Crown declines to lay charges against Edmonton police officer who fatally shot unarmed man

An Edmonton police officer won't face charges for fatally shooting an unarmed man in 2021, despite Alberta's police watchdog finding reasonable grounds that the officer committed a crime.

The Alberta Serious Incident Response Team (ASIRT) investigation concluded there are "problematic" pieces about the officer's account of what happened.

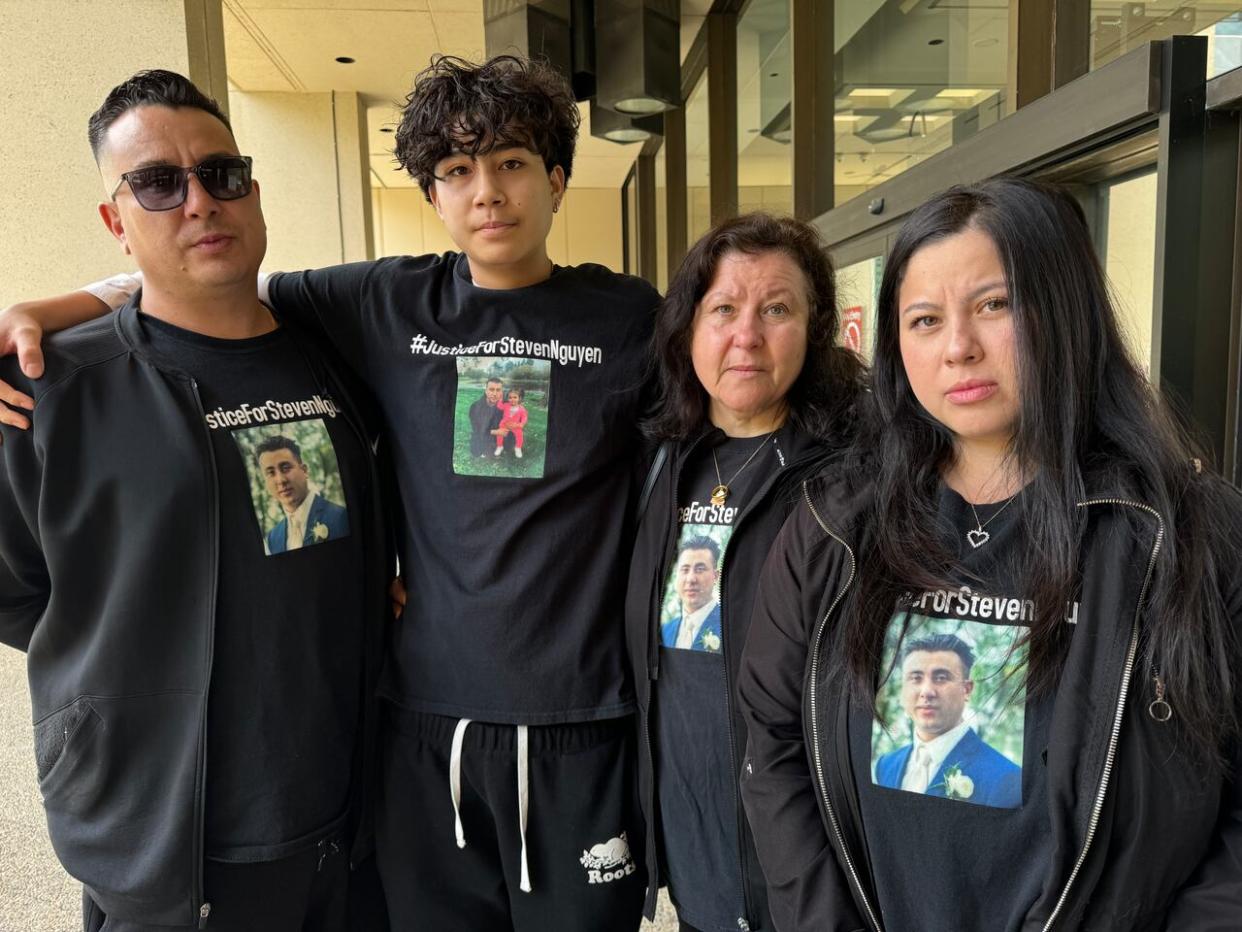

The family of Steven Nguyen identified him as the 33-year-old man who was killed in the north-central Rosslyn neighbourhood on the night of June 5, 2021. They've filed a lawsuit against the Edmonton Police Service, and the officer who shot Nguyen, who is identified in court documents as Const. Alexander Doduk.

The officer shot Nguyen four times "within seconds" of encountering him, according to the ASIRT report, released Wednesday.

"In this case while [the officer] subjectively believed that it was reasonable to shoot [Nguyen], objectively this belief is lacking," ASIRT executive director Michael Ewenson wrote in the report.

Doduk and his EPS partner were responding to a report from a resident who said he saw a man with a weapon that looked like a screwdriver or a knife.

The man who called 911 described the person he saw acting erratically, but not aggressively. A toxicology report later showed Nguyen had methamphetamine in his system at the time.

Steven Nguyen was fatally shot in Edmonton's Rosslyn neighbourhood on the night of June 5, 2021. (Submitted by Melisa Solano)

The agency referred the case to the Alberta Crown Prosecution Service to consider a culpable homicide charge, but after a review, the Crown won't pursue a criminal case.

In a statement to CBC News, an ACPS spokesperson said the Crown prosecutor who assessed the case determined it couldn't be proven that the officer's actions were unreasonable.

"In hindsight, the perception of the constable was mistaken, and the result was tragic, but the action taken could not be proven to be criminal."

Nguyen's family members said Wednesday the decision left them shocked.

"What happened to him was not right. It was not fair. … We want the public to be aware of what is happening," Nguyen's sister Melisa Solano said.

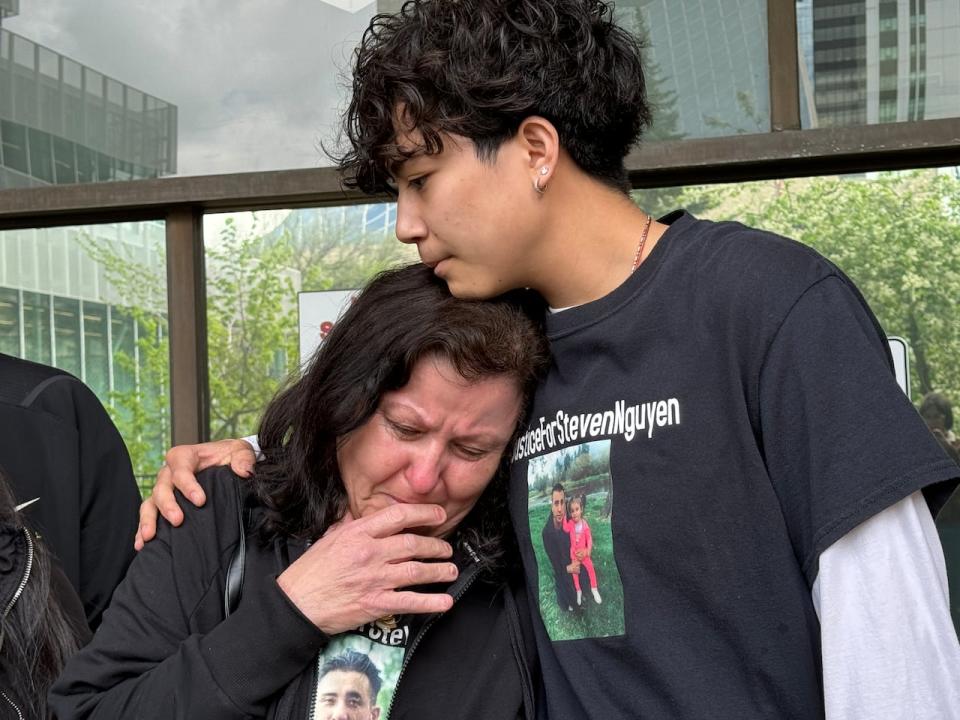

Maria Nguyen leans on her grandson Christian Nguyen as she speaks about her son, Steven Nguyen, who was shot and killed by a police officer in 2021. (Madeline Smith/CBC)

His brother, Chris Nguyen, said the family plans to keep seeking justice.

"Nobody deserves to die from the people that are supposed to protect and serve our community."

Doduk is facing assault charges in an unrelated case, and is scheduled to go to trial next year. According to an EPS spokesperson, he's currently on unrelated paid leave.

Details of the investigation

Doduk refused an interview with ASIRT investigators, but he provided his police report and notes. He wrote that Nguyen was reaching into his pocket despite commands to stop, and he pulled out a "black rectangular object" that the officer believed was a gun.

The object was actually a cell phone, the ASIRT report says.

A photo of the phone that Steven Nguyen was carrying the night he was killed is included in the ASIRT report investigating his death. (ASIRT)

A blue barbecue lighter was also in Nguyen's pocket, which the report says could have been what the person who called 911 mistook for a weapon.

"No weapon of any sort was located on [Nguyen], and [the officer's] justification for shooting is that an item resembling a firearm was pointed at him in poor lighting conditions," Ewenson wrote.

According to the ASIRT report, a senior officer showed up after the shooting and told Doduk to leave the scene, but Doduk returned and took a photo of the phone found near Nguyen on the ground.

Ewenson wrote that Doduk's subsequent description of what he felt was a firearm "may be purposely tailored to fit the description of his photo of the phone."

Doduk's notes also repeatedly describe Nguyen being "engulfed in shadow" on the residential street where the officers found him past 11 p.m., with trees and bushes blocking the nearby streetlights and making it difficult to see.

Part of the ASIRT investigation included a recreation of the lighting conditions at the scene, finding they were "markedly better" than Doduk claimed.

The officer also said he didn't use his flashlight, but video from an EPS helicopter "captures a discarded and operational flashlight on the ground in close proximity to where [he] would have been standing when he fired the shots."

Lawyers call for transparency

Samantha Labahn, one of the lawyers representing the Nguyen family in their civil suit, said the Crown's decision not to lay charges in the case is "perverse."

"The Alberta Crown's refusal to explain itself most importantly to the Nguyen family, as well as Steven's loved ones, is reprehensible," she said.

"To make matters worse, we have no way to scrutinize it. … We're left wondering, why did the Crown make that choice?"

The ASIRT report says the agency received an opinion from the Crown about whether charges should be laid. The ACPS told CBC News that opinion won't be publicly provided because it's privileged, and therefore confidential.

Ewenson notes that ASIRT and the Crown are bound by different standards when they assess cases, and that can result in different outcomes.

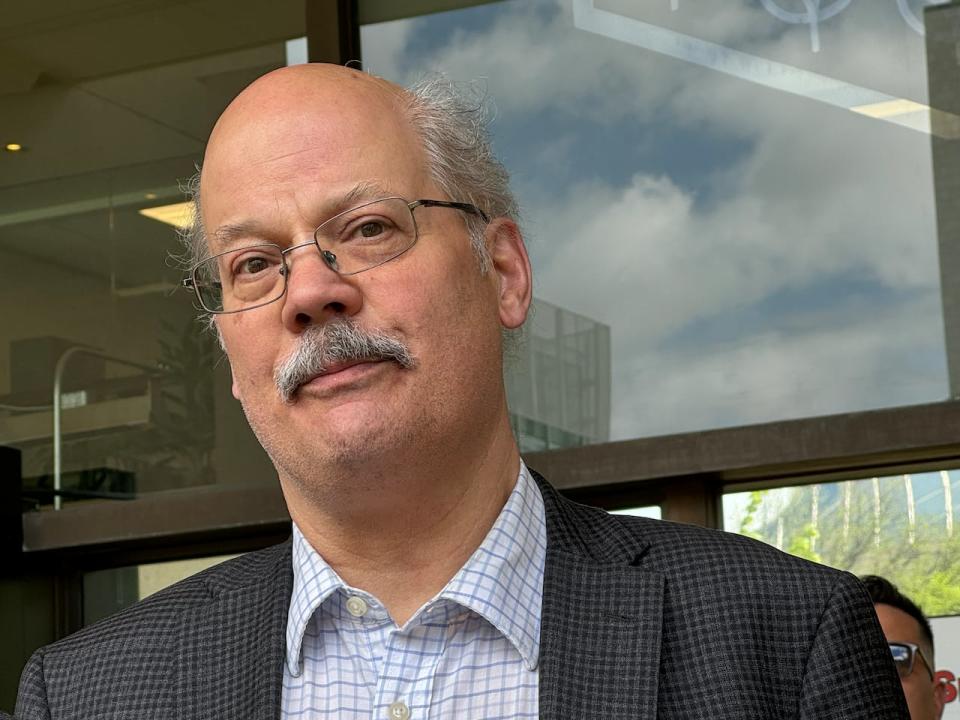

Defence lawyer Tom Engel is one of the lawyers for the Nguyen family in a civil lawsuit. (Madeline Smith/CBC)

The decision follows two recent Edmonton-area cases where the Crown declined to prosecute police after ASIRT concluded charges should be considered.

In March, the ACPS didn't pursue a criminal case against RCMP officers who arrested an autistic 16-year-old boy in St. Albert. He was injured while in custody, and ASIRT concluded he was unlawfully detained.

Last year, no charges were laid against an Edmonton police officer who kicked an Indigenous teenager in the head, leaving him with life-altering injuries.

Tom Engel, also representing the Nguyen family, said there should be policy changes to ensure these decisions are publicly explained.

"The broader issue is the integrity of the criminal justice system when it comes to decisions made whether to prosecute police officers," he said.

"Because they're not transparent, they're opaque, I think the public is left with the inescapable conclusion that there's a double standard."