Experts blast CDC over failure to test sewage for signs of H5N1 bird flu virus

It emerged as a powerful tool for public health officers during the COVID-19 pandemic, when it was used to gauge the prevalence of coronavirus in communities across the nation.

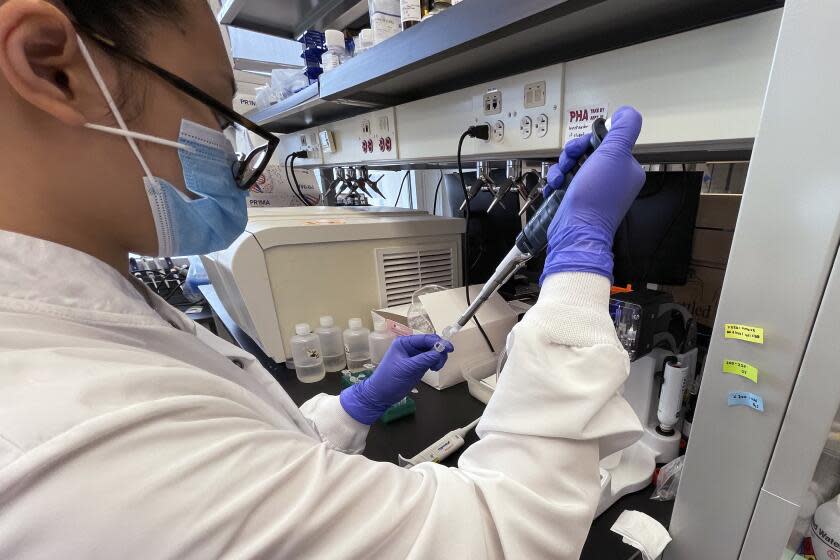

But wastewater surveillance — the testing of sewage for signs of pathogens such as SARS-CoV-2, poliovirus and mpox virus — has yet to be employed in the tracking of H5N1 bird flu virus.

Now, as officials attempt to determine the extent of bird flu outbreaks among dairy herds, some experts are urging that wastewater surveillance begin immediately. Others are faulting the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for reportedly discouraging its use.

Read more: 'Nobody saw this coming': California dairies scramble to guard herds against bird flu

“It has been consistently demonstrated that wastewater surveillance only enhances traditional surveillance, and often outperforms it when it comes to early/timely outbreak or surge detection,” said Denis Nash, distinguished professor of epidemiology and executive director of City University of New York's Institute for Implementation Science in Population Health.

“In this case, since traditional surveillance is not really systematically occurring, and wastewater surveillance is relatively low-cost and easy to implement, it makes a lot of sense to me to go ahead and deploy it strategically,” said Nash, whose team developed New York City’s community-based wastewater surveillance for SARS-CoV-2.

That has not been the view of the CDC, however.

Recently, Marc Johnson, a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the University of Missouri, said he was told by the agency not to use a virus assay he'd created for the purpose of tracking H5N1 outbreaks. The reason? Johnson said officials told him it would just add to the confusion.

Johnson said that if the assay had been in widespread use earlier this year, the spread of bird flu through the nation's dairy herds could conceivably have been stopped, or at least slowed down.

"I always think the more information we have, the better," he said.

However, he said he did understand the government's rationale.

"Public health does not like ambiguous information," he said. "You get a positive, you don't know if that's from a cow or a bird. Or maybe from milk poured down the drain."

The CDC did not respond to questions from The Times.

Read more: California wildlife is vulnerable to an avian flu ‘apocalypse.’ What is driving the spread?

Concern over the virus escalated in March, when federal officials announced the discovery of avian flu in a Texas dairy herd. Over the next few weeks, reports of the virus in other states began to pop up. It also showed up in barn cats that drank raw milk, and in one dairy worker.

H5N1 bird flu has now been detected in 36 herds across nine states, and health and U.S. Department of Agriculture officials are scrambling to determine its reach. They believe the virus was introduced by a wild bird — either via contact or feed — at a Texas farm in December, giving the virus months to travel to other herds and animals.

The virus was also found in one of five grocery-shelf milk samples tested by federal researchers. Those samples showed the virus had been inactivated by pasteurization, reducing the health threat to people.

In California, where the virus has yet to be detected in dairy cows, wildlife officials are keeping a wary eye on migrating wild bird populations as well as domestic poultry and farm animals.

Eric Topol, a professor of molecular medicine at Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, said the CDC is "off base" to say wastewater surveillance would cause confusion.

"If anything, we need to track the spread of the virus and its evolution, which isn’t getting done well by USDA and CDC," he said.

Michael Payne, a dairy educator and researcher at the University of California’s School of Veterinary Medicine, agreed with that sentiment. Although he was not familiar with the assay Johnson devised, he said an accurate test would be valuable.

"Such a wastewater assay could be a useful tool, even given the uncertainty of exactly where the virus was coming from," he said. "There is a growing body of literature that is using PCR testing in wastewater to measure pathogens of public health interest."

Nash, of CUNY, said he’d advocate for a “strategic deployment of community-based and facility-based wastewater surveillance.”

He said testing wastewater at hospitals and health clinics would provide clear signals if an outbreak were to occur. Starting testing now, when a baseline for other "confusing" elements such as contaminated milk and bird droppings could be established, would help quell that noise.

He said that in the current situation, “we need reliable early warning because if community spread did happen, every additional day of notice would matter a great deal in terms of potential lives saved.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.