2023 was the hottest year on record with 'profound consequences' for 1.5°C limit, data shows

2023 was a year of grim climate milestones for the viability of life on Earth.

It saw record-breaking weather including the hottest-ever month and daily global temperature averages briefly surpassing pre-industrial levels by more than 2°C in November.

Now the EU's Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) has confirmed that unprecedented global temperatures from June onwards meant 2023 was the warmest year on record - overtaking 2016 (the previous warmest year) by a large margin.

The record was confirmed in C3S's 2023 Global Climate Highlights report released today (9 January), which underscores how climate change is impacting our planet.

It also explores the main drivers behind 2023’s extremes, including increasing greenhouse gas concentrations and the El Niño weather phenomenon.

2023 confirmed as hottest year on record

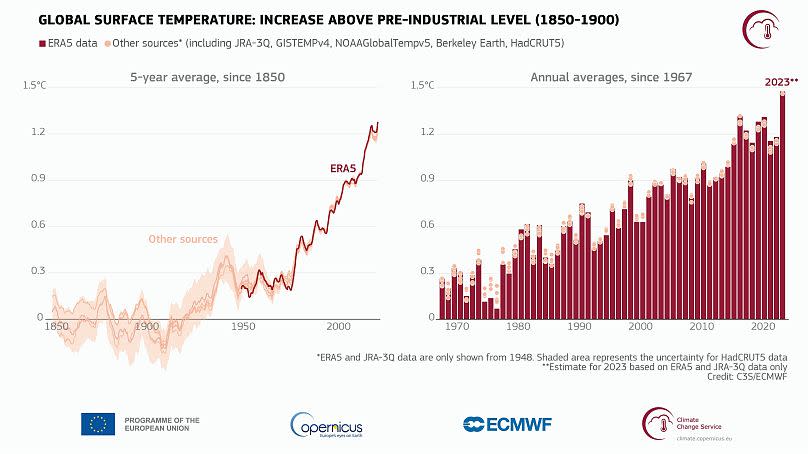

The C3S report confirms 2023 as the warmest year since global temperature data records began in 1850.

“2023 was an exceptional year with climate records tumbling like dominoes,” says Samantha Burgess, Deputy Director of C3S.

Last year saw a global average temperature of 14.98C - 0.17C higher than the previous highest annual value in 2016. 2023 was 0.60C warmer than the 1991-2020 average and 1.48C warmer than the 1850-1900 pre-industrial level.

"Temperatures during 2023 likely exceed those of any period in at least the last 100,000 years," Burgess adds.

It also marks the first time on record that every day within a year has exceeded 1C above the 1850-1900 pre-industrial level, she says.

Climate Now debate: 2023 is set to be the hottest year on record, so why aren’t we taking action?

2023 was the hottest year on record. How are Europe’s cities planning to adapt for even warmer 2024?

Close to 50 per cent of days were more than 1.5C warmer than the 1850-1900 level, and two days in November were more than 2C warmer for the first time ever.

The report also warns it is likely that a 12-month period ending in January or February of this year will exceed 1.5C above the pre-industrial level.

"The Paris Agreement refers to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial level as an average over 20 years. This is different from what we have recorded in 2023 and what might happen in February 2024," says Carlo Buontempo, director of C3S.

"We do expect the limit of the Paris Agreement to be reached sometime in the mid-2030s. As we approach this date, it will gradually become more likely for days, weeks, months and years to be above this level."

"In that sense, the fact that 2023 was so close to 1.5 is a stark reminder of the proximity of the Paris Agreement’s threshold," he adds.

In terms of monthly temperatures, each month from June to December in 2023 was warmer than in any previous year.

December 2023 was the warmest December on record globally, with an average temperature of 13.51C, 0.85C above the 1991-2020 average and 1.78C above the 1850-1900 level for the month.

In Europe, it was the second warmest year on record with temperatures above average for 11 months during 2023. September was the warmest the continent has seen since records began.

2023 ocean temperatures were unusually high

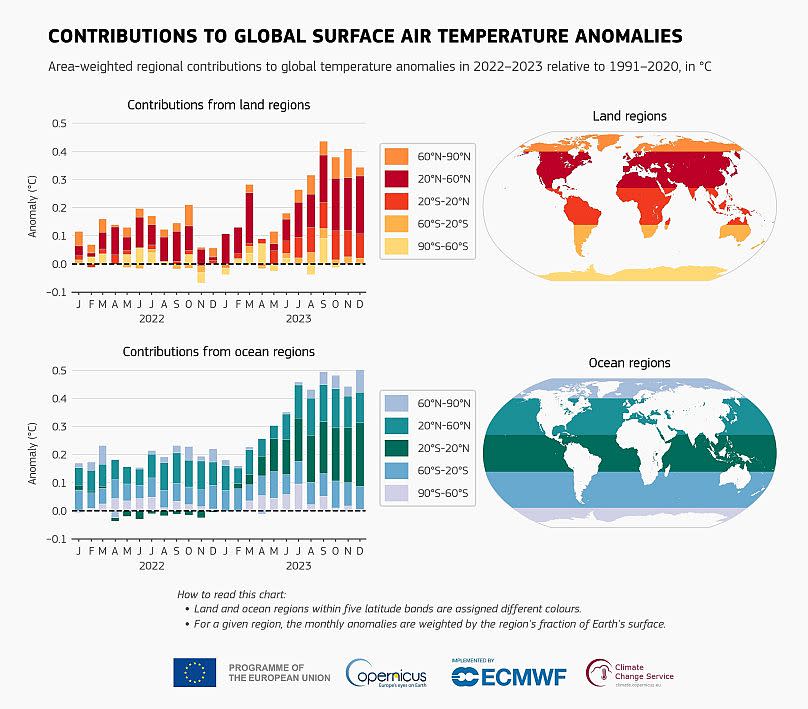

A critical driver of the unusual air temperatures experienced throughout 2023 was unprecedentedly high surface temperatures in the world's oceans. Sea temperature rise is known to be impacted by greenhouse gas emissions.

According to the report, global average sea surface temperatures (SSTs) remained ‘persistently and unusually high’, reaching record levels for the time of year from April through December.

High SSTs in most oceans, and in particular in the North Atlantic, played an important role in the record-breaking global temperatures.

The main long-term factor for high ocean temperatures is the continuing increase in concentrations of greenhouse gases.

Rising temperatures and more extreme weather events: How is Europe’s tourism industry coping?

Climate stripes: Dark red line added after 2023 smashed temperature records

But an additional contributing factor in 2023 was the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

ENSO is a natural climate phenomenon that sees temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean switch between cooler (La Niña) and warmer (El Niño) than average conditions.

These ENSO events influence temperature and weather patterns around the world. After La Niña concluded in early 2023 and El Niño conditions began to develop, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) declared the onset of El Niño in July. And conditions continued to strengthen through the rest of the year.

The unprecedented SSTs were also associated with marine heatwaves around the globe, including in parts of the Mediterranean, the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean and North Pacific, and much of the North Atlantic.

Antarctic sea ice is at a record-low

2023 was also significant for Antarctic sea ice as it reached record lows across eight months of the year. Both the daily and monthly measurements reached all-time lowest levels in February 2023.

In the Arctic, satellite records showed that sea ice extent at its annual peak in March ranked amongst the four lowest for the time of the year. The annual minimum in September was the sixth-lowest.

“The extremes we have observed over the last few months provide a dramatic testimony of how far we now are from the climate in which our civilisation developed,” says Buontempo.

“This has profound consequences for the Paris Agreement and all human endeavours.”

Greenhouse gas level break records

Greenhouse gas concentrations in 2023 reached the highest levels ever recorded in the atmosphere according to C3S and the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS).

Carbon dioxide concentrations in 2023 were 2.4 parts per million (ppm) higher than in 2022 and methane concentrations increased by 11 parts per billion (ppb).

For 2023, the annual estimate of the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide is 419 ppm, and for methane, the concentration is 1902 ppb.

The rate of increase of carbon dioxide was similar to the rate observed in recent years but - though still high - methane increases were lower than in the last three years.

Mauro Facchini, head of earth observation for the European Commission, says previous work by C3S in 2023 meant the report was not expected to provide "good news".

"The annual data presented here provides yet more evidence of the increasing impacts of climate change."

He adds that, as the EU continues with its commitment to reduce emissions by 55 per cent by 2030 (now just six years away), "the challenge is clear".