Christos Tsiolkas's new novel celebrates a quiet ethics of care in a culturally noisy world

Christos Tsiolkas’s eighth novel, The In-Between, is a work of social realism set in the immediate present – a return to the form and style of some of his most popular novels.

This follows his experiment with cinematic techniques and authorial presence in 7 ½ (2021), and the significant historical shift of Damascus (2019), which was based around the gospels and letters of St Paul, and focused on characters one or two generations from the death of Christ.

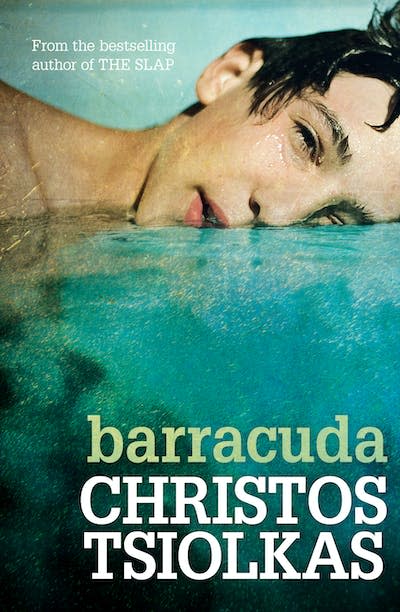

But The In-Between’s scope is smaller, more intimate than Tsiolkas’s earlier social-realist works, like The Slap (2010) and Barracuda (2015), which were concerned with big themes about national and global identities.

Tsiolkas described both of those as “social problem” or “condition of Australia” novels. By contrast, The In-Between is more interested in the individual experience, individual relationships, and our individual influences on one another.

Perhaps for this reason, The In-Between is structured as a series of vignettes, or crucial scenes in the lives of its protagonists – a kind of spotlighting of moments, each set on an intimate stage.

Review: The In-Between – Christos Tsiolkas (Allen & Unwin)

The primary focus throughout is on Perry and Ivan, men in their mid-fifties who embark upon a new relationship, each harbouring and attempting to overcome the hurts and resentments of the past.

But these dominant scenes are intercut – via Tsiolkas’s enduring interest in cinematic style – by glimpses into the lives of other characters, seen and understood only for a moment before they are gone from the narrative.

The effect is to show webs of interconnection between everyone in our ordinary lives, attending to the ways we cross paths, and the impacts of one person on another, whether big or small.

Read more: Christos Tsiolkas, the 'blasphemous' artist and Barracuda

Betrayal, hurt and the news media

Ultimately, these interactions or encounters emphasise the importance of kindness and tolerance. We each occupy our own world, which is naturally all-important and all-encompassing to its protagonist: the self. But those worlds do bump into one another. We must try our best, the novel suggests, to make those bumps gentle, or bear the repercussions.

These consequences of our own weaknesses, and those of others, resonate years after the fact, for both perpetrator and victim. Ivan recalls how his 19-year-old daughter had determined to retain her strength and composure after a sexual assault. Ivan himself must endure self-loathing at his own uncontrolled violence, towards a lover who betrayed him.

Both Perry and the wife of his married former lover, Gerard, must live with the memory of Gerard’s cruel and selfish taunts, which intrude on the present.

And a middle-aged man must suffer the guilty knowledge his brattish tantrum likely caused the heart attack that killed his doting mother. The simple lament, “But I love you”, is repeated, as if to emphasise the horror of realising the hurt a trusted other can inflict.

An evolution of this interest in betrayal and hurt lies in the novel’s meditations on the value of the news media, especially post-COVID. Ivan, in particular, detests the news, because “none of it was trustworthy […] every network and media service was compromised by venality and ideology”.

If you can’t trust a source that frames itself as objective to refrain from petty hurt and injustice, then why engage with it, he insists: “It doesn’t make me happy.” But Evelyn, a friend of a friend, argues with him: “I read to know where injustices are occurring in my world.” But there is a flaw in her logic, Perry observes:

And what knowledge of the world does The New York Times give you? […] I’m not going to hear anything about Australia in The New York Times, am I?

His point is that large global news corporations may report on major national or international events, but they don’t tell us the news that is, arguably, most important: what’s happening in those webs of interconnection closest to us. His argument implies: how big can a community of care and of knowledge truly be?

Class and the cultural cringe

Such an interest in the world at large appears to be an extension of the Australian “cultural cringe”, now manifested as an insistence by some characters on Australia’s racism and conservatism.

For them, Australia is written off – “a racist shithole”. These are characters “in-between” class, “middle-class Australians” with a “tendency […] to endlessly deride their own country”, demonstrating a “habit” shared by “the bourgeoisie the world over”, as Perry observes. “Cosmopolitan Europeans are just as annoying in their shallow, condescending generalisations,” he continues.

Such generalisations pepper the narrative, and are even shared by Perry himself, who thinks, for instance, “Touts les australiens sont comme des enfants”. (All Australians are like children.) Meanwhile, a Greek taxi driver criticises Australians’ insularity and their reluctance to learn even a few words of his language. A guest in a restaurant (misidentifying the men’s nationality) mocks Ivan for making a loud expression of approval: “It’s morning and the Englishman is already drunk.”

These kinds of derision represent criticism without an ethic of care, or tolerance for the other. Instead, Tsiolkas celebrates – as he does in all of his work – those who create, tend, or share. Especially when this is constituted by manual labour: the work of the hands.

Stu, Ivan’s workmate, a gardener and landscaper, possesses an “odour” that “is harsh, defiant, that compound of sweat and tobacco and earth, the masculine scents simultaneously sour and stirring”. For Tsiolkas, this is always the mark of authenticity and honesty.

Anna, an elderly client of Ivan’s, is similarly valued: appreciated for her uncritical generosity and hospitality, for the coffee and cakes she serves, for her devotion to her family and her extension of this to all in her immediate community.

Anna’s difficult decision to renovate the “fertile wonder” of her garden, replacing it with landscaping that will be easier for her to tend, is an example of the broader way her ethic of care seems to be dwindling in the contemporary world.

Another young couple for whom Ivan works represent selfishness at worst, individualism at best. The young woman never invites the landscapers inside (as Anna had done), never offers them a drink or use of the bathroom. Similarly, Ivan is forced out of his own carefully renovated home after his former lover demands his financial share in the property after their split.

But Ivan’s daughter’s decision to purchase a small house in a once-industrial suburb suggests the counter to this loss. Kat will invest in the home, and by extension, in the suburb – as will other young families like her own. The gardens and houses will be tended. The suburb and its community will be revived.

Choosing imperfect love

Like Tsiolkas’s most recent novel, 7 ½, The In-Between insists on the simple power of choosing love: of accepting flaws, mistakes, imperfections, and choosing love anyway.

This morality was gestured towards at the end of The Slap, and perhaps too in The Jesus Man and Barracuda, all of which emphasise some kind of friendship, community or connection as antidotes to the weaknesses of fear and hostility.

The happiness Perry and Ivan seek throughout the novel can ultimately, it seems, only be found when we truly accept the other as they are and accept the past as it occurred – instead of living with bitterness, petty aggression, old hurts and quarrels, or masking and lying out of malice.

Yet, at the same time, the novel presents a sense of the arbitrariness and pointlessness of such connections. Anna’s abrupt death is one such instance - her “joyous laughter”, so “solid”, such a “guide” for Ivan, is snuffed out in a moment.

Another comes in the final paragraphs of the novel, as an apparently loving couple move into and then out of the narrative’s spotlight:

They are there, a faint silhouette in the black of the night, impossible to tell where one ends and the other begins. There is that faint impression. Then there is the merging, the disappearing, and the belonging to the night.

There is an echo of Virginia Woolf’s concept of “moments of being” here. In a sense, the reader is encouraged to recognise those intimate webs of interconnection – even as they also bear witness to life’s inevitable chaos.

Life is fleeting, love is fleeting, the scene suggests. But it still matters, even if life is simply a series of moments “in-between”.

This article is republished from The Conversation is the world's leading publisher of research-based news and analysis. A unique collaboration between academics and journalists. It was written by: Jessica Gildersleeve, University of Southern Queensland.

Read more:

Jessica Gildersleeve does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.