Unknown Mortal Orchestra: ‘If I didn’t have kids, then I wouldn’t be talking to you now’

I know there are things wrong with my music,” says Ruban Nielson, vocalist and guitarist of psych-rock band Unknown Mortal Orchestra. “My mixing is bad, and my recording is purposefully amateurish sometimes, but I’m trying to concentrate on how to deliver something that feels worth saying.” The New Zealand-Hawaii singer is calling on Zoom from his dimly lit basement studio in Portland, where it’s just begun snowing. For Nielson, perfection has always taken a backseat when it comes to the band’s distinctive DIY sound, which he finds impossible to sum up. “I’ve always made up genre names,” he tells me, offering up suggestions like “Dad-wave” and “trouble-gum”. “Depression funk” is another fan-favourite.

If the latter is accurate, then UMO could now be considered masters in mental health music. The band are on album number five. The latest, V, a double offering, is stuffed full of warm, homemade instrumentals and fuzzy future classics that could only come from the creators of their once shed-crafted sound. Experts in alternative ambivalence, UMO are innovators of the bittersweet, often grouped with previous touring partners, Foxygen. The band – primarily Nielson and bassist Jake Portrait – began in 2010 in Auckland, when the former anonymously released a Soundcloud track into the wild. Since then, their spirited music has gained critical acclaim, and helped them sell out world tours. Just last month, UMO celebrated 10 years of their 2013 debut album. The now classic || included riffy and reminiscent tracks like “So Good At Being In Trouble” – now gold.

“I couldn’t make that record again,” says Nielson. “It’s so specific to what I was going through at that time; all the limitations and desperation of, ‘Who am I? What am I doing?’” he says. “It’s all baked into the record itself. I can hear it.” || was created during a tempestuous time spent sofa-surfing and navigating “quite a bad drug problem”. Eventually, though, Nielson says, he had a realisation. “At some point I am going to have to decide if I’m just going to change and move on to the next chapter in my life or if I’m gonna die,” he recalls thinking, explaining that many of his close friends “didn’t make it into their forties”. It was his children who pulled him “back from the edge”. Nielsen looks sincerely at me through the camera, illuminated by his daughter’s selfie ring light. “I think if I didn’t have kids, then I wouldn’t be talking to you now,” he admits. “I was fine with sacrificing myself. I just wasn’t fine with sacrificing other people.”

Nielson has learnt a lot in the last decade. He’s learnt that the band lifestyle can lead to one becoming a “self-obsessed s***” – and he’s learnt that family isn’t only his reason to survive, but to really live. “I would throw away any amount of glory just to get the approval of my children,” he laughs, a little self-consciously. Nielson, his wife, Jenny, and their two children divide their time across Portland, Palm Springs and Hawaii, where Nielson’s mother lives. Up until recently, he was on a break from music, choosing instead to invest time into being a good son and father. The pandemic, however, resulted in a series of “tragedies” for his relatives that reminded Nielson why he got into this career in the first place. Making music is how he “copes with life”.

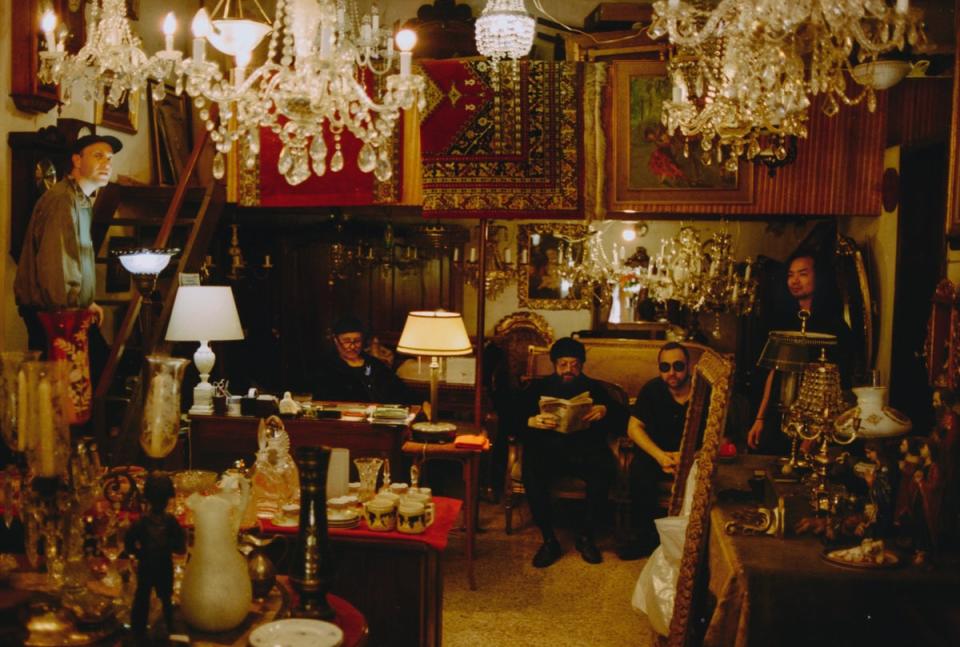

That’s when UMO’s new album V was born. Music and family collided, and inadvertently the latter became central to the songs, which were recorded in Palm Springs together with his brother, father, and long-term bandmate Portrait. “We didn’t come out of that period the same,” he tells me. In fact, Nielson thinks they emerged from it better. “We thought, if we don’t come out of this as stronger and less selfish people, then all of this is just another big tragedy for our family.”

Tragedies considered, Nielson felt it important that the album still be uplifting. “I didn’t want to make a sad record because it’s such a sad time,” he says. “We wanted to ease the pain and to bring light to the situation.” Tracks lyrically teleport listeners to the shushing sways of palm trees, sparkling seas and sandy skin. That said, as with most of UMO’s work, those sun-kissed sonics are shadowed by a little darkness, as heard in the nuances of the nostalgic “That Life”. “When is life not like that?” says Nielson of the bittersweetness inherent to his music. “How can you actually be happy if you’re not acknowledging these dark things?” Given the circumstances surrounding the album, mortality inevitably became a theme for V. But instead of weighing him down, it gave him a carpe diem approach to life and creation. “I think the baseline that I’m working from is constantly thinking about death, and always using it as an excuse to be reckless,” he laughs.

The singer has always had an impending sense of doom about the world around us. “UMO started in this Obama-era, and everyone was in this daze. At that time, everybody seemed to be like, ‘Oh my god, life is so great – but I was already very morbid.” As Nielson got older, he felt a switch. “Now the baseline is for everybody to feel pessimistic,” he chuckles at the bleakness of the situation. “You know, politically disillusioned, constantly mindful of death and stuff like that.”

It’s ironic, then, that Nielson feels less morbid now than before. The veil of pretence has lifted and he’s relieved. “That ambient feeling that we’re heading off a cliff is now kind of established as real,” he suggests. “This is when you can start to get real about stuff and fix things.” Nielson believes now is the time to live life to the full. “If we’re all going to die, we should make it count. We should party, we should look after the people we love, we should tell our moms, we love them! If it’s really all over, it’s not the time to be depressed.”

Although there are clues, Nielson isn’t sure what the songs on V are about just yet. In fact, it always takes him one or two years to figure out the true meaning of his music. “I think the reason I’m really addicted to making music is because it’s such a weird, mysterious process.” He’s started to think of the writing process as a type of “religion”. “It’s a cheesy word, but it’s kind of like you’re channelling something,” he muses. “Like what you’re creating is coming from your subconscious or a higher power. Sometimes when I write, I think, ‘How did I even do that?’ I don’t feel 100 per cent the author of it. I feel like I just was there and accidentally did it.” He wonders if this means his songs belong to others, and recalls anecdotes from shows at which fans have described acute situations in their own lives that his music perfectly articulates. He asks himself, “What if the song is actually about them? What if I’m just the person that delivers it?”

I like the idea of being a successful musician, but I don’t like the idea of people discussing me

Ruben Nielson

One particular album, though, was written about something very specific in Nielson’s life. The 2015 record Multi-Love centred around Nielson’s polyamorous relationship with his wife with another woman. The specifics were subsequently detailed in a Pitchfork article, which somewhat sensationalised the relationship. The subject was made bigger than the music, and the woman involved felt wronged by the revelation. “I had to learn the hard way that [my life] is not entirely mine to talk about,” he says. “I didn’t think that anyone would care enough for it to be an issue.” I ask Nielson if the experience has been lyrically stifling. “I realised I have to be more skilful about giving as much of myself as I can… without dragging other people in ways that they never signed up for,” he admits. “I like the idea of being a successful musician, but I don’t like the idea of people discussing me; that’s not ever why I got into this. It always feels like you’re trying to negotiate something: how much success do you want, versus what the price is?”

He may have no desire for the limelight, but the stage is a special place for Nielson. “I walk out there and then some other part of me takes over,” he says. “I don’t have a single thought; I’m the purist version of myself.” That’s an addictive feeling. “It’s almost like I’m a different person – you get to escape your ego and yourself.” Escape is imminent for Nielson. UMO will soon hit the road for their mammoth tour across the States and Europe. In September, the band will end with a headline slot at End of The Road festival.

The tour isn’t without concerns, though. A few months ago, a nerve compression in Nielson’s left hand left him unable to move it; he has had to attend daily physio just to play his guitar. Always finding the silver lining, Nielson says the injury has shifted his focus from achieving perfection to just being able to play the parts. Now, without the pressure, he can concentrate on conveying something meaningful. That’s all he’s ever wanted.

Unknown Mortal Orchestra’s new album ‘V’ is out now via Jagjaguwar