'Pity the merely rich': Why this man has walked 16,000km around the world for seven years

They say you should never judge a person until you’ve walked a mile in their shoes. Adhering to this philosophy, there is perhaps no man more equipped to judge his fellow man or woman than Paul Salopek.

As you’re unwrapping your presents or chowing down on ham and prawns this holiday season, spare a thought for him, and more importantly, the less privileged people he walks alongside as he traverses the globe on foot.

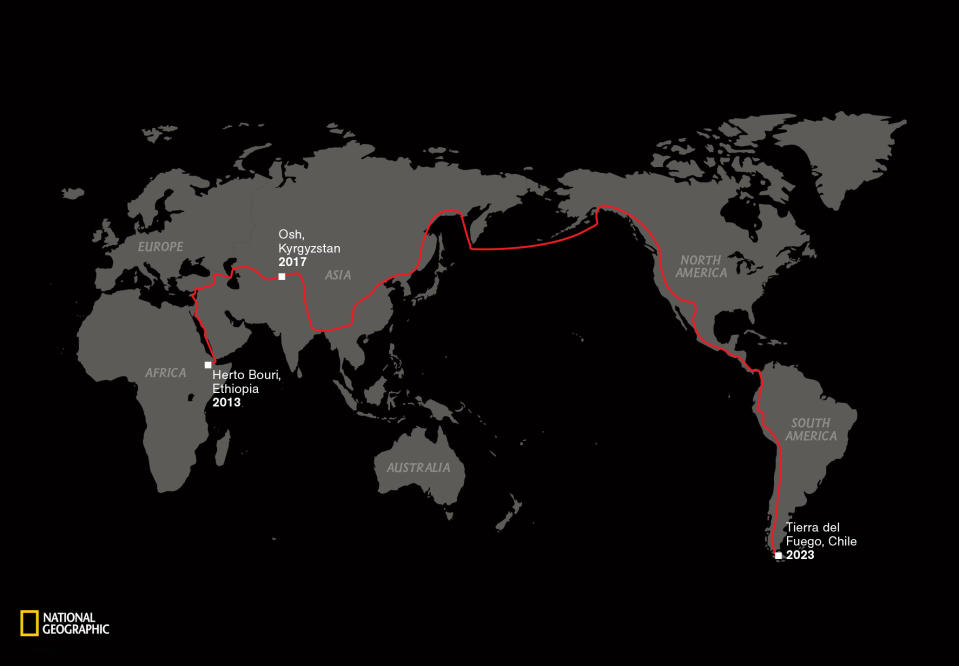

The two-time Pulitzer Prize winning writer and journalist will be somewhere in Myanmar. He has spent nearly the past seven years walking with migrants across Africa, skirting Europe, and through Asia, in a journey to trace the the meandering path early humans travelled from “the cradle of civilisation” as they spread out from Africa and first colonised the globe.

The mother of all treks began in Ethiopia in 2013 and as the new year is ushered in, Mr Salopek will be somewhere passed the midway point of his journey.

He refers to himself as a “privileged walker” but those he joins along popular migratory routes are typically fleeing conflict or poverty. While the American is in search of stories that reflect the eternal truths of the human experience, they are in search of somewhere safer than whence they came, and ultimately a chance at the prosperity they see plastered across their social media streams.

As a writer for National Geographic, Mr Salopek chronicles what he sees and the people he meets along the way.

“In Djibouti I have sipped chai with migrants in bleak truck stops. I have slept alongside them in dusty UN refugee tents in Jordan. I have accepted their stories of pain. I have repaid their laughter,” he wrote recently.

Many of the burgeoning diaspora that move around the globe are residents pouring out of troubled spots in Africa and the Middle East, with many hoping to ultimately land in Europe.

Figures from the UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs put the growing number of international migrants in 2019 at 272 million, outpacing the growth rate of the world’s population. By 2050, estimates suggest there could be as many as a billion migrants due to climate change alone.

As a wave of anti-immigrant populism continues to take hold in many parts of the western world, it’s hard not to feel like the state-based international system of migration is breaking under the weight of this reality.

“I think we're at a fulcrum point in our history, given the information revolution and our numbers, where trying to bottle-up human aspiration and yearning behind walls, or restrictive visas, or island prisons is no longer a very sustainable long-term migration policy,” Mr Salopek says.

“More people are on the move now than ever before in the recorded history of Homo sapiens. People who don't have stuff know it more clearly than ever before. The people who have stuff are afraid (and) gripped by anticipatory loss.”

Travelling the world on foot has allowed Mr Salopek to witness the best parts of humanity while also seeing the consequences of mankind’s worst impulses as police and border control agents herd up those without the requisite identification.

The first migrants he encountered were dead. Bodies scorched by the sun in one of the hottest deserts on earth, in an area known as the Afar Triangle which overlaps the borders of Eritrea, Djibouti and the entire Afar region of Ethiopia. It was impossible to know who they were or where they were going.

“There have been hard days all along the trail, particularly days hazardous to emotional health because of the volumes of human pain on open display in some landscapes,” Mr Salopek says.

“like the physical want in places like Djibouti or India, or the millions of Syrian refugees washed up in the Middle East, or the uniformly diminished status of women in virtually every society I've walked through, to name just a few.”

He travels with the absolute bare essentials and almost every morning he wakes, he has no idea where he will be sleeping that night.

“My discomforts are absurd and I'm doing this voluntarily,” he says.

“I'm not much interested in gear, and I grow less interested every day.”

To date, he has walked more than 16,000 kilometres but insists his body is holding up just fine. “Walking helps keep it that way,” he says.

“Moving on foot 15 miles or so a day is what we're evolutionarily designed for. Sitting down is what kills you.”

The writer is also keen to avoid the trappings of another aspect of modern life. The information age has brought untold benefits to societies around the world but is fundamentally changing the way we interact and organise ourselves. At least for some, it seems the constant input comes with a growing disquiet.

“We consume more information now than ever before in our 300,000-year-long history. But all this data overwhelms our ability to process it, to make genuine sense of it.”

The 24/7 media cycle and the smartphones in our pockets which incessantly ping us with the latest headlines serve to infantilise society by arousing and immediately gratifying powerful emotions such as hate, love, anger and envy, he says.

“The walk is a journey towards quieter but hopefully deeper rewards.”

The ultimate destination for Paul Salopek is the southern tip of South America – Tierra del Fuego. A destination he estimates he will arrive at in about five or six years, give or take.

When asked what has surprised him over the course of his journey so far, he expresses a truth we all know on some level, but seldom organise our lives around: “How little we truly need,” he says.

“And how much more real – grounding, solid, lasting – the rewards of human relationships are than the material gimcracks we try to replace them with.

“Pity the merely rich,” he says.

Do you have a story tip? Email: newsroomau@yahoonews.com.

You can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter and download the Yahoo News app from the App Store or Google Play.