What I teach Harvard Law School students about opening arguments

Though Hollywood movies about courtroom dramas often glamorize the closing arguments given by lawyers, in reality the opening statement is likely the most important single event of a trial.

Lawyers in the hush money case involving former President Donald Trump and alleged payments to porn star Stormy Daniels presented their opening statements on April 22, 2024, in New York.

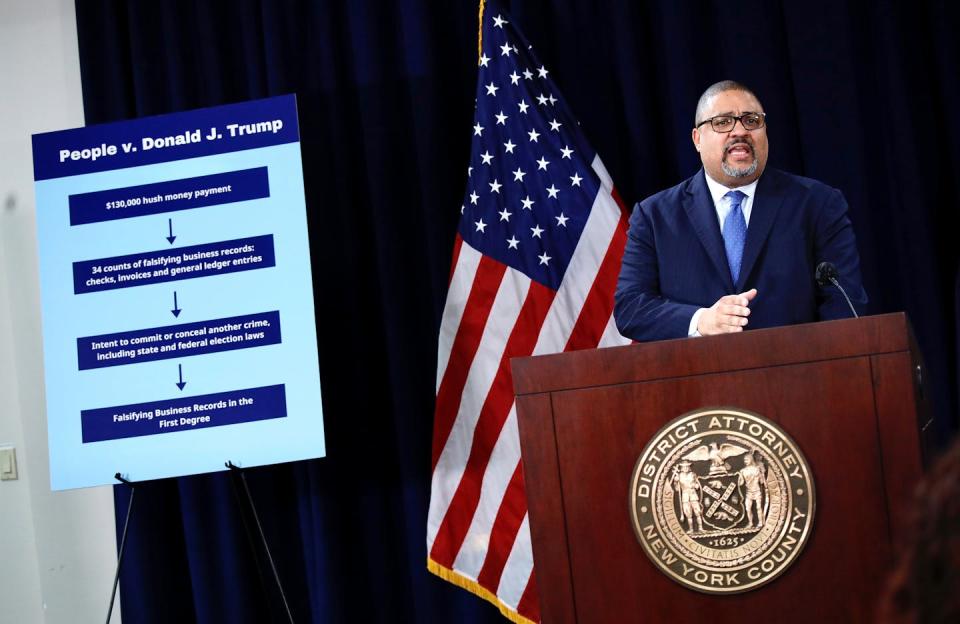

In this case, Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg charged the former president with 34 felony counts of falsifying business records as part of an effort to influence voters’ knowledge about him before the 2016 presidential election. Trump entered a plea of not guilty.

Academic psychologists tell us that between 65% and 75% of jurors make up their minds about a case after the opening statement. What’s even more incredible is that 85% of those jurors maintain the position they formed after the opening statement once all evidence is received and the trial is closed.

More often than not, it is too late by closing arguments to win over the jury.

This phenomenon comes as no surprise to veteran trial lawyers. They are aware of two theories that define how jurors – indeed, people generally – process information: the concepts of primacy and recency

These ideas suggest that jurors best remember what they hear first and what they hear last. It is vitally important, then, for lawyers on both sides to start their opening arguments with a bang.

The psychology of jurors

I have taught a course on trial advocacy for the past two decades at the Harvard Law School. Part of my curriculum is to teach budding lawyers how to deliver effective opening statements.

If the idea is to win over the jury by the end of the lawyer’s opening statement, how, in practice, is that done?

Trial lawyers steeped in the research know that juries respond to a well-considered theory of the case, punctuated by a pithy theme.

A theory of the case is a brief, three- to five-sentence statement akin to what is known as an “elevator pitch.” The theme is a short, pithy summary of the theory of the case that is easy for a juror to remember. Often the theme is the first sentence out of the lawyer’s mouth, followed by a fuller description of the theory.

Indeed, in my class at Harvard, the very first skill I teach is how to develop theories and themes. In order to effectively convey a theory in a case, many lawyers start their opening statements with “This is a case about …” and then fill in the specific details.

For example, the prosecution in a murder case may start their opening like this:

“Members of the jury, this is a case about the death of an innocent young woman, witnessed by concerned citizens, who all identify the only person with a motive to kill her, the defendant.”

In stark contrast, the defense might start with something that is the complete opposite of the prosecution’s opening statement:

“Members of the jury, this is a case about a jealous ex-lover who shot a woman in cold blood, fled the country and left my client to take the fall.”

In each example, the jury is given enough information to frame the evidence they will hear throughout the trial.

After both sides have finished their openings, data shows that more than two-thirds of the jury will have come to a decision that will persist through the remainder of the trial.

Why do juries tend to behave this way?

Research also has taught trial lawyers that if you connect the jury with your theory of a case, at the beginning of the trial, jurors will process all the rest of the evidence – whether potentially helpful to the prosecution or to the defense – through the prism of that theory.

The importance of opening statements cannot be overstated. They set the tone and offer the jury a framework to understand the upcoming months of testimony they are about to hear.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Ronald S. Sullivan Jr., Harvard University

Read more:

Ronald S. Sullivan Jr. does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.