A Civil War-Era Strategy That Could Help the Biden Campaign

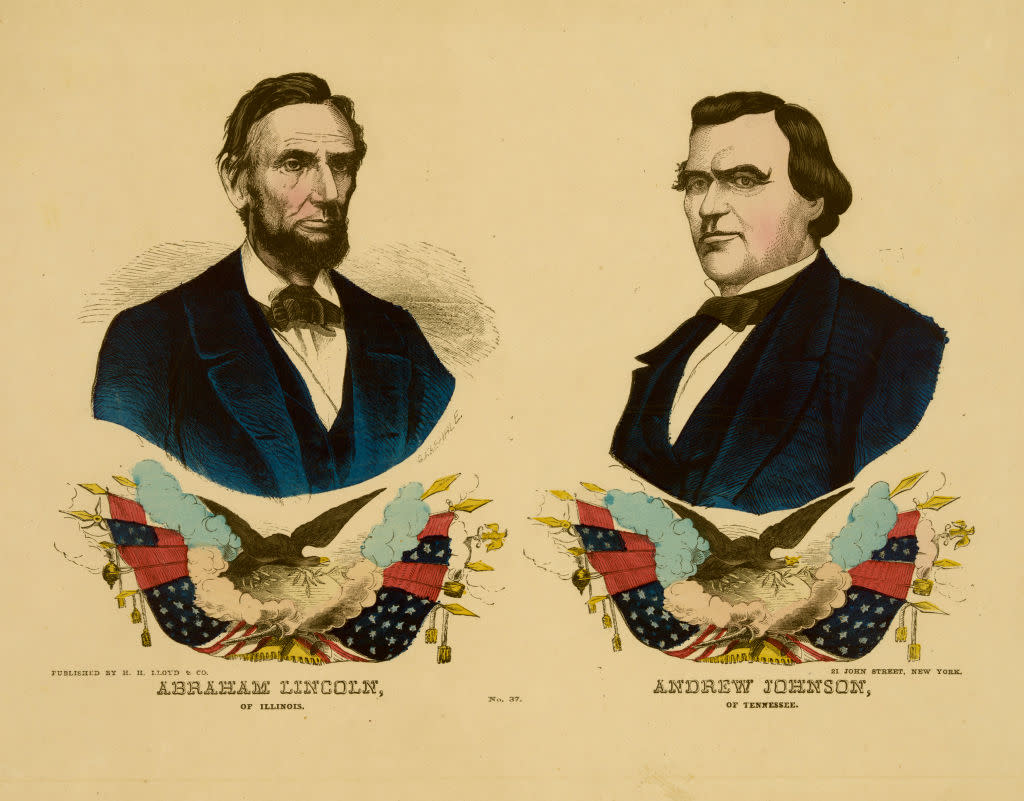

Portrait of Abraham Lincoln (1809 - 1865) and his vice-presidential running mate Andrew Johnson (1808 - 1875) of Tennessee, published by H.H. Lloyd & Company, NY, ca.1864. Credit - Getty Images

According to some polls, Joe Biden and the Democrats may be heading towards a grim outcome in November. Not only does the Senate map favor Republicans, the President’s approval ratings are dismal. There’s some indication the Biden team knows it, too. In an effort to change course, they’ve coined and sold “Bidenonomics” with little success, hit reset on the Biden campaign, and are reportedly in the process of unleashing “Darth Brandon” by letting the President go on the attack. The hope is that a more aggressive Biden like the one Americans saw during the State of the Union address may counteract concerns about his age.

Given the stakes of the election, recent polling, and the apparent desperation of the Biden camp, here’s a novel idea: How about resetting their coalition by appealing to disaffected Republicans in the name of national unity? As a token of their seriousness, they should even think about changing their name.

Read more: Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

As out-of-left-field as it sounds, it wouldn’t be the first time a major party changed its name in advance of a make-or-break election. Indeed, it was this move that just might have saved President Abraham Lincoln’s re-election and the nation from collapse.

In the election of 1864, with the Civil War still far from over, Lincoln’s re-election was in doubt. As that long year began, he wasn’t sure he would win his party’s nomination, much less the Presidency.

In the spring of 1864, several more radical Republicans moved to replace him with Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase. The argument was that Lincoln had moved too slowly on emancipation and had been too conciliatory toward the South when it came to using the full breadth of federal power. Chase, the leader of the radicals, had also been angling for the Presidency from the very start of the war.

Read More: ‘Never Means Never’: A ‘Never Trump’ Republican on Where the Movement Goes Next

Lincoln survived this intra-party campaign, but it was never clear the radical wing of his party would support him. Some anti-Lincoln Republicans would even resuscitate the putsch later that summer by supporting John C. Fremont, the 1856 Republican Presidential candidate, under the banner of their own break-away party, the Radical Democratic Party.

The Democrats were just as fiercely divided about the direction of the party and the nation: Some “War Democrats” supported the continuation of the war; other “Peace Democrats,” also known as “Copperheads,” after the snake, demanded peace with the South, even if it meant breaking up the Union or undoing emancipation.

To add to the Democratic confusion, the party chose former General George McClellan as their standard-bearer. McClellan wasn’t a politician by trade. He was the one-time head of the U.S. army in the east, who had repeatedly clashed with Lincoln earlier in the war. The President finally sacked him after he failed to pursue Robert E. Lee’s army following the battle of Antietam in November of 1862.

The problem with McClellan, as a candidate, was that he tried to chart a middle way between the two factions within the Democratic party. He supported continuing the war and restoring the Union, but he also spoke out against emancipation. Such positions were not just evasive. They also conflicted with the Democratic Party platform — which had been written by Clement Valandignham of Ohio, a notorious “Copperhead,” and which called for settling with the South. As a result, many Democrats who supported the war feared that McClellan just might be a Trojan horse for the “Peace” faction.

So, in a bid to capture disaffected “War Democrats,” national Republican leaders did away with their name.

They called their national convention, which met in Baltimore of that year, the “National Union” convention and rebranded themselves as a “National Union Party.” The name change arose partly from a shared loyalty not to party but to the sanctity of the U.S. government; yet it also arose from the fact that Unionist delegates from border states or occupied states like Arkansas and Tennessee were in attendance and had been invited to give speeches. Many of these delegates had never been Republicans and felt they could never support a Republican or “Abolition” Party but could justify support of a new Lincoln-led party dedicated to the idea of “Union.”

That fall, Lincoln ran not as a Republican, but as the head of the “National Union Party.” The gesture was mostly symbolic, but it reflected a strategic attempt to forge a new electoral coalition by appealing to national unity. For all intents and purposes, the party remained dominated by Republicans but the name change gave war-supporting Democrats and Southern Unionists the political cover needed to join them.

Read More: Lincoln Saved American Democracy. We Can Too

To better make their case, the new party even chose Andrew Johnson, a Southern Unionist from Tennessee and a one-time Democrat, as Lincoln’s new running mate.

After the war’s end and Lincoln’s assassination, Republicans would come to rue choosing Johnson as he worked to undermine the GOP’s Reconstruction efforts.

But, as an electoral move it worked. By adopting the “National Union” label, the party essentially took old affiliations off the ballot and made the election a referendum on the sanctity of the American Union.

Lincoln and other national Republicans won big. The President tallied 221 electoral college votes to McClellan’s 21 and won the popular vote by a margin of roughly 10 percent. While many state parties retained the Republican name, they did just as well. Republicans maintained a majority in the Senate and increased their majority in the House. In turn, the war continued, the Confederacy surrendered, and slavery died — and all in a matter of months. The union prevailed, but had Lincoln lost or not received the mandate that he did it is unclear how the final months of the war would have gone.

Such a landslide result is probably out of reach for Biden and the Democrats. American politics have become deeply polarized and entrenched, producing national elections which hang on razor-thin margins. Yet one lesson to come out of the Republican primary is that anti-Trump, or "Never-Trump,” voters in the GOP still exist. Nikki Haley may have lost, even decisively so, but polling shows that there is a Trump sized gap in the party where old Reaganesque Republicans used to be. Despite attempts to whitewash the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection, attacking American democracy has proved too much for some Republicans, including Trump’s former Vice President, Mike Pence.

Disaffected Republicans, in other words, are out there if the Democrats could reach them. This raises the question: is it time to revive the National Union Party?

Like Lincoln and the Republicans in 1864, the fate of America may depend on it.

Bennett Parten is an assistant professor of history at Georgia Southern University. His writing has appeared in The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Conversation, Civil War Monitor, Zocalo Public Square, and The Washington Post, among others.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

Write to Made by History at madebyhistory@time.com.