is currently still at dangerous threat levels, while the first ice-free summer was projected to happen in the middle of this century depending on how quickly the world managed to cut down greenhouse gas emissions.

The positive side impact of the treaty, however, has turned out to be that the occurrence of this event has been delayed by 15 years.

“The first ice-free Arctic summer – meaning the Arctic Ocean practically free of sea ice – will be a major milestone in the process of climate change,” said professor Lorenzo Polvani from Columbia University.

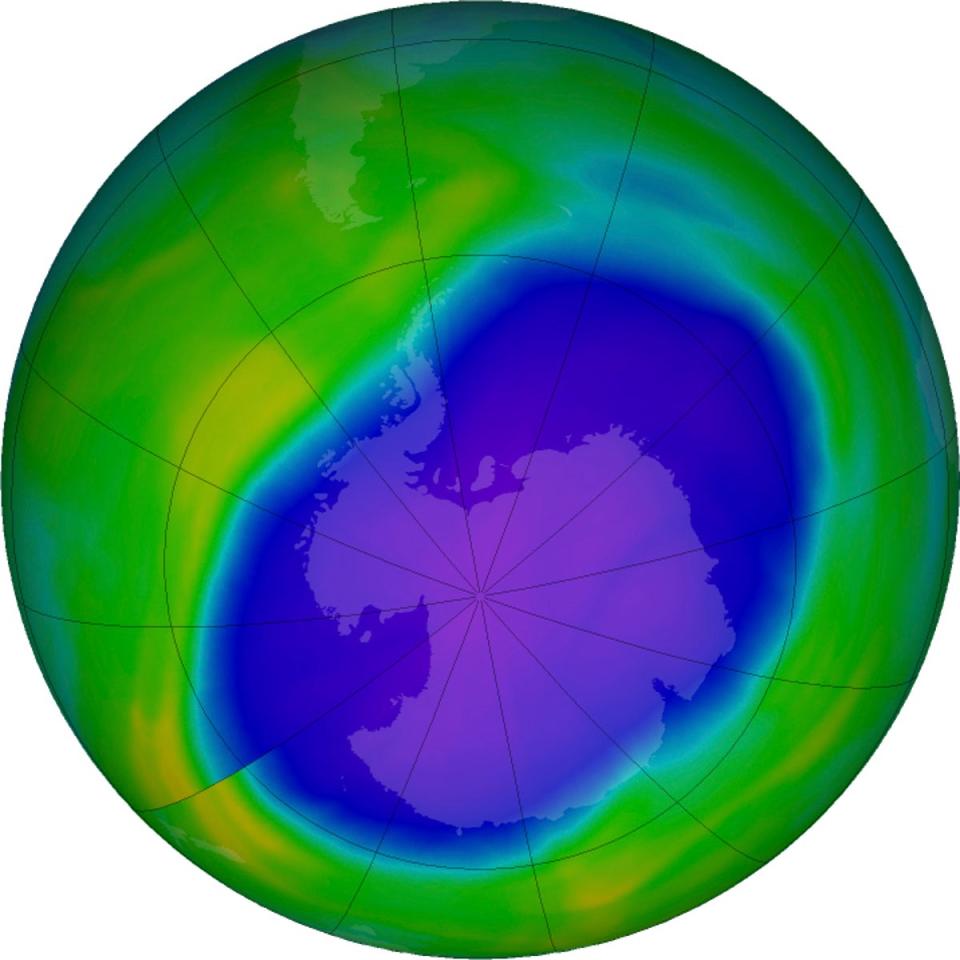

“Our findings clearly demonstrate that the Montreal Protocol has been a very powerful climate protection treaty and has done much more than healing the ozone hole over the South Pole,” he said.

“Its effects are being felt all over the world, especially in the Arctic.”

Ozone-depleting substances, including chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), were primarily used as refrigerants and propellants in industrial applications in the last century.

The discovery of a hole in the ozone layer was first announced by the British Antarctic Survey in May 1985. In response, 198 countries got together and signed the Montreal Protocol, leading to the regulation of these compounds to safeguard the ozone layer from harmful ultraviolet radiation.

As a result of these efforts, atmospheric concentrations of ozone-depleting substances have been declining since the mid 1990s, indicating the beginning of ozone layer recovery.

If current policies remain in place, the layer is expected to recover by 2040 to pre-thinning levels in 1980.

A recent study, however, also warned that harmful CFCs “are making a comeback”, continuing to increase in the atmosphere and reaching record highs in 2020.

Dr England also emphasised the need for continued “vigilance”.

He also said the opponents of the protocol predicted a range of negative consequences, “most of which did not happen”, and instead there are “numerous documented instances of unintended climate benefits”.

In light of recent predictions by scientists that global temperatures will surpass the critical 1.5C mark within the next five years, this research serves as a positive reminder of the significant achievements that can be made through coordinated global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.