The tricky business of weather prediction: Why forecasters sometimes get it wrong

No matter what the TV weatherman says, it’s probably always worth packing an extra jumper or maybe even that umbrella you don’t think you’ll need.

It’s less common than it used to be, but the weather forecast isn’t always right.

Just ask anyone living in Melbourne. In 2017, in one of the more famous recent cases of the Bureau of Meteorology getting it a bit wrong, Victorians were told to brace for a biblical storm with severe weather warnings issued and 7.4 million text messages sent out warning residents of flooding.

In the end it passed Melbourne and surrounding areas with little excitement but later drenched the north of the state. Many were left wondering what all the fuss was about, forcing the Bureau of Meteorology to defend its forecasting.

The physics and technology of weather forecasting have advanced significantly in recent years but perfect accuracy remains a quixotic notion.

In the age of satellites and super computers we’ve got more observational data and more power to crunch it than ever before.

As a result we can now predict seven days ahead with about the same accuracy as we could to three days at the turn of the century.

"Fifteen years ago when I started at the BoM, we’d get one satellite image every hour," senior bureau forecaster Steven McGibbony told Fairfax in May.

"Some of the older forecasters here in the '90s said we’d get one every six hours. We now get a satellite image every 10 minutes."

What goes into weather forecasting?

When talking about the weather, we’re talking about the state of the atmosphere above us, from large-scale features that move around the planet like low pressure systems and cold fronts, to smaller scale features like sea breeze circulations and thunderstorms.

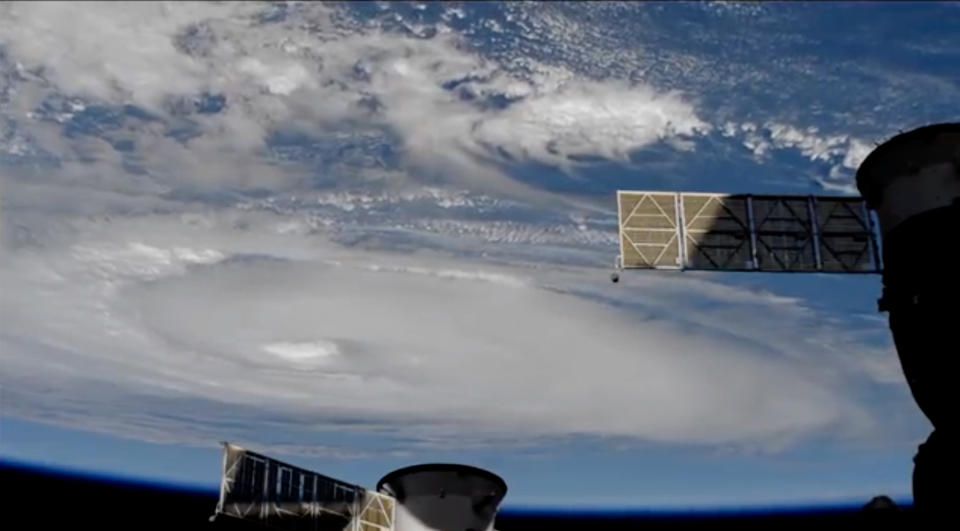

Measurements are taken on the ground, in the air via air balloons and in outer space which are fed into models to help determine factors that are going to impact on things like surface temperature, wind and precipitation.

The collection process is an international effort, with Australia working closely with Japan to provide a patchwork of data. But it’s still that: a patchwork of data and algorithms which are interpreted by human experts. To be perfectly accurate every time, scientists would need near constant data from every single point on the planet.

For example in 2015, the BoM conceded a $77 million super computer and upgrades to a Japanese satellite that we rely on would not replace the need for basic radar data for an important grain growing area of Victoria.

It might sound like a steep cost, but it makes sense to pump money into weather forecasting because it plays an important role in agriculture, energy management, aviation, and disaster resilience.

A 2017 study found “for every dollar spent on delivering Bureau [of Meteorology] services, these services return a benefit of $11.60 to the Australian economy.”

Why the forecast can sometimes get it wrong

Despite forecasting techniques coming along in leaps and bounds, the chaotic and mercurial nature of weather means sometimes things don’t pan out exactly as predicted.

And sometimes, the BoM’s models even spit out contradicting information.

"One may suggest the cold front will come early, another may say it’ll be in the afternoon. In that scenario, we look at it and consider which model has been performing better lately, and weight our forecast towards that model," Mr McGibbony told Fairfax.

On the rare occasions they do get it wrong, it tends to be extreme weather events like thunderstorms, and often in summer.

At that time of year there is typically plenty of moisture and instability to help fuel the development of scattered showers, and thunderstorm triggers can be particularly hard to pinpoint.

"In summer you’ve got more energy in the atmosphere with the sun producing more heat," Mr McGibbony explained.

"For example, with a cold front, being slightly inaccurate makes a big difference. If you’ve got 40 degrees on one side of the front and 20 degrees on the other, a slight disagreement in the models may mean you’re not sure if the heaviest rainfall will be in the late morning or early afternoon."

The growing role of tech in climate and weather prediction

According to a new study this week in the journal, Nature, artificial intelligence (largely a catch-all term for self-improving algorithms) is learning how to predict El Niño weather patterns.

The climate driver is part of a natural cycle and is known for bringing reduced rainfall and warmer temperatures to Australia, but scientists have struggled to predict its arrival more than a year out.

However the AI system has shown promise at predicting an El Niño event from 18 months out.

It highlights the growing role of emerging technology as nations harness their growing computing power to pre-empt Mother Nature.

In December 2016, the British Met Office completed the final installation of what it said was then one of the most powerful supercomputers in the world.

The computer system is able to make more than 14,000 trillion arithmetic operations per second, allowing it to make 215 billion weather observations from all over the world every day.

The other world leader in the field is the United States, but even the world’s biggest tech power can’t get it right all the time.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a seven-day forecast can accurately predict the weather about 80 per cent of the time and a five-day forecast can accurately predict the weather about 90 per cent of the time.

The further you look into the future, the less accurate it will be with studies suggesting a two-week limit to weather forecasting.

A 10-day forecast or longer, the NOAA says, will only be right about half the time.

Do you have a story tip? Email: newsroomau@yahoonews.com.

You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter, download the Yahoo News app from the App Store or Google Play and stay up to date with the latest news with Yahoo’s daily newsletter. Sign up here.