9 justices, many opinions: How the Supreme Court tells lawyers, judges and the public about its decisions and disagreements

When the U.S. Supreme Court issues opinions, you may hear that the nine justices reached a 6-3 or a 5-4 decision. You may also hear that certain justices wrote a concurrence or that there were multiple dissents.

Those concurrences and dissents are where Supreme Court justices express disagreement with the majority opinion.

Consider the recent case of Arizona v. Navajo Nation, which examined the Navajo Nation’s water rights in the Colorado River. The court decided 5-4 in favor of Arizona, meaning five justices agreed with the arguments made by the state of Arizona, while four justices agreed with the arguments made by the Navajo Nation.

The opinion issued by the five justices is the decision that serves as precedent for other courts. It is referred to as the “majority opinion” or simply “the opinion.”

The opinion issued by the other four justices is called “the dissenting opinion” or simply “the dissent.” Just as the majority opinion outlines its reasoning and how it reached its conclusion, the dissenting opinion will do the same. Lower courts are required to follow the majority opinion; lower courts are not required to follow the dissenting opinion.

Why issue a dissent if courts are not required to follow it? Dissents have a role and purpose even if they are not the official guide for a court’s decision.

For the record

Justices write dissents for the sake of history, for their personal reputation or as a matter of principle. They want to be on the record for why they believe the majority decision is incorrect.

In the dissent, justices may go step by step through the majority opinion to highlight what they view as errors in the logic, interpretation or holding of the case. The holding is the court’s official answer to the question it is being asked to decide.

You can see an example of this step-by-step approach in the record of the case that overturned federal protection for the right to get an abortion, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health. In that case, the dissent wrote detailed responses to the majority opinion.

Develop the legal argument

A dissent also has a role in helping other justices articulate their arguments.

Before the court issues an opinion, the justices meet in person to discuss their views and their preliminary decisions on the outcome of the case.

Based on that conference, the justices have an idea of what the majority opinion will be and who will agree with it. The chief justice, or else the most senior justice, then assigns one justice to draft the majority opinion. The same process is used in assigning one justice to draft the dissenting opinion.

These draft opinions are then circulated among all the justices, who provide comments and feedback about points they feel are important to incorporate. This review process helps justices decide whether to join an opinion or to write their own if they feel a certain point needs to be addressed.

The value of this process is to hone the arguments in the opinions. The late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg said in a 2009 speech that “there is nothing better than an impressive dissent to lead the author of the majority opinion to refine and clarify her initial circulation.”

Dissents as guidance

Sometimes the reasoning in a dissent is used to adjust future law. It may serve as guidance to lawmakers, or it may form the basis for future cases designed to eventually overturn this initial case.

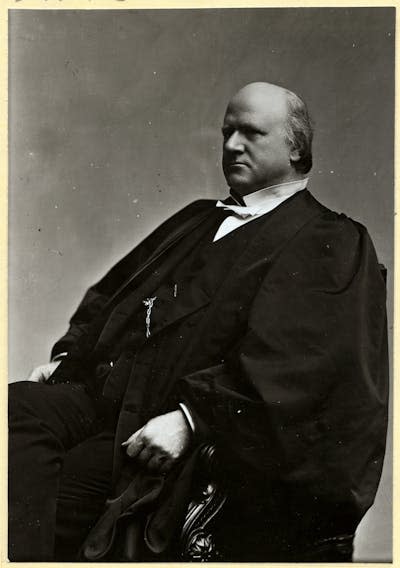

In Plessy v. Ferguson, a case from 1896 challenging a racial segregation law in Louisiana, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation was legal as long as separate but equal facilities and services were available.

There was only one dissent in that case, by Justice John Marshall Harlan. In the dissent, Justice Harlan argued that segregation was unconstitutional: “[t]he arbitrary separation of citizens on the basis of race while they are on a public highway is a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality before the law established by the Constitution. It cannot be justified upon any legal grounds.”

Harlan’s dissent laid the groundwork for the argument ultimately accepted by the court 60 years later, in Brown v. Board of Education, that overturned the Plessy decision and declared racial segregation to be unconstitutional.

Although Harlan is not explicitly mentioned in the Brown decision, the reasoning and arguments he articulated in the Plessy dissent formed the basis for subsequent cases that tested the limits of “separate but equal” and ultimately led the court to overturn that doctrine in Brown.

The dissent is not limited to one opinion. This means that in a 5-4 decision there could theoretically be four separate dissenting opinions.

What about concurrences?

At least five justices must agree with, and sign on to, the majority’s decision. The simplest outcome is when those five justices all agree on a single opinion.

However, a justice in the majority may still disagree with the writing in the majority opinion. For example, a justice may write an additional opinion clarifying the extent of agreement with the majority’s decision. Or a justice may agree with the majority’s decision but not the reasoning and thus choose to write a separate opinion.

These separate opinions by those in agreement with the majority decision are called “concurrences.” They serve similar purposes as dissents by recording a justice’s thinking on an issue, and that thinking could be used in the future on similar cases.

The math can get tricky with concurrences. In the case about water for the Navajo Reservation, four justices signed the majority opinion, while the fifth justice wrote a concurrence. So, four justices in the majority plus one writing a concurrence equals five justices agreeing on a holding.

Additionally, justices in the majority can sign onto the majority opinion as well as a concurring opinion.

In Griswold v. Connecticut, a 1965 case regarding privacy rights, seven justices agreed that a right to privacy could be found in the Constitution, but they disagreed about where that right was based. Five justices signed the majority opinion. Three of those five justices also signed on to a separate concurring opinion. Two other justices did not sign the majority opinion; instead, they each wrote their own separate opinions, concurring with the majority’s conclusion but not joining the majority opinion.

That’s a total of four opinions all agreeing that there is a constitutional right to privacy but disagreeing about where in the Constitution that right can be located.

What should a lower court do with an opinion like in the Griswold case? Lower courts still must follow the majority opinion, but they may choose to incorporate the reasoning from a concurring opinion.

Legal conversations

Concurring and dissenting opinions are a conversation with the majority opinion about the legal issues in the case. So the next time you hear about a concurrence or dissent, pay attention.

At the very least, you can learn about how a particular justice views the issue at hand. What’s more, you may gain a window to where the law is headed in the future.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Ilisabeth S. Bornstein, Bryant University

Read more:

Ilisabeth S. Bornstein does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.