How did police miss Brian Lush's body? Human error — or policy gaps — may have played a role

It sounds like the start of a true crime documentary: a search for a missing man ends with his body found in the trailer of a truck. The twist, of course, is that the missing man had been driving that truck — and it's precisely where he was last spotted alive.

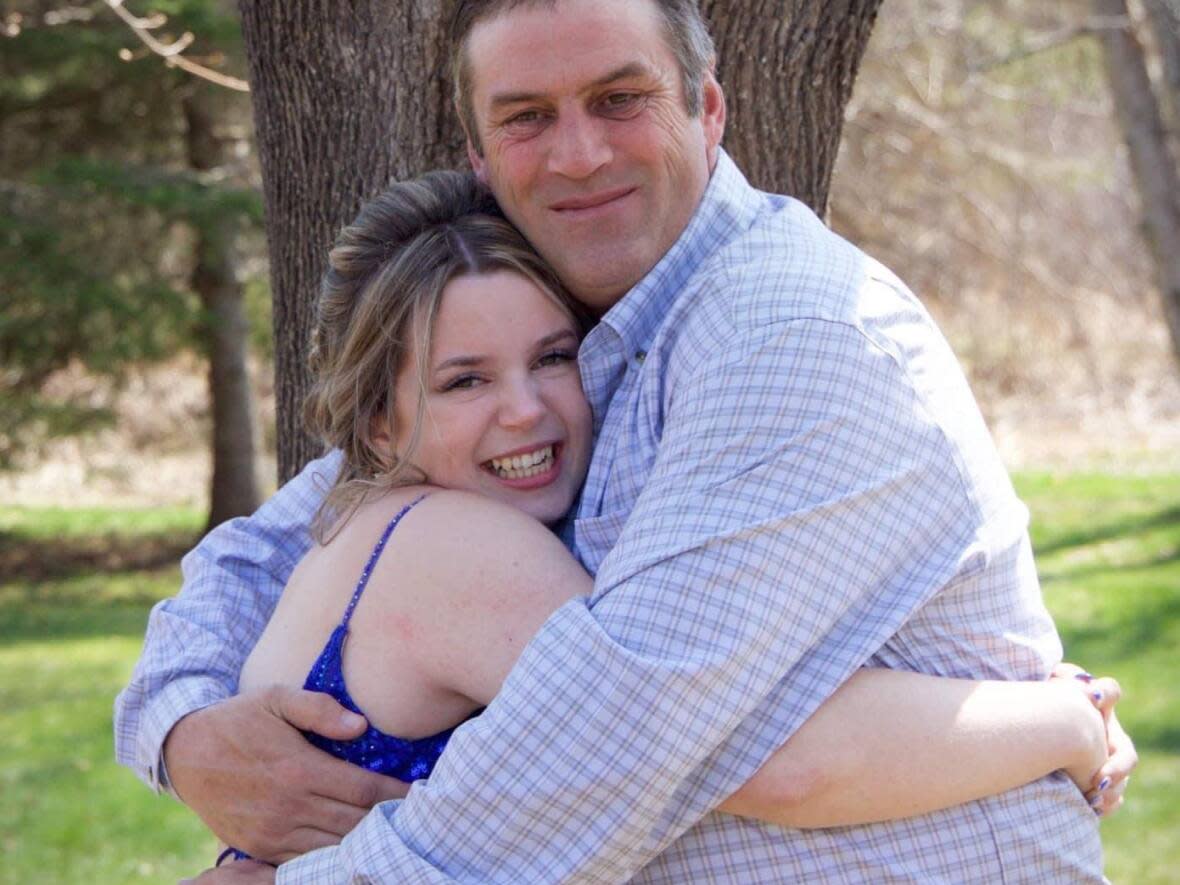

For Brian Lush's family, it's a bizarre tragedy that they're now forced to cope with, after the remains of the 51-year-old trucker were discovered in his rig's trailer in Port aux Basques, N.L., on the truck's way back home from Ontario.

Lush was last seen around his rig at a gas station in Summerstown, Ont., on April 24. Ontario Provincial Police investigators said at the time that security video showed Lush walking around the side of the truck and out of frame.

The OPP says they led an intense search for Lush for the next two weeks, one that involved dog teams, drones, helicopters and search and rescue experts.

But they appear to have somehow missed Lush's body, right where he'd last been spotted.

Details about the case are scarce, as it remains under investigation, but the Ontario police force and the Newfoundland and Labrador RCMP say they don't suspect foul play. It's not clear where in the trailer Lush's remains were found, or whether the trailer was thoroughly examined before it crossed the Ontario border on its way back east to Newfoundland.

OPP spokesperson Bill Dickson said Friday the force won't be releasing any other details about the case. "We prefer to provide any additional information to the family," he wrote in an email.

Former police officer Dan Salomons knows just as much about this case as the public: very little. But if he had to guess, based on his own experience investigating missing persons cases, human error could have come into play.

"On the surface, it doesn't look good," Salomons said, in an interview in his home office.

"But that being said, I've been involved in a number of investigations, homicide, whatever it is, that on the surface it doesn't look like we're doing a good job or we're not doing as much as we possibly could. But we as investigators have information that we can't release to the public, because it would compromise an investigation."

Salomons was an officer for 13 years with the Peel Regional Police in Mississauga. The first thing any police officer does, he says, is search — thoroughly — the area where the person was last seen.

"Any time that I have done a missing persons investigation, there is … a pre-recorded checklist that you have to go through and just check all the boxes to complete the missing person report," Salomons said.

One of the first standard places to look is the area they were previously in.

He'd often find children hiding in strange places inside their own homes, for instance — uncovered only because officers would leave no stone unturned.

But mistakes happen. It's possible an officer simply couldn't see Lush or his remains among any cargo that may have been inside. Front-line constables on the scene then might have checked that trailer off the list, marking it as cleared. And with time of the essence, Salomons says, the search would have rapidly expanded in hopes of finding him alive.

"If I had to guess, that would be it, that somebody opened up the back trailer. Maybe they're not familiar with transport trailers and all the nooks and crannies and hiding spots or whatever there is, and they thought that they did a thorough enough search of the truck by opening up the back door," he said.

Whatever happened, Salomons recalls the frustration of not being able to find someone who's vanished. Sometimes all the training and digging a police force can muster still leaves detectives empty-handed.

"I do believe that the training and the structure that's laid out already is sufficient and relevant," he said. "But that's not to say that human error is impossible."

The one regret of his career, he says, is the case of a missing woman who to date has never been found. He gets visibly upset as he recounts how the force even deployed undercover officers in an attempt to locate her.

"It's a very strange thing that somebody can just disappear and you can't find the information, the evidence to find them," he said slowly.

"It's not a good feeling, that's for sure."

Maureen Trask has experienced Salomons's frustration from the other side.

The Puslinch, Ont., woman lost her 28-year-old son in 2011. His car was found in an area of northern Ontario he would frequent, 13 days after she filed a report with the Waterloo Regional Police Service.

The OPP then took over her case. And for a long time, she struggled to get any communication from the officers on his case, she said. Her son's remains weren't found until 2015.

She's heard the same from other grieving families.

"I've seen the system and you know, I tell families police are the ones accountable for searching and investigation. That's their role," she said. "So don't try and take it on, but do push for answers."

Trask has been advocating for changes to missing persons policy ever since. She lobbied for Ontario to adopt a law that grants police sweeping powers to investigate when someone disappears.

The Missing Persons Act in Ontario has been a vital tool for officers, she says. "They say, 'Maureen, it's remarkable how quickly we can get information now,'" Trask said.

"It's helping them get access to that information and search locations where the individual may have last been seen, which again, they couldn't do before."

But people are still falling through the cracks, and she suspects the lack of national standards plays a role.

"Every jurisdiction does things differently. There is no standard across the board to say, if a case is moving from one place to another, 'here's what information has to be shared at a minimum,' because there is no law saying one jurisdiction has to share their investigative information with another, which to me is absurd," she said.

"There's a lot of gaps. And what we need across Canada … is to have minimum standards when it comes to missing persons reports and procedures and investigation expertise."

Trask will keep pushing for a formal training curriculum and some kind of national system to regulate how missing persons cases are handled. It's too easy for them to remain in the shadows otherwise, she says, their files growing cold.

"The government does not acknowledge missing persons as a social issue, or anything that requires anyone's attention other than police," she said.

"It's sad. It's really sad."

Download our free CBC News app to sign up for push alerts for CBC Newfoundland and Labrador. Click here to visit our landing page.