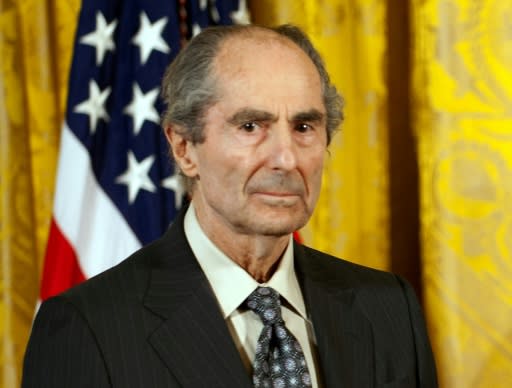

Giant of American literature, Philip Roth, dead at 85

Philip Roth, a giant of US literature whose work explored what it meant to be American, male and Jewish, was a towering figure among 20th century novelists whose five-decade career won him legions of awards around the world. He died on Tuesday in Manhattan of congestive heart failure, the Wylie Agency told AFP, only six years after he announced his retirement. He was 85. It marked the end of an extraordinary career for an author who found fame with the wildly graphic "Portnoy's Complaint" in 1969 and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1998 for "American Pastoral," whose "Plot against America" found renewed significance under the Donald Trump presidency and published "Nemesis," his final novel, in 2010. Roth was widely considered the last living great, white, male American novelist, who along with Saul Bellow, Norman Mailer and John Updike helped define what it meant to be American in the latter half of the 20th century. "The death of Philip Roth marks, in its way, the end of a cultural era as definitively as the death of Pablo Picasso did in 1973," wrote New York Times book critic Dwight Garner on Wednesday. His more than two dozen novels boldly explored male lust and sexual temptation, ageing and mortality, and while he was not religious he powerfully mined the Jewish-American experience, drawing on his upbringing as the son of first-generation middle-class Americans in New Jersey. "You can't invent out of nothing, or I can't certainly," he said in a 2011 documentary. "I need some reality, to rub two sticks of reality together to get a fire of reality." Roth won two National Book Awards, two National Book Critics Circle Awards, three PEN/Faulkner awards and the Pulitzer -- but the Nobel prize evaded him. He collected the Man Booker International Prize for lifetime achievement in fiction in 2011, followed the next year by Spain's Prince of Asturias award for literature and in 2015, France presented Roth with the insignia of Commander of the Legion of Honor -- a laurel the author called "a wonderful surprise." - 'American Pastoral' - Two years after he published "Nemesis," about a 1944 polio epidemic, he stunned the literary world by announcing that he would no longer write fiction. "Right now it is astonishing to find myself still here at the end of each day. Getting into bed at night I smile and think, 'I lived another day'," he told The New York Times in an interview earlier this year. A prolific essayist, critic and novelist, the 1990s were the height of his productivity, exemplified by his widely admired trilogy -- "American Pastoral" (1997), "I Married a Communist" (1998) and "The Human Stain" (2000). "By 2010 I had a strong suspicion that I'd done my best work and anything more would be inferior," he told the Times in January. "Every talent has its terms -- its nature, its scope, its force; also its term, a tenure, a life span... Not everyone can be fruitful forever." Roth's 2004 novel "The Plot Against America" was thrust back into the public eye following Trump's election. It imagines Franklin D. Roosevelt being defeated in 1940 by Charles Lindbergh, an aviator with pro-Nazi leanings, which led some critics to draw comparisons with Trump's populist sweep to power. But Roth downplayed a parallel, saying that while Lindbergh was racist and anti-Semitic, he was also a hero for his solo trans-Atlantic flight. "No one I know of has foreseen an America like the one we live in today," he told the Times. "Trump," he said "is a massive fraud, the evil sum of his deficiencies, devoid of everything but the hollow ideology of a megalomaniac." - 'How far I could go' - Philip Milton Roth was born March 19, 1933 in Newark, New Jersey, the grandson of European Jews who migrated to the United States. Growing up in a middle-class home, his father was an insurance manager and his mother, a secretary turned homemaker. He graduated from Bucknell College in Pennsylvania in 1954 and did graduate studies at the University of Chicago. He published his debut collection of short stories, "Goodbye, Columbus," at the age of 26, a look at the materialist values of the immigrant milieu. Although the work earned huge praise, and won the National Book Award, some critics felt betrayed by what they saw as an unflattering depiction of the Jewish-American experience. "I don't have a religious bone in my body," Roth once told CBS News. "When the whole world doesn't believe in God, it'll be a great place." It was his third novel, "Portnoy's Complaint," that brought fame with its comic description of frenzied sexual angst facing a young middle-class New York man burdened with a domineering and possessive mother. "I was very curious as a writer as to how far I could go," he said in one interview. "What happens if you go further?" It's best, certainly in the early stages of a book, to abandon self-censorship." The book topped the Times best-seller list and turned its reclusive author into a celebrity -- an uncomfortable position that he would later satirize in novels "Zuckerman Unbound" (1981) and "Operation Shylock" (1993). Readers have long argued over the true level of autobiography in Roth's novels and the character Nathan Zuckerman, whose passage from aspiring young writer to socially compromised literary celebrity Roth traced in five novels. Feminists have also criticized Roth's portrayal of women. "If in Bellow misogyny was like seeping bile, in Roth it was lava pouring forth from a volcano," wrote Vivian Gornick in Harper's Magazine in 2008. Roth's personal life was dragged into the spotlight following his messy breakup with British actress Claire Bloom, who painted a grim picture of life with her ex-husband in the 1996 memoir "Leaving a Doll's House." Reportedly infuriated, Roth exacted revenge by caricaturing Bloom as a poisonous character in "I Married a Communist." burs/jm/ec US novelist Philip Roth won the 1998 Pulitzer Prize for fiction for "American Pastoral" A contemporary of Don DeLillo, Saul Bellow and Norman Mailer, the late Philip Roth was the doyen of a whole literary era -- but the Nobel prize evaded him�