A Bellwether Pennsylvania Factory Town Is Wary of Bidenomics

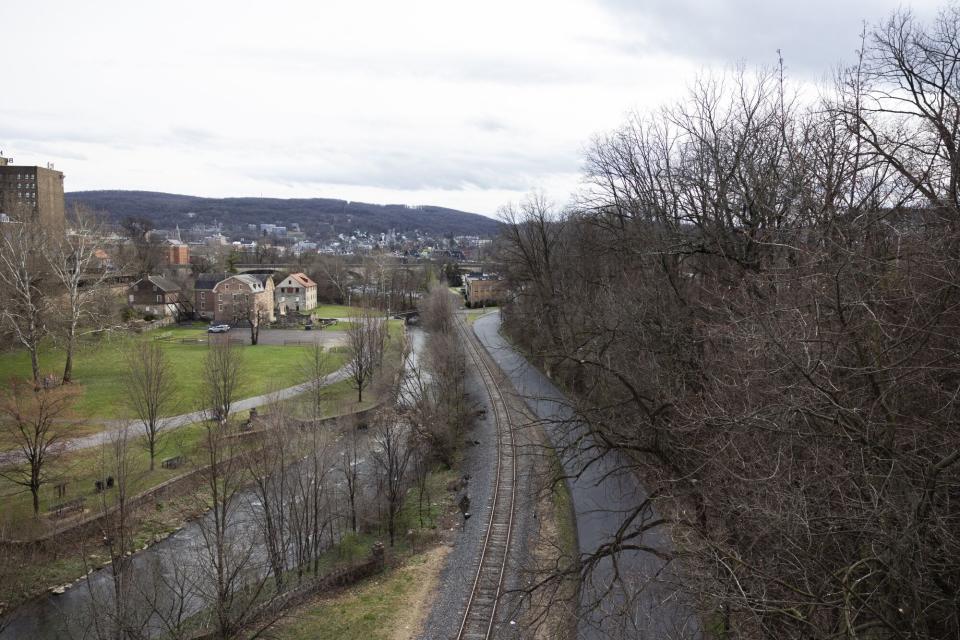

(Bloomberg) -- Bethlehem Steel was once a symbol of American manufacturing might, the output of its blast furnaces used in the construction of the Empire State Building and the Golden Gate Bridge. Based in Northampton County, Pennsylvania, it was the world’s second-largest steelmaker at its peak, employing thousands across the region until production ended in the late 1990s.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Baltimore Wants to Sell Hundreds of Vacant Homes for $1 Each

Sam Bankman-Fried Says 50-Year Sentence Only Suitable for a ‘Super Villain’

Justice Department to Sue Apple for Antitrust Violations as Soon as Thursday

Switzerland Surprises With Rate Cut, Moving Ahead of ECB and Fed

China on Track to Be Ready to Invade Taiwan by 2027, US Says

Two decades on, reviving US industry is a core focus of the presidential election — and Northampton is a bellwether county in a swing state that will help decide the outcome.

President Joe Biden is basing his campaign for re-election on his landmark push to rebuild US manufacturing with a focus on creating future-oriented jobs in clean energy and high-tech industries. His goal is to showcase his record and translate that into votes in places like Northampton County and the wider Lehigh Valley that was long famous for its heavy industry.

Interviews with residents suggest the president has work to do.

Business leaders and elected officials in Northampton County praise the stimulus from Biden’s industrial measures as offering a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity of regeneration. Many voters, however, are preoccupied with the cost of living, and have yet to be convinced that Bidenomics, as the president’s economic policy is known, is yielding much for them.

People like Ken Hank, who builds fire protection valves and says he hasn’t seen any evidence of a boost to manufacturing firms in the county from government policy. “I don’t think they’re getting invested in. I think there could be more help, maybe federal help,” said the 62-year-old. “They’re concentrated on other things like Ukraine and Russia.”

That kind of skepticism will concern the Biden campaign, not just because Hank is a union worker and a Democrat. But because he lives in Northampton, one of just 25 counties in the US — out of more than 3,000 — that have voted for the winner of the presidential race every cycle since 2008.

The Lehigh Valley was synonymous with manufacturing from the early 19th century, its abundant coalfields and iron ore deposits firing the industry that fueled America’s rise. The region’s physical and political landscape has been shaped by the emergence and decline of those mines, waterways and factories, notably Bethlehem Steel.

Remnants of the works are still visible in its namesake city of Bethlehem, where an arts district was built around the plant’s gigantic retired furnaces and an industrial museum sits on the former property. Today, Northampton County touts the quality of its air alongside a tradition of “manufacturing excellence.” It’s exactly the kind of place that Biden needs to reach: He squeezed out Donald Trump by less than 1 percentage point in the county in 2020, a slender lead that could be at risk if supporters question his signature policies.

“How many small towns you know in Pennsylvania and all across the Midwest where there was a factory that for 30, 40 years people were able to work and have a good, decent salary?” the president said at an October event in Philadelphia. “We’re bringing them back, and we’re bringing them back big time.”

As the state where he was born and spent his early childhood, winning is more than just a political imperative for Biden; it’s personal. Having famously grown up in Scranton, about 75 miles to the north of Bethlehem, Biden has made more official visits to Pennsylvania during his presidency to date than any other state except for regular stays at his residence in Delaware. Biden kicked off a tour of battleground states in Pennsylvania on March 8.

Just how much the state means to him — and the political importance he attaches to manufacturing — was illustrated by his unusual intervention in the proposed takeover by Japan’s Nippon Steel Corp. of United States Steel Corp., based in Pennsylvania. It’s “vital” that US Steel “remain an American steel company that is domestically owned and operated,” he said in a March 14 statement.

That intervention paid off. A week later, the United Steelworkers union endorsed Biden for a second term, months after other prominent labor unions made the move to jointly give him their backing.

Yet an additional challenge for the president is to convince those voters who acknowledge the government’s actions to credit him with the improvements they’re witnessing: Both he and Trump are preaching the gospel of an American manufacturing renaissance, with jobs brought back from overseas and China’s access stymied to key technologies including advanced semiconductors.

“A vote for Trump is a vote to keep those manufacturing jobs in America, and add a lot of jobs,” the former president said last month in Michigan, another state steeped in the glories of the US industrial past.

Don Cunningham’s father and great-grandfather both worked at Bethlehem Steel. He witnessed its decline and then ran for city council arguing that the town needed to evolve and diversify economically, later winning office as Bethlehem’s youngest mayor. Now chief executive officer of Lehigh Valley Economic Development, he says the area has recovered by relying on a variety of employers with smaller workforces.

It’s a path he sees continuing irrespective of who is elected.

“Without a doubt the federal government getting engaged in kind of New Deal-esque funding has certainly been helpful,” he said. “We realize that’s probably not going to happen forever. This is like a blip in time.”

With his economic agenda, Biden has sought to address the driving factors behind America’s industrial decline, caused in large part by competition ceded to Southeast Asia in the 1980s and 2000s, as companies left for cheaper labor or automated technology.

That shift particularly devastated a string of states in the Northeast and Midwest, often referred to as the Rust Belt, including Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin. Those states make up Democrats’ “Blue wall,” must-win swing states considered crucial to securing a path to victory in the presidential election. Trump won all three in 2016 with his “America First” agenda.

Biden won them back in 2020, edging out his rival by just 1.2% in Pennsylvania. Trump currently leads Biden 49% to 43% in a head-to-head matchup in the state, according to a Bloomberg News/Morning Consult poll conducted in February.

Despite that, as the White House seeks to engineer a modern manufacturing boom, federal investments have been more substantial elsewhere in the country. Pennsylvania has received tax breaks and funding worth $4 billion from Biden’s agenda. Wisconsin has secured even less at $2 billion, while Michigan holds a substantial $22 billion, according to White House data.

That pales in comparison to states like Texas and Arizona, which have total investments of $123 billion and $80 billion respectively. Both have attracted big-ticket announcements for semiconductor factories, as a result of subsidies available through the Chips and Science Act, bringing a promise of thousands of new jobs with it.

“There’s a huge opportunity for America to shift back,” says historian Mike Piersa, who works at the National Museum of Industrial History in Northampton County. “We’re seeing that it’s not distributed as equally geographically as I think a lot of people would like to see it.”

Manufacturing still accounted for the largest share of the area’s economy in 2022, producing $8.4 billion in gross domestic product.

According to US Bureau of Labor Statistics data, more people are working in manufacturing in the Lehigh Valley under Biden than at any time since 2005. In January, 41,200 people held jobs in the sector. Under Trump, that figure at its height reached about 40,000, before the global pandemic led to layoffs.

Rosier employment prospects have registered with Elaine Olmeda, a retired medical assistant living in Bethlehem. “When I go shopping in the malls, I always see jobs: hiring, hiring, hiring,” said Olmeda, 69, who considers herself a conservative.

But she’s more occupied by the fact that everything has become expensive: “When I go to the grocery markets, I scream.”

Rayni Taylor, a United Steelworkers member and a registered independent, said even though companies are now hiring employees and raising wages, they’re also cutting hours in his industrial park. “We’re making less money now, even with the wage increases,” Taylor said.

The 33-year-old father says he’s struggling to pay for housing costs and groceries on a salary of less than $40,000. He witnessed a nearly 48% increase in his normal expenses in February 2023, just before his first child was born. “I feel like underneath Trump there was some stability in the economy,” he said.

More than half of voters in Pennsylvania, 55%, said Biden’s manufacturing investments have not impacted them or their communities much or at all, according to the Bloomberg News/Morning Consult survey. Only 14% said the investments have impacted them or their community “a lot,” while 32% said it had “some” impact.

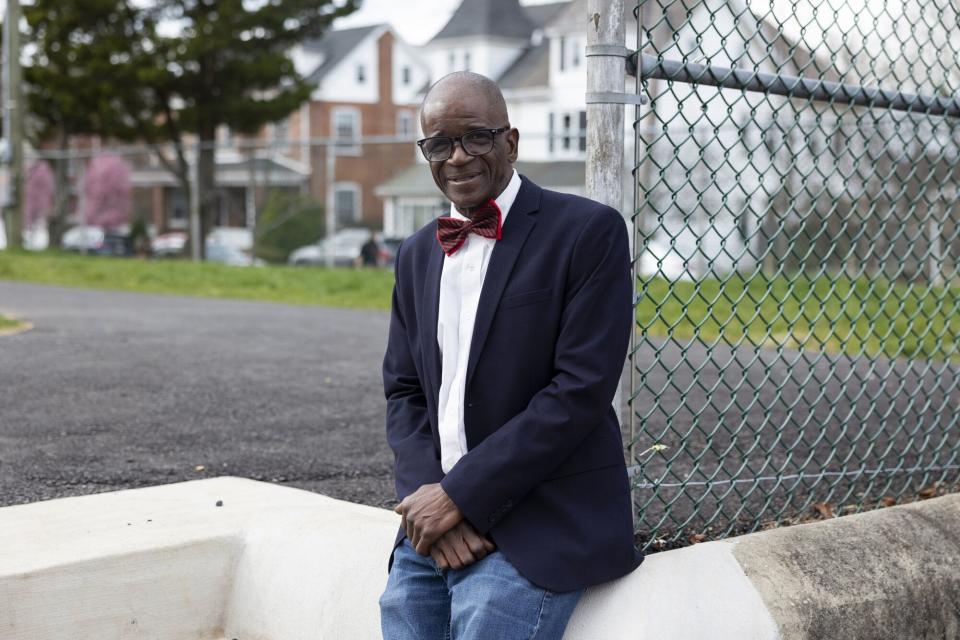

Those kind of sentiments in the state with which he is most closely identified underscore the challenges to Biden’s efforts to revive manufacturing nationwide. Clovis Williams, a long-time Northampton County resident who used to work in construction, says voters aren’t giving the president a chance.

“He’s trying hard to make things better for, especially, the smaller communities,” said Williams, 61. “His policies are working, they are working, and people are just not realizing.”

The president’s “Investing in America” agenda consists of four main policies: the CHIPS Act; a climate-tax-and-healthcare bill called the Inflation Reduction Act; a bipartisan infrastructure law; and the American Rescue Plan, which offered post-pandemic emergency relief. Together they wield more than $1 trillion in funding over ten years. The White House says with private sector commitment, the value will top $3.5 trillion.

Although Pennsylvania hasn’t attracted the kind of headline-grabbing, billion-dollar private sector commitments as other states, different elements of Biden’s economic policies are spurring business activity and upgrades to infrastructure in Northampton County.

Randy Galiotto, the co-owner of Alloy5 Architecture LLC, says the projects his firm handles have increased from about 80 to 180 annually due to demand from public schools and local governments that received funds through the American Rescue Plan, which passed in 2021. The firm’s payroll has increased from a dozen to 25 employees since 2020 to meet the demand.

“It has had a lasting effect,” Galiotto said.

Earlier this year, the Lehigh Valley International Airport was granted more than $40 million from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act to improve freight operations and bolster the region’s logistics industry, including building a new cargo complex. The same bill is offering $9.9 million for one of the city’s busiest streets to add crosswalks and bike lanes.

iDEAL Semiconductor Devices Inc., a Bethlehem-based startup that designs microchips, plans to apply for research and development funding from the CHIPS Act if an opportunity arises. That could help the company accelerate the development of its technology and hire new talent. But even if the firm isn’t awarded money, co-founder Mike Burns says the policy has revived “the entire ecosystem” for semiconductors in the US.

“People need to really think about everything that’s been done. You don’t necessarily feel all of the advantages immediately,” says Democratic Congresswoman Susan Wild, who represents parts of Northampton County and is up for re-election. “The last Congress and this president will be viewed very, very favorably in the long term in terms of what got done.”

Pennsylvania Senator Bob Casey, in an interview, said campaigns have to invest in advertising for voters to understand the full picture of the legislative pieces. “By the time November rolls around I think we will have broken through a lot more,” said the Democrat, who is also running for re-election.

Biden’s political future is likely to depend on it, in Pennsylvania and across the US.

“I can tell you it’s going to be a hard-fought battle for both Trump and Biden,” said Taylor, the union worker. He said that he’s leaning more toward Biden than Trump because of the protections given to workers, but he and “a lot of the common folk” are notably downbeat about the economic outlook.

“We’re seeing a lot of the going ups but we don’t think it’s going to last that long,” Taylor said while walking in the Jacobsburg State Park in Northampton County, an area once famous for a gun factory producing the Henry firearm — the most prominent weapon of the western frontier — and now known for its nature trails. “Right now,” he added, “I guess we’re seeing the calm before the storm.”

--With assistance from Cecile Daurat.

(Updates with USW endorsement in 13th paragraph.)

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

Selling Shohei Ohtani: Can Baseball’s Biggest Talent Transform the Sport?

Wall Street and Silicon Valley Elites Are Warming Up to Trump

OpenAI Sprinting to Keep Up With Startups on AI-Generated Video

Magnificent Seven? It’s More Like the Blazing Two and Tepid Five

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.