Europe Greens Fight to Save the Climate Plan They Helped Launch

(Bloomberg) -- Barely two years ago the European Greens were riding high, negotiating a policy package to create the first climate-neutral continent by 2050 after their strongest-ever electoral performance. Then Russia invaded Ukraine.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Trump Pledges Across-the-Board Tax Cuts If He Returns to Office

Ice Cube’s Big3 Basketball League Sells Its First Team in $10 Million Deal

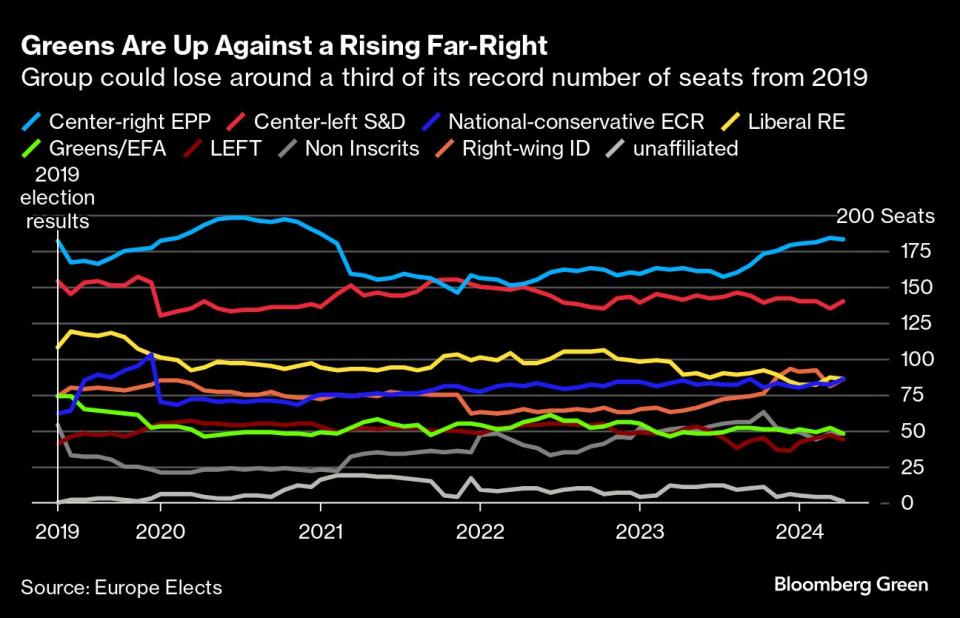

The ensuing energy crisis exacerbated a cost-of-living crunch for Europe’s citizens who had barely recovered from the Covid-19 pandemic. The fallout has put the Greens on course to lose a third of their seats at next month’s European parliamentary elections. Surging support for climate skeptical right-wing political groups leaves the future of the landmark Green Deal uncertain, even though over 50 laws have been passed over the last three years.

“What we started in 2019 was of course a transformation of our entire economy — we started the marathon in 2019 and we are now probably five kilometers into it,” Bas Eickhout, the Greens’ lead candidate, told Bloomberg Green’s Zero podcast. “The wind has changed, there is more resistance.”

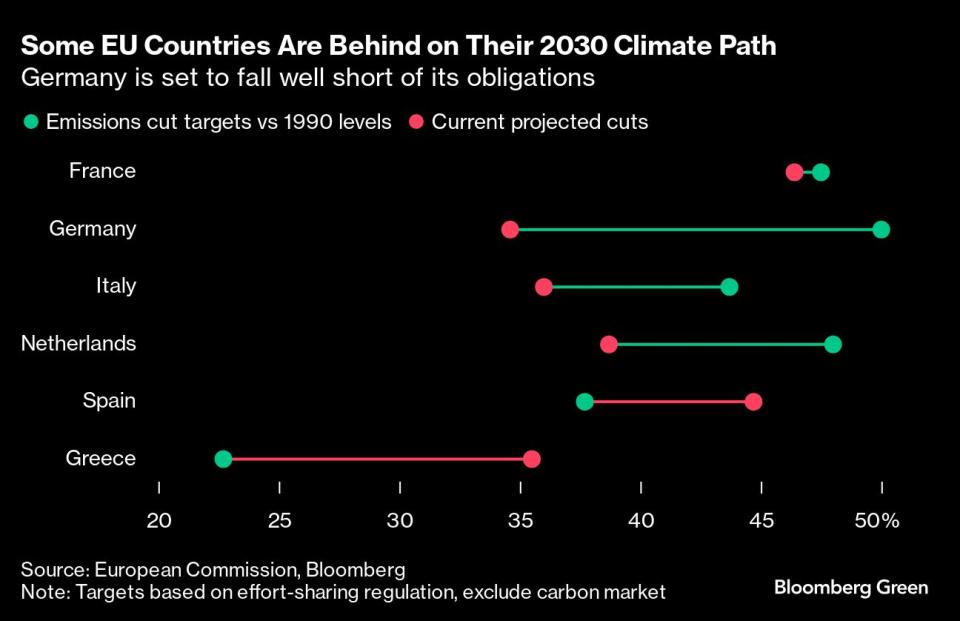

The question is whether Europe can maintain its ambitious green targets without losing competitiveness. Some analysts have pointed to the growing popularity of far-right parties — for example, those linked to Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and French Presidential hopeful Marine Le Pen — as evidence of a backlash against the EU’s efforts to cut emissions by 55% by 2030.

Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, who relied on support from the Greens last time round, is turning increasingly toward the right to help secure a second term. Europe’s former climate czar, Frans Timmermans, has said that the issue of stopping climate change is now part of the “culture wars.”

Europe’s industry, scarred by the energy crisis, has called for “corrective measures” on swathes of environmental regulation it says risks pushing businesses out of the region. Citizens are becoming aware that the transition will directly affect their lives, from the type of car they drive to how much they have to insulate their homes. Farmers have driven into Europe’s capitals in tractors to protest what they see as punishing bureaucracy that puts their livelihoods on the line.

“We have had to deal with a regulatory tsunami in agricultural matters with the policies arising from the Green Deal,” Christiane Lambert, President of the farming lobby Cogeca, said during a launch of the group's election manifesto last month. “We want less regulation but better ones.'”

More seats means more power to sway the agenda of the commission, the EU’s executive branch, where post-election horse-trading between member states and political groups determines who takes which post. Progressives are worried that von der Leyen’s pivot to the right could mean that, at best, green policies are put on the back burner. A worst case scenario could see them watered down, with some of the most hard-hitting policies, like a carbon border levy and an expansion of carbon markets onto road transport and heating, still to come.

Laws that are already in place, such as phasing out the combustion engine in new cars by 2035, are set to be reviewed in the coming years. While the trajectory is fixed, there may be more flexibility introduced on how to get there depending on the ferocity of opposition.

Whatever form the next European Parliament takes — and there are signs support for the far right is plateauing — there is broad approval of an EU industrial strategy that moves beyond the rather toothless Net-Zero Industry Act, which was rushed through as a response to the US Inflation Reduction Act. But it’s less clear what it will look like.

“It’s going to be difficult to win this subsidy race,” Eickhout said. “We are only going to develop a credible carrot for industry if there is a credible European strategy behind it.”

The Greens are also calling for an EU-wide tax of up to 3.5% on the top 0.5% of wealthiest individuals, while ending almost 500 million euros of fossil fuel subsidies so it can channel those funds into an industrial strategy. The group also wants the climate neutrality target to be brought forward by a decade, to 2040. The power to make such changes will be slim even if it holds onto the seats it won last time round.

Recently, several elements of the Green Deal aimed at restoring nature and cutting pesticides have been dropped in a bid to appease farmers. Eickhout worries about such concessions, arguing that the energy transition will be a fundamental part of the EU’s competitive advantage in the coming years. His party wants to create a Green and Social Transition Fund worth 1% of the region’s economic output to support green industries and prepare citizens for the transition.

“The green agenda is probably the best agenda for the future of our industry,” Eickhout said. We “are the better ally of industry than what conservatives claim to be.”

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.