'My brother will pick it up, what's your PayID?' How to avoid this scam when selling stuff online

You’ve done it. You’ve finally bought that new sofa you wanted so much. The old one is still perfectly good to sit on, so you jump online to try and get a little bit of cash for it.

Every day, thousands of Australians list their unwanted things on online trading sites such as Facebook Marketplace and Gumtree. It’s a fast and convenient option, not to mention it helps us to divert goods from landfill.

Unfortunately, scammers constantly target unsuspecting buyers and sellers. More than A$45 million was reported lost through fraudulent buying and selling schemes in 2022.

The popularity of online marketplaces has made them a fertile ground for fraudsters. There have been recent reports of offenders using these platforms to physically attack those selling goods.

However, it is more likely scammers will try to gain money through payment methods. The PayID scam is a popular example of this, with Australians losing more than $260,000 through this specific approach in 2022.

What is PayID?

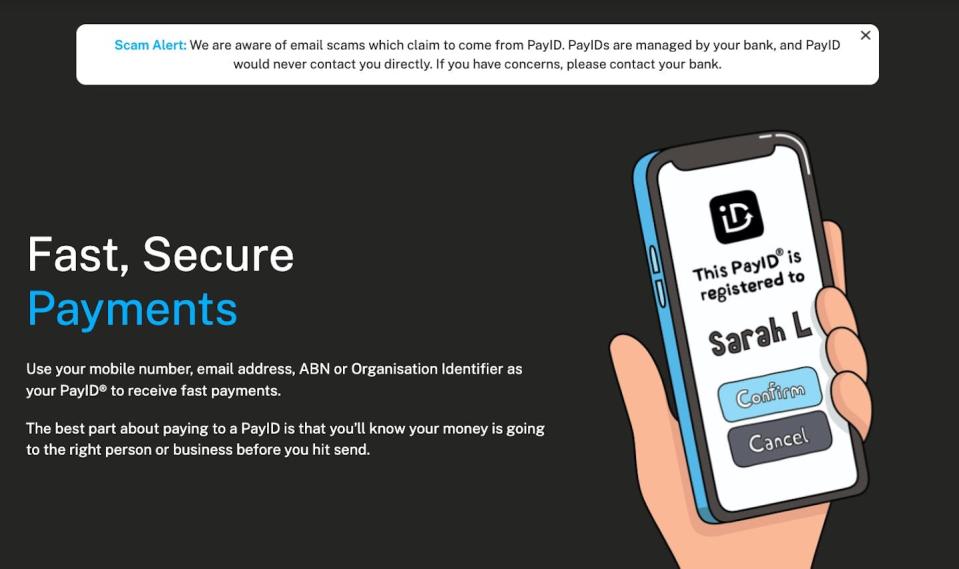

PayID is a legitimate form of electronic payment introduced in Australia in 2018 to overcome incorrect payments as well as reduce fraud – by showing the recipient’s name to the person making the transaction. It aims to simplify the transfer of money. Importantly, PayID reduces the need to remember bank account and BSB numbers, and overcomes the issue when these are entered incorrectly.

To set up a PayID, consumers can use their phone number, email address or ABN as a form of identification. The bank will verify the person owns this information, and then link the person’s bank account to this unique identifier.

To transfer money using PayID, most online banking systems will ask for the PayID of the recipient. By simply typing in the phone number, email address or ABN, it will show the name of the intended recipient. If it is correct, the customer can authorise payment to be made. If the name shown is incorrect, the customer can easily cancel the transaction.

Read more: PayID data breaches show Australia's banks need to be more vigilant to hacking

How does the PayID scam work?

If you’re advertising an item online, a scammer will make contact to purchase the item. They usually will not question the price, and they are unlikely to even want to view the item. In many cases, they will say a family member or friend will collect it from you.

The offender will then urge you to accept payment through PayID. Once you’ve shared your PayID (usually phone number or email address) and the scammer has this information, a few things may happen.

The offender will say they have made the payment, but it cannot be processed because you don’t have a suitable PayID account. You will be told you either need to “upgrade” the account and/or make an additional payment to release the funds.

The offender will then say they have paid the extra amount required and ask you to reimburse the additional funds they have spent. If you do transfer any money, it will go straight to the scammer and be lost.

As part of this, offenders will create text messages and emails that appear to be from PayID, confirming payments or advising of problems. Scarily, such messages may even appear in an existing SMS thread with your bank. You may think they are genuine, but they are fake, designed to deceive you into transferring money to the offender.

Read more: Scammers can slip fake texts into legitimate SMS threads. Will a government crackdown stop them?

How do I avoid a PayID scam?

There are several warning signs to look out for when selling goods online:

PayID is a free service. There are no costs associated with using it, and therefore no fees will ever need to be paid

PayID is administered through individual banks. PayID will never communicate directly with customers through texts, emails, or phone calls. Any correspondence which says it is “from PayID” is fake

a genuine buyer will usually inspect and collect any goods. A buyer who says they will send a family member or friend to collect the item is a red flag, especially if they are unwilling to pay in cash.

What to do if you have been scammed?

If you think you have been a victim of a PayID scam, you should contact your bank or financial institution immediately. The quicker you can do this, the better.

You can report any financial losses to ReportCyber, an online police reporting portal for cyber incidents.

You can also report the incident to Scamwatch to assist with education and awareness activities.

If you have had any of your personal information compromised, you can access support from IDCARE.

In 2023 so far, Australians have reported more than $32 million lost to buying and selling schemes, including the PayID scam. Stay vigilant when buying or selling goods online, and consult the Scamwatch website for details on other types of scams.

Read more: Being bombarded with delivery and post office text scams? Here's why — and what can be done

This article is republished from The Conversation is the world's leading publisher of research-based news and analysis. A unique collaboration between academics and journalists. It was written by: Cassandra Cross, Queensland University of Technology.

Read more:

Cassandra Cross has previously received funding from the Australian Institute of Criminology and the Cybersecurity Cooperative Research Centre.