A millennium of war stories in Bayeux

Steve McKenna is mesmerised by a millennium of war stories in Bayeux.

The French schoolchildren beside me are on tiptoes, peering over the display — they are, it seems, utterly bewitched by it. They’re no more than seven years old, the age I was when I first learned about the Bayeux Tapestry. Nearly three decades on, those classroom memories come flooding back to me as I admire this medieval comic strip in the “flesh” for the first time.

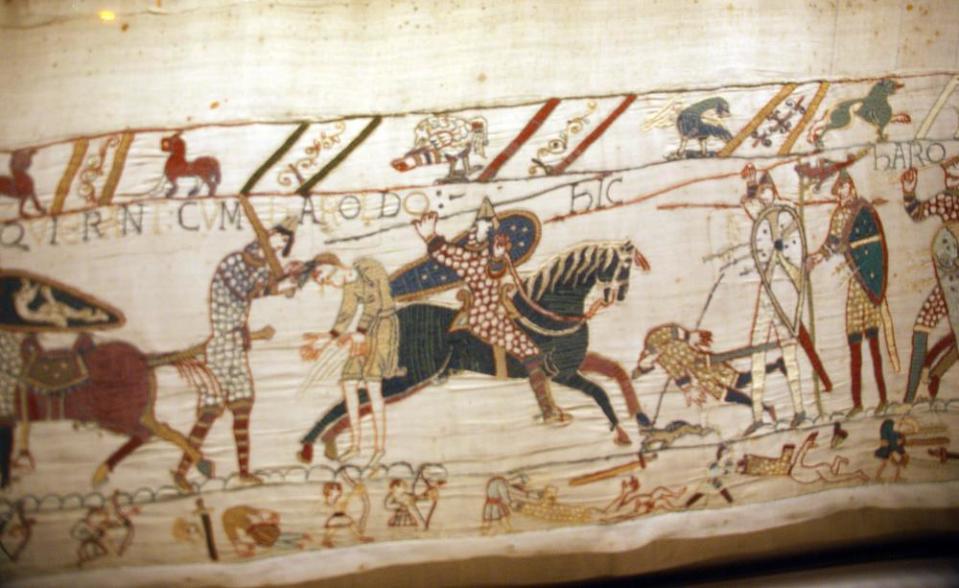

Etched on to a 70m-long linen canvas, this tapestry — one of the finest pieces of art from Europe’s Middle Ages — tells the story of the Norman conquest of England, and the conflict between the armies of William, the Duke of Normandy, and Harold, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England.

William famously triumphed over Harold in the Battle of Hastings in 1066, earning the crown of England and the moniker “the Conqueror”. It was a step-up from his previous nickname, “William the Bastard” (he was the child of an affair between his father, Duke Robert the Magnificent, and a tanner’s daughter; William’s illegitimacy meant he had initially struggled to gain the respect of his peers).

Housed in a former 18th-century seminary at the heart of Bayeux, the tapestry is actually an embroidery — because it’s embroidered, rather than woven. It’s thought to have been commissioned by Odo, the bishop of Bayeux and William’s half-brother, and exquisitely crafted by seamsters in Canterbury, England (though some argue it was really the brainchild of Queen Matilda, William’s wife, and made in France). The tapestry’s richly detailed scenes are summarised, step by step, on a multi-language audio guide, whose English version comprises commentary from a well-spoken English gent, as violin music — the kind you’d hear at a medieval-style banquet — throbs in the background.

The tapestry’s first half traces the roots of the conflict between William and Harold. Edward the Confessor, the ageing, childless king of England, chose William — a distant cousin — to be his successor, and it was Harold — the Count of Wessex and the second most powerful man in England after the monarch — who sailed to Normandy to swear an oath of allegiance to the Norman duke. After Edward’s death, however, Harold seized power himself. Enraged, William mustered thousands of troops, and, determined to confront his rival, sailed across the English Channel in a fleet of newly built dragon-headed ships (the design of which was a nod to the Normans’ Viking ancestors).

All this political intrigue, allied with the tapestry’s gripping battle scenes — featuring a slew of armoured troops, tumbling horses and flying arrows (including the one that may or may not have ended up in Harold’s eye) — brings to mind Game of Thrones. Indeed, in interviews, the creator of that epic fantasy, George R.R. Martin, admitted that the horrific violence in his stories was inspired by gruesome medieval tussles such as the English civil wars and the Battle of Hastings.

The upstairs part of the tapestry museum offers more information on this UNESCO-designated “Memory of the World”, which weighs close to 350kg. Displays also assess King William’s impact on English culture, language and identity, exhibiting maps and models of the numerous towns, castles and cathedrals constructed during the Norman era. It was under William’s reign that the Tower of London was built.

While Bayeux is world-renowned for its tapestry, it’s also an important hub for tourists interested in World War II. Next to the town’s British military cemetery, the Memorial Museum of the Battle of Normandy is one of the region’s best war-themed attractions, detailing how the Allies drove German forces out of Normandy in the 10 weeks that followed the Allied landings on D-Day (June 6, 1944).

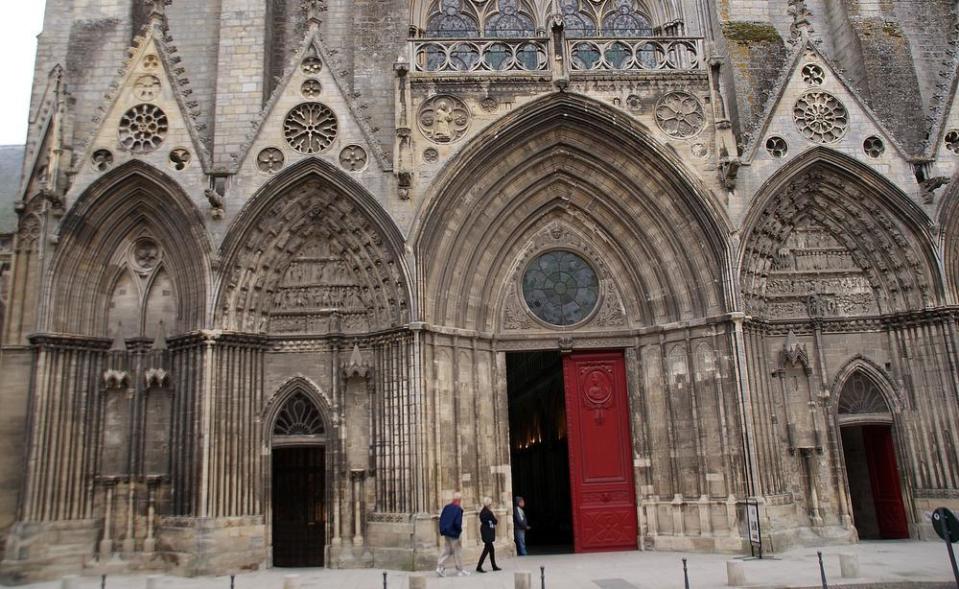

Unlike many places in Normandy, Bayeux — the first French town to be liberated from nazi occupation — survived World War II virtually intact (physically, at least) and its pretty cobblestoned centre, hedged around a huge spired Gothic cathedral, is a joy to explore on foot. Visitors are charmed by the town’s cluster of photogenic timber-framed buildings, and there’s a good selection of souvenir shops, cafes, restaurants, hotels and guesthouses.

Tucked 7km inland from La Manche (as the French call the English Channel), Bayeux is a handy base for exploring the D-Day landing beaches, which stretch around 100km, from Ouistreham, the port of Caen, to Quineville by the Cherbourg Peninsula.

You could probably cover Sword, Juno, Gold, Omaha and Utah beaches in a (long) day at a push, but it’s worth giving yourself more time to visit these imagination-stirring strips of sand — as well as inland sights such as Pegasus Bridge, a strategically important point captured by British airborne troops in the hours prior to the D-Day sea invasion. With public transport sparse, you’ll either need to sign up for a guided tour or hire your own set of wheels.

There are so many war memorials, museums and cemeteries in Normandy — and so much bravery, sacrifice and futility to ponder — that you could easily spend a week on a conflict-themed tour of the region.

I found that three incredibly absorbing days sufficed — for this trip anyway.

FACT FILE

Entry to the Bayeux Tapestry Museum is €9 ($12.50), with concessions €7.50 and €4 for children over 10. Under-10s enter free. You can buy a joint ticket for the tapestry museum and the Memorial Museum of the Battle of Normandy for €12 (€10 concessions). bayeuxmuseum.com.

For more information on Bayeux, see bayeux-bessin-tourisme.com.

For an overview of the Normandy region, see normandie-tourisme.fr.