The first-ever Malta Biennale, where ancient history meets contemporary art

Strategically located at the crossroads between Southern Europe and North Africa, the small island of Malta has historically been a valuable outpost in the Mediterranean.

For centuries, it was conquered incessantly – starting with the Phoenicians in 700 BC, followed by the Carthaginians, the Romans, the Arabs, the Normans, the French and finally the British. In 1964, it won its independence and in 2004, became the smallest member state in the European Union.

A small but densely packed nation, Malta is rich in cultural heritage – with just over 300 square kilometres of land, it’s home to an astounding seven UNESCO World Heritage sites, including the earliest freestone standing buildings in Europe.

This spring, Malta is seeing a new wave of culture hit its shores, as it invites dozens of contemporary artists from around the world to create site-specific artworks for the first-ever Malta Biennale.

Eighty artists from 23 countries were invited to exhibit work at the event, which runs until 31 May and takes place in more than 20 different venues across the country. The goal, according to the head curator, is to carve out a unique place in the contemporary arts calendar.

“The idea is to use Malta as an observatory to address what is going on in the Mediterranean,” said the Biennale’s Artistic Director Sofia Baldi Pighi.

“I really think it’s important that the museum and the exhibition can be a place where we can exercise our critical thinking,” she told Euronews Culture. “The goal is not to give any answers about these very big problems. Our role as art workers is to raise questions and offer a safe space to be able to do that.”

A dialogue between past and present

The Biennale tackles difficult contemporary issues – like identity, migration, decolonisation and the legacy of patriarchal societies – through a series of themed pavilions across Valletta, Cottonera and Gozo.

It transforms some of the country's most emblematic sites: The Grand Master’s Palace in Valletta, the seat of Malta’s presidency, is repurposed through works that reimagine the transmission of collective memory through a feminine lens.

The incredible Ġgantija Archaeological Park, with its mystical megalithic ruins dating back to 3600 BC, is juxtaposed with Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama’s “Garden of Scars,” a collection of concrete slabs and casts of tombstones intertwining the histories of Ghana and the Netherlands.

Valletta’s Main Guard, once off-limits to Maltese and reserved exclusively for British colonial soldiers, becomes a refuge for questioning the effects of colonialism on Maltese identity.

On their own, the works contemplate important contemporary issues in creative new ways. But their thoughtful placement by the curatorial team elevates the exhibition to something greater than the sum of its parts.

Belgian artist Sofie Muller’s installation “The Clean Room,” for example, takes on new meaning in Malta’s National Museum of Archaeology – her contemporary works sharing space with some of humanity’s oldest sculptures.

Muller’s series, which she began working on in 2017, explores the idea of the “perfect baby” through a collection of lifelike newborns carved from varying shades of alabaster.

The infants’ bodies emerge from the stone, but Muller leaves some pieces of the stone raw, blemishes on their otherwise immaculate figures.

“It’s a wonderful dialogue,” Muller told Euronews Culture at the opening of the Malta Biennale. “Of course there is a link, because my work questions fertility and pregnancy and gynaecological techniques. And there you can see the first sculptures from 5000 years ago, examining many of the same questions. It’s amazing to bring them together.”

Muller’s installation is also a mirror for visitors, who see in her sculptures their own lived experiences. A disclaimer outside the room where Muller’s installation is located warns that the artworks may be disturbing for some.

In this context, Muller’s installation inadvertently becomes a statement on abortion. Malta has the strictest abortion laws in the European Union, with all abortions considered illegal except if the mother’s life is in danger.

War in Gaza front and centre

Unlike many recent cultural events, which have struggled to meaningfully discuss the war in Gaza, the Malta Biennale openly addressed it, with several participating artists’ works offering support to Palestinians.

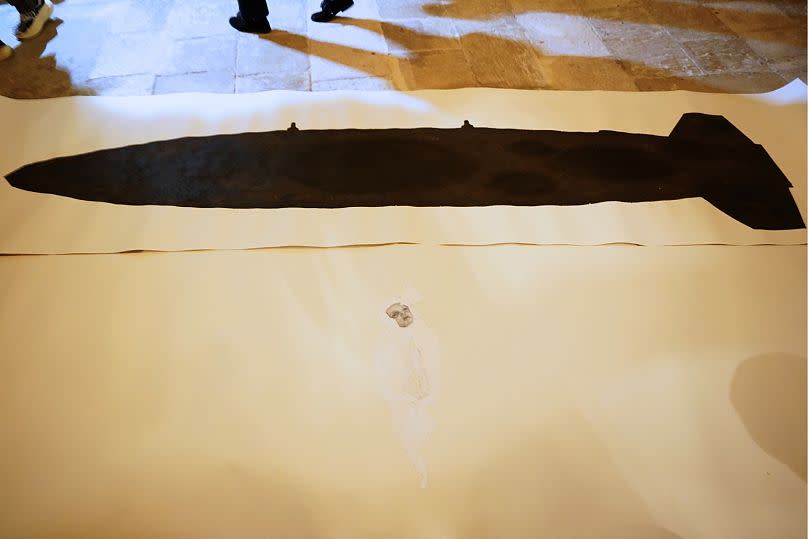

One of the most powerful pieces addressing the war is by US artist Mel Chin, who unveiled a surprise last-minute addition to his Biennale entry on 13 March. He completed the diptych upon his arrival in Malta, unpacking it on-site as he explained his thought process.

The two scrolls – which hang on top of one another – feature true-to-size depictions of five month-old Palestinian victim Muhammad Hani al Zahar and the US-made Mark-84 bomb that is believed to have killed him.

“Satellite imagery claims that hundreds (of these bombs) were dropped in Gaza during this period. It’s most likely what caused the destruction of Mohammad as well as many babies in Gaza,” Chin told a small room of journalists as he unrolled the scrolls in Gozo.

To make the painting of the bomb, Chin used soil from his studio in North Carolina, which he said was initially a birthing hospital for children.

“This weapon creates craters approximately 60 metres wide, and you only know they dropped it because you see the earth removed. So using earth to create the piece was necessary,” he explained.

On Instagram, he said he was “determined to memorialize the innocent victims of the ongoing atrocities and make note of the American complicity in the weaponization of the Israeli Defense Forces.”

He also thanked the curatorial team for their “patience and trust,” at a time where “suppression and censorship of artists is pronounced”.

Baldi Pighi also used her platform to clearly state her position on the war. In her speech at the opening ceremony of the Biennale, which was broadcast live on Maltese television, she received resounding applause as she called for a ceasefire in Gaza.

“That’s the point of art, to be controversial, to create discussion, to create debate,” she told the audience, including artists, journalists and Maltese politicians. “That is why we need artists in our democracies.”

Baldi Pighi told Euronews Culture that she benefited from the fact that Malta is one of a handful of EU members that recognises Palestine as a state.

“This helped me as a curator by giving me freedom to address this topic,” she said, using the word “genocide” to qualify the Israeli killing of Palestinians in Gaza.

Art for the people

On top of making sure no topics were off limits, Baldi Pighi said it was important to make sure the Biennale could reach the largest number of people, especially those who may be intimidated by contemporary art.

The Malta Biennale public programme includes free weekly activities including roundtable talks, workshops and performances. The goal is to get the local community involved and make contemporary art more approachable for everyone.

“The idea is to think of the exhibition not just as a final end but also as an activator,” Baldi Pighi said. “We’re doing our best to push the Maltese community to be here.”

Many of the events take place in public spaces, which can lead to a clashing of cultures. During the press preview, the confrontation between artists and the general, unsuspecting public was at times humorous.

“Is that man part of the performance? I f***ing hope he is,” one of the artists exclaimed with genuine outrage, as an unbothered old Maltese man pulled out of his parking space along the Cottonera docks, interrupting a performance by artist Andrea Conte where six people carried flags of the Mediterranean from the docks to the armoury.

The performance was a site-specific iteration of Conte’s “Displacement” series, which comments on forced climate migration.

Another performance, by Franco-Maltese duo Keit Bonnici and Niels Plotard, involved an artist washing a red telephone booth in the centre of Valletta and then wrapping it as if it were going to be shipped somewhere.

“Once ‘wrapped’, we are faced with a number of questions - where has it been? Has it just arrived? Where did it come from? Is it going somewhere? Where is it going?” a posted description of the work explains.

The performance is meant to raise questions about the British colonisation of Malta and the legacy it left behind. Curious tourists stopped to watch, perplexed by the crowd of journalists and artists staring at a man washing a phone booth.

“Why are they all standing there?” one man asked his partner.

“I think it’s some sort of art installation,” she answered, half rolling her eyes, before heading to read the description.

For Baldi Pighi, these types of interactions are exactly what she hopes will arise from the Biennale.

“A lot of people are scared, and I understand, because contemporary art can sometimes be very elitist and can exclude a lot of people,” she said.

“If the audience doesn’t get something, it’s never a problem of the audience, never a problem of the artist, but it’s a problem of mediation.”

That’s the beauty of designing a first edition, she said. There are endless possibilities to reinvent and reimagine the concept of a Biennale.

“When you have a white canvas in front of you, it can become very different things,” she said. “That’s why I asked myself, do we need another Biennale? And if so, how do you make it relevant? This is why the public programme has become central, and also creating this community between artists so we can share ideas, share a project.”

“That’s the idea, that this could be a starting point for something else – something we can’t even imagine yet.”