What Churchill Really Thought of His Enemies

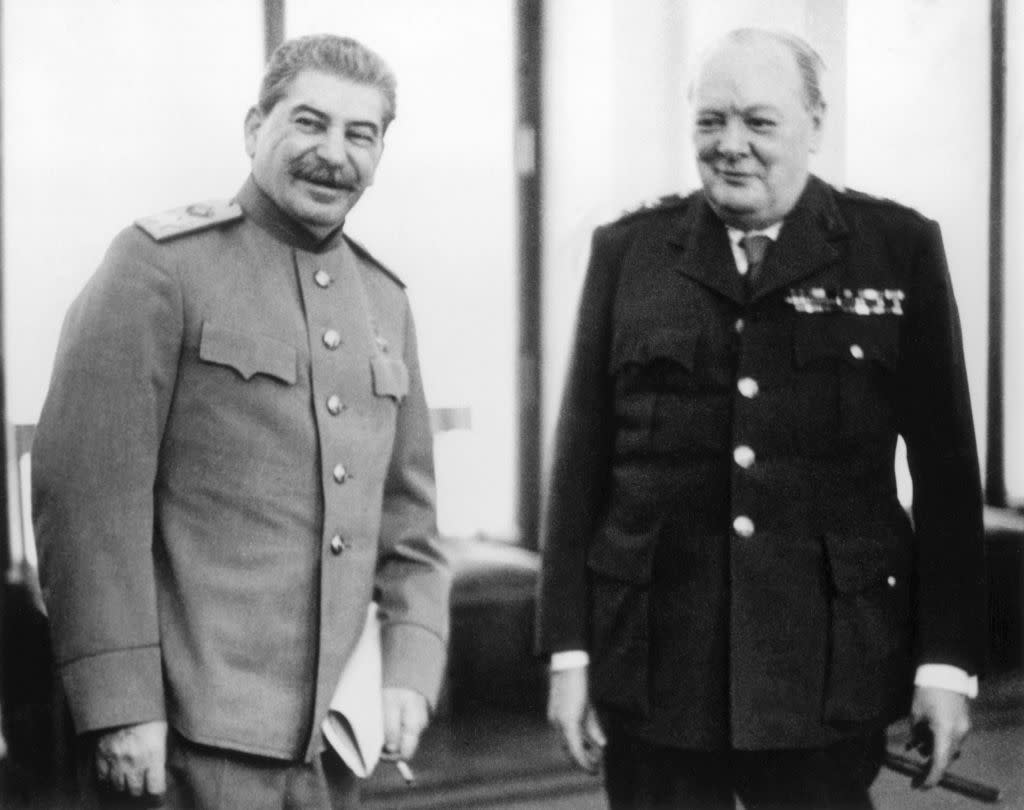

Marshal Joseph Stalin (1879 - 1953) and Winston Churchill (1874 - 1965) together at the Livedia Palace in Yalta, where they were both present for the conference in 1945. Credit - Central Press-Getty Images

In 2024 Winston Churchill is 150 years young. A product of Victorian Britain, born in 1874, he has proved a hardy perennial—lauded by many for his defiance of Nazism, castigated by others for his colonial worldview. Churchill was sure that men made history. (And, yes, he meant men—not women.) Relishing the cut and thrust of international politics, he loved to measure himself against other world leaders—foes as well as friends. Yet his judgment of their personalities was often coloured by his vivid historical image of their countries.

Take, for instance, the two fascist dictators: Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler. Churchill regarded the Italian Duce as a great man who eventually lost his way by taking on Great Britain. In his prime, Mussolini looked the part: strong jaw, bodybuilder torso, mesmeric eyes, and (when needed) a radiant smile. Churchill always praised him for stopping the Bolshevist tide spreading across Western Europe after 1918. And, one senses, behind the Duce Winston saw the greatness of imperial Rome, which had gripped him since youthful immersion in Edward Gibbon’s monumental history and the epic poems of Thomas Babington Macaulay. Even in 1940, Churchill still considered Mussolini “a great man” but judged his decision to side with “Attila” and the “barbarous Huns” to be his fatal mistake—by failing to understand “the strength of Britain” and Its imperial greatness.

By contrast, the civilian Hitler—with his toothbrush moustache and travelling salesman garb— never impressed, and his rants as Führer after 1933 seemed sinister, even comical. What worried Churchill in the 1930s was not the man but his country’s military machine which, he could not forget, had crushed France in 1870 and bled Britain white in 1914-18. Germany’s air rearmament in the 1930s meant that the Luftwaffe might soon be able to leap over the Channel, what Shakespeare had called England’s “moat defensive.”

Churchill’s lack of interest in Hitler as a leader is ironic because the Führer’s breath-taking gamble in May 1940—risking most of his tank divisions in a thrust around the flank of the French and British armies in Belgium—knocked France out of the war in a few weeks, leaving Germany dominant across continental Europe. Hitler’s greatest victory made possible Churchill’s finest hour. Losing his main ally just as he became Prime Minister forced Winston to improvise. Rarely appreciated now because of his “bulldog” stereotype, this improvisation was a salient feature of his own greatness.

The fall of France impelled Churchill’s frenetic efforts to woo new and challenging allies: above all Franklin Roosevelt and Josef Stalin. The Soviet leader was the most unlikely bedfellow. After the Bolshevik Revolution, Winston had wanted to “strangle Bolshevism in its cradle.” He never relaxed his antipathy toward communism but, when the German army invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, he made clear that any foe of Hitler (now singled out as “a monster of wickedness”) should be treated as Britain’s friend.

What helped Churchill square the circle was his personal admiration for Stalin, whom he got to know personally from August 1942: a mass murderer like Hitler but very different in style. Rarely ranting, with a nice line in dry humour, this was a man with whom, despite the impediments of translation, it seemed possible to do business. In fact, Churchill came to see Stalin as a kind of moderate, keeping at bay dark forces in the bowels of the Kremlin—perhaps the Politburo, maybe the Marshals.

Incredible as it may seem now, the leader who delivered the “Iron Curtain” speech in March 1946 told his Cabinet a year before, after returning from the Yalta conference: “Poor Neville Chamberlain believed he could trust Hitler. He was wrong. But I don’t think I’m wrong about Stalin.” This was a faith that Churchill hung onto, with a few blips, for the rest of his political life. Indeed he sought to justify his second term in 1951-5 (now nearing 80) because of the existential need, in the nuclear age, for another “parley at the summit” with Stalin, for which he claimed unique credentials on account of his wartime experience.

Churchill waged war not merely to protect Great Britain but also to preserve the British Empire. And he viewed Mohandas K. Gandhi as a mortal threat to the jewel in the imperial crown: India, where Churchill had served as a young subaltern in the late 1890s. Whereas he justified the Empire as a way to civilize barbarians, Gandhi had apparently gone in the opposite direction. Trained as a lawyer at London’s Inns of Court but now dressed as a “half-naked fakir” he seemed a con man, truly a faker. Worse still, his creed of non-violent resistance challenged everything Churchill believed about power and masculinity. The little Indian in his loin cloth mobilized the power of powerlessness in ways that defied the Great Briton and undermined the empire he loved.

Churchill’s classic “frenemy” was General Charles de Gaulle, who fled to Britain after the fall of France and was entirely dependent on Churchillian hospitality. The Prime Minister welcomed de Gaulle’s Free French forces as a sign that Britain was not entirely alone in 1940 but had no intention of treating him as the future leader of postwar France. De Gaulle, however, insisted that France was still a great power and that he was its current embodiment: “la France libre, c’est moi.” The rows between the two men were often incandescent but, if the roles had been reversed, Churchill would surely have been just as much of a pain to Le Grand Charles. After the war Winston admitted (privately), “I should be sorry to live in a country governed by de Gaulle, but I should be sorry to live in a world, or with a France, in which there was not a de Gaulle.”

Winston Churchill longed to win the accolade of “greatness.” And these jousts with his great contemporaries help us better understand what that word meant for him. If we’re ready to move beyond the encrusted stereotypes, Churchill @ 150 becomes more human—and more interesting.

Contact us at letters@time.com.