300 million habitable planets in our Milky Way galaxy, say scientists

There are at least 300 million habitable planets in the Milky Way, new NASA research has shown – hinting that it’s less likely that humanity is alone in the universe.

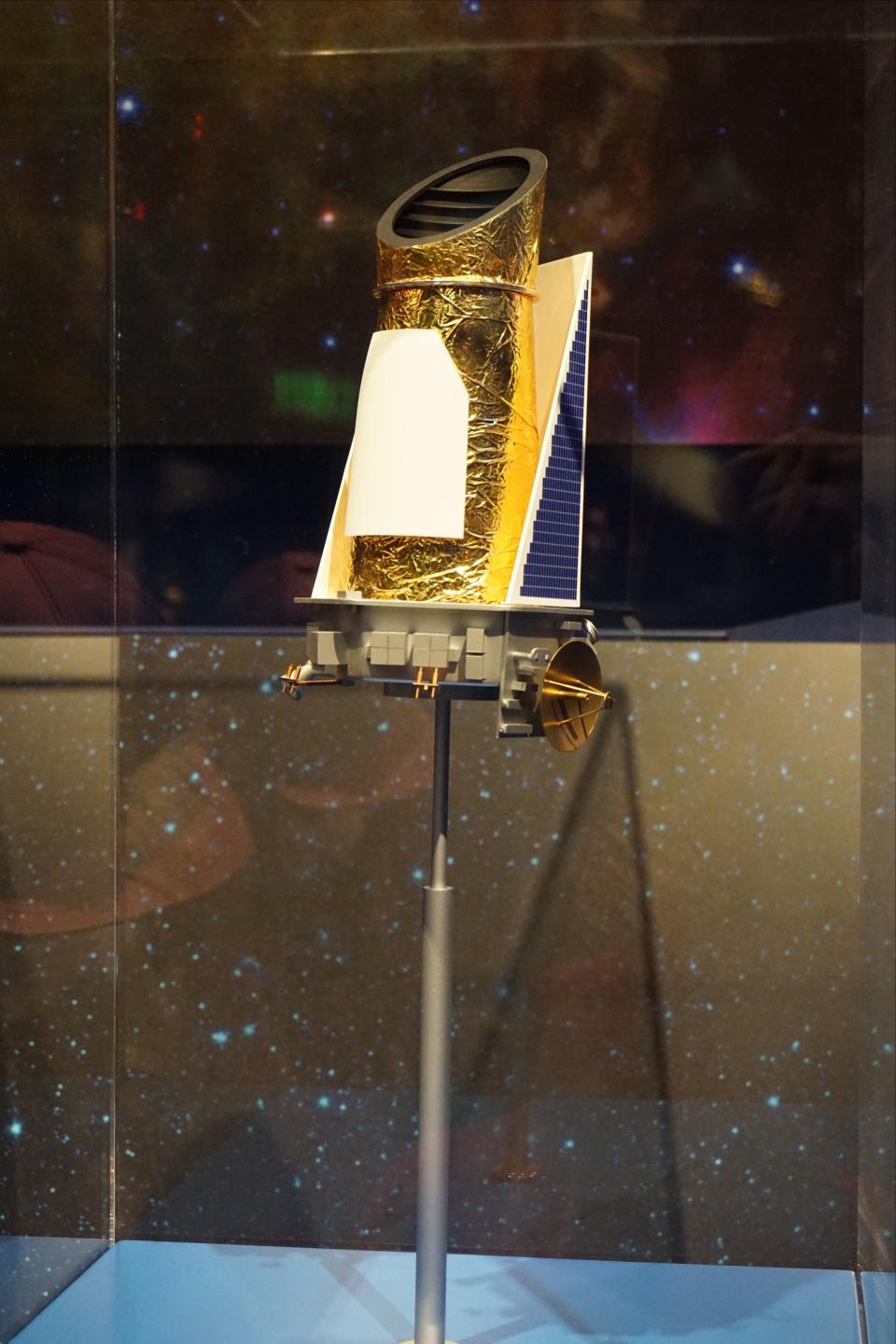

Research based on scans by NASA’s retired planet-hunting Kepler telescope suggest that about half the stars similar in temperature to our sun could have a rocky planet capable of having liquid water on its surface.

That means the planets could potentially harbour life, scientists believe.

Some of these potential planets are also very close to Earth (relatively speaking) with the closest likely to be a mere 20 light years away.

Four are within 30 light years of Earth, the researchers say.

Read more: Mysterious “rogue planet” could be even weirder than we thought

"Kepler already told us there were billions of planets, but now we know a good chunk of those planets might be rocky and habitable," said the lead author Steve Bryson, a researcher at NASA's Ames Research Center in California's Silicon Valley.

"Though this result is far from a final value, and water on a planet's surface is only one of many factors to support life, it's extremely exciting that we calculated these worlds are this common with such high confidence and precision."

The researchers say that there could be many, many more than 300 million habitable planets, according to the research published in the Astronomical Journal.

Read more: Astronomers find closest black hole to Earth

These are the minimum numbers of such planets based on the most conservative estimate that 7% of sun-like stars host such worlds.

However, at the average expected rate of 50%, there could be many more.

For the purposes of calculating this occurrence rate, the team looked at exoplanets between a radius of 0.5 and 1.5 times that of Earth's, narrowing in on planets that are most likely rocky.

This new finding is a significant step forward in Kepler's original mission to understand how many potentially habitable worlds exist in our galaxy.

Previous estimates of the frequency, also known as the occurrence rate, of such planets ignored the relationship between the star's temperature and the kinds of light given off by the star and absorbed by the planet.

The new analysis accounts for these relationships, and provides a more complete understanding of whether or not a given planet might be capable of supporting liquid water, and potentially life.

That approach is made possible by combining Kepler's final dataset of planetary signals with data about each star's energy output from an extensive trove of data from the European Space Agency's Gaia mission.

"We always knew defining habitability simply in terms of a planet's physical distance from a star, so that it's not too hot or cold, left us making a lot of assumptions," said Ravi Kopparapu, an author on the paper and a scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

"Gaia's data on stars allowed us to look at these planets and their stars in an entirely new way."

"Not every star is alike," said Kopparapu. "And neither is every planet."

Watch: NASA’s ‘Robot Hotel’ welcomes first guests on the International Space Station