How a heritage of Black preaching shaped MLK's voice in calling for justice

The name Martin Luther King Jr. is iconic in the United States. President Barack Obama mentioned King in both his Democratic National Convention nomination acceptance and victory speeches in 2008, when he said,

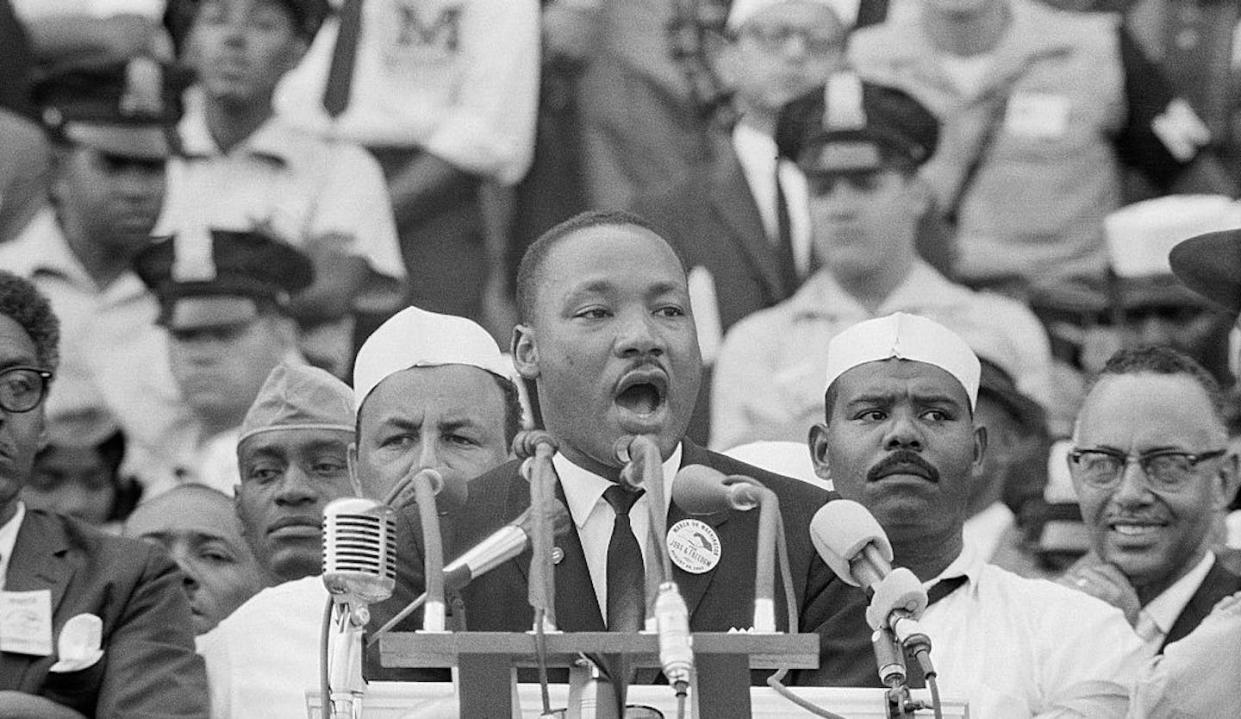

“[King] brought Americans from every corner of this land to stand together on a Mall in Washington, before Lincoln’s Memorial…to speak of his dream.”

Indeed, much of King’s legacy lives on in such arresting oral performances. They made him a global figure.

King’s preaching used the power of language to interpret the gospel in the context of Black misery and Christian hope. He directed people to life-giving resources and spoke provocatively of a present and active divine interventionist who summons preachers to name reality in places where pain, oppression and neglect abound. In other words, King used a prophetic voice in his preaching – the hopeful voice that begins in prayer and attends to human tragedy.

So what led to the rise of the Black preacher and shaped King’s prophetic voice?

In my book, “The Journey and Promise of African American Preaching,” I discuss the historical formation of the Black preacher. My work on African American prophetic preaching shows that King’s clarion calls for justice were offspring of earlier prophetic preaching that flowered as a consequence of the racism in the U.S.

From slavery to the Great Migration

First, let’s look at some of the social, cultural and political challenges that gave birth to the black religious leader, specifically those who assumed political roles with the community’s blessing and beyond the church proper.

In slave society, Black preachers played an important role in the community: they acted as seers interpreting the significance of events; as pastors calling for unity and solidarity; and as messianic figures provoking the first stirrings of resentment against oppressors.

The religious revivalism or the Great Awakening of the 18th century brought to America a Bible-centered brand of Christianity – evangelicalism – that dominated the religious landscape by the early 19th century. Evangelicals emphasized a “personal relationship” with God through Jesus Christ.

This new movement made Christianity more accessible, livelier, without overtaxing educational demands. Africans converted to Christianity in large numbers during the revivals and most became Baptists and Methodists. With fewer educational restrictions placed on them, Black preachers emerged in the period as preachers and teachers, despite their slave status.

Africans viewed the revivals as a way to reclaim some of the remnants of African culture in a strange new world. They incorporated and adopted religious symbols into a new cultural system with relative ease.

Rise of the Black cleric-politician

Despite the development of Black preachers and the significant social and religious advancements of Blacks during this period of revival, Reconstruction – the process of rebuilding the South soon after the Civil War – posed numerous challenges for white slaveholders who resented the political advancement of newly freed Africans.

As independent Black churches proliferated in Reconstruction America, Black ministers preached to their own. Some became bivocational. It was not out of the norm to find pastors who led congregations on Sunday and held jobs as schoolteachers and administrators during the work week.

Others held important political positions. Altogether, 16 African Americans served in the U.S. Congress during Reconstruction. For example, South Carolina’s House of Representatives’ Richard Harvey Cain, who attended Wilberforce University, the first private Black American university, served in the 43rd and 45th Congresses and as pastor of a series of African Methodist churches.

Others, such as former slave and Methodist minister and educator Hiram Rhoades Revels and Henry McNeal Turner, shared similar profiles. Revels was a preacher who became America’s first African American senator. Turner was appointed chaplain in the Union Army by President Abraham Lincoln.

To address the myriad problems and concerns of blacks in this era, Black preachers discovered that congregations expected them not only to guide worship but also to be the community’s lead informant in the public square.

The cradle of King’s spiritual heritage

Many other events converged as well, impacting Black life that would later influence King’s prophetic vision: President Woodrow Wilson declared U.S. entry into World War I in 1917; as “boll weevils” ravaged crops in 1916 there was widespread agricultural depression; and then there was the rise of Jim Crow laws that were to legally enforce racial segregation until 1965.

Such tide-swelling events, in multiplier effect, ushered in the largest internal movement of people on American soil, the Great “Black” Migration. Between 1916 and 1918, an average of 500 Southern migrants a day departed the South. More than 1.5 million relocated to Northern communities between 1916 and 1940.

A watershed, the Great Migration brought about contrasting expectations concerning the mission and identity of the African American church. The infrastructure of Northern black churches were unprepared to deal with the migration’s distressing effects. Its suddenness and size overwhelmed preexisting operations.

The immense suffering brought on by the Great Migration and the racial hatred they had escaped drove many clergy to reflect more deeply on the meaning of freedom and oppression. Black preachers refused to believe that the Christian gospel and discrimination were compatible.

However, Black preachers seldom modified their preaching strategies. Rather than establishing centers for Black self-improvement focused on job training, home economics classes and libraries, nearly all Southern preachers who came North continued to offer priestly sermons. These sermons exalted the virtues of humility, good will and patience, as they had in the South.

Setting the prophetic tradition

Three clergy outliers – one a woman – initiated change. These three pastors were particularly inventive in the way they approached their preaching task.

Baptist pastor Adam C. Powell Sr., the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZ) pastor Florence S. Randolph and the African Methodist Episcopal bishop Reverdy C. Ransom spoke to human tragedy, both in and out of the black church. They brought a distinctive form of prophetic preaching that united spiritual transformation with social reform and confronted black dehumanization.

Bishop Ransom’s discontentment arose while preaching to Chicago’s “silk-stocking church” Bethel A.M.E. – the elite church – which had no desire to welcome the poor and jobless masses that came to the North. He left and began the Institutional Church and Social Settlement, which combined worship and social services.

[ Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter. ]

Randolph and Powell synthesized their roles as preachers and social reformers. Randolph brought into her prophetic vision her tasks as preacher, missionary, organizer, suffragist and pastor. Powell became pastor at the historic Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem. In that role, he led the congregation to establish a community house and nursing home to meet the political, religious and social needs of Blacks.

Shaping of King’s vision

The preaching tradition that these early clergy fashioned would have profound impact on King’s moral and ethical vision. They linked the vision of Jesus Christ as stated in the Bible of bringing good news to the poor, recovery of sight to the blind and proclaiming liberty to the captives, with the Hebrew prophet’s mandate of speaking truth to power.

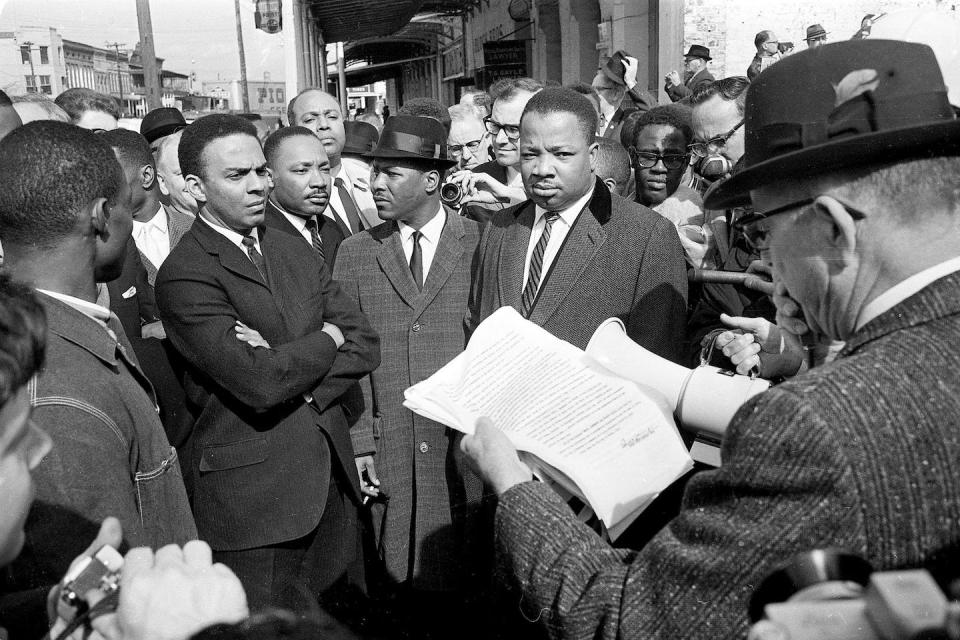

Similar to how they responded to the complex challenges brought on by the Great Migration of the early 20th century, King brought prophetic interpretation to brutal racism, Jim Crow segregation and poverty in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Indeed, King’s prophetic vision ultimately invited his martyrdom. But through the prophetic preaching tradition already well established by his time, King brought people of every tribe, class and creed closer toward forming “God’s beloved community” – an anchor of love and hope for humankind.

This is an updated version of a piece first published on Jan. 15, 2017.

Editor’s note: This piece has been updated to fix the year the U.S. entered into World War I, and to reflect changes in our style for Black.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Kenyatta R. Gilbert, Howard University School of Divinity

Read more:

Howard Thurman – the Baptist minister who had a deep influence on MLK

What activists today can learn from MLK, the ‘conservative militant’

Kenyatta R. Gilbert does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.