How a Black pioneer helped the boom of northern B.C.'s gold rush

John Robert Giscome left his mark on British Columbia.

A trail and small community north of Prince George, B.C., are named in his honour.

But Krystal Leason, executive director of the Huble Homestead/Giscome Portage Heritage Society in Prince George, says many people don't know much about the prospector and his role in northern B.C.'s gold rush.

"[People] often assume he's white and so they're very surprised to discover that he was actually a Black man from Jamaica, which is pretty neat and really speaks to the early diversity of B.C. and the contributions of Black people to our province's history," Leason said.

For Cecil Giscombe, a writer and professor of English at the University of California Berkeley, learning about the prospector has given him insight into a distant relative.

"The Giscome/Giscombe name, there aren't very many of us," Giscombe told CBC News. "It's a small family and all of us trace our heritage back to the north coast of Jamaica."

Leason and Giscombe hope more people learn about Giscome's journey affected travel into northern B.C. for years to come.

"Giscome is kind of a minor figure … [but he] opened up the north for all sorts of mercantile things," said Giscombe.

John Robert Giscome and Henry McDame were allegedly the first non-Indigenous people to travel on the trail now known as the Giscome Portage Trail. After Giscome publicized knowledge of the shortcut, it became the main way of travel through Northern B.C. during the gold rush. (Huble Homestead/Giscome Portage Heritage Society)

Retracing 'a hero's journey'

Records show Giscome left his hometown of Saint Mary, Jamaica in 1854 to work on California's Panama Railway.

Giscome and nearly 600 other Black people left California due to discrimination and harassment, according to Giscombe, and settled on Vancouver Island at the invitation of James Douglas, B.C.'s first governor.

"Douglas greeted them happily … he was afraid that British Colombia was about to be annexed by the United States. He was happy to have people who did not like America," Giscombe said.

Giscome decided to seek his fortune in gold. In Quesnel, he met Bahamian Henry McDame, who joined him to prospect the Peace River country.

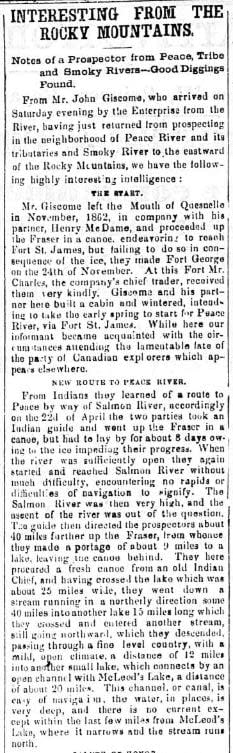

As Giscome shared in an 1863 article in the British Colonist newspaper, the pair and a Lheidli T'enneh guide attempted to travel a well-known, but roundabout, route to Fort St. James.

With ice and high water levels impeding their progress, the unnamed guide suggested a shortcut, which Leason says cut a 100-kilometre trip down to just 12 kilometres.

In 1863, John Robert Giscome relayed information about his travels to and through the Peace River country for an article in the British Colonist. The story he relayed of a shortcut between two waterways led to the formation of the Giscome Portage. (British Colonist archives)

The group was greeted by "a salute of about 30 shots" when they arrived at a Hudson's Bay Company fort for being the first non-Indigenous people to travel that way, the British Colonist article says.

"It really was a game changer in the way people access the north," said Leason, adding the article created awareness of the route and prompted it to be named Giscome Portage.

"In the early 1900s when settlement was really booming in Fort George and this region … there's hundreds of people passing through … for settlement, for mining, for trapping, for prospecting … on Giscome Portage."

Leason says while not much is known about McDame, records show Giscome "actually struck gold" as a prospector.

She adds he left $21,000, the equivalent of about $500,000 in today's dollars, to his Victoria landlady after he died in 1907.

Cecil Giscombe biked and camped from Vancouver to Prince George, B.C., to retrace and better understand the trip taken by his distant relative in the 1800s. (Cecil Giscombe)

In 1991, Giscombe followed Giscome's steps through "a hero's journey," biking and camping all the way to Prince George.

"I camped [near Giscome Portage] trying to feel authentic and being vaguely nervous about the bears," said Giscombe, who released books in 1998 and 2000 about his discoveries.

"But walking the portage, just being there and breathing … and you're just feeling incredibly ebullient like, oh wow, oh sugar, this is beautiful."

Since then, Giscombe has travelled to Victoria and Jamaica to trace more history, but every year he finds himself back in Prince George to visit friends and walk the trail made popular by a distant, but dear, relative.

For more stories about the experiences of Black Canadians — from anti-Black racism to success stories within the Black community — check out Being Black in Canada, a CBC project Black Canadians can be proud of. You can read more stories here.

(CBC)