Scientists pinpoint where life might once have flourished on Mars

The most likely place for life to have flourished on Mars is miles below the surface, scientists believe, as geothermal heat melted thick ice sheets billions of years ago.

Alien life, if it ever existed on Mars, may have followed liquid water deep into the interior of the planet, existing deep below its surface.

While many features on Mars’s surface hint at water, the loss of the planet’s magnetic field and chilly temperatures meant life was more likely to survive beneath the surface, Rutgers University scientists have said.

Their research was published in Science Advances.

Lead author Lujendra Ojha, of Rutgers University-New Brunswick in New Jersey, said: “At such depths, life could have been sustained by hydrothermal (heating) activity and rock-water reactions.

“The subsurface may represent the longest-lived habitable environment on Mars.”

Watch: To find life on mars, experts say we need to start looking under its surface

Read more: Mysterious “rogue planet” could be even weirder than we thought

Over time, our sun has gradually brightened and warmed the surface of planets in our solar system.

About four billion years ago, the sun was much fainter, so the climate of early Mars should have been freezing.

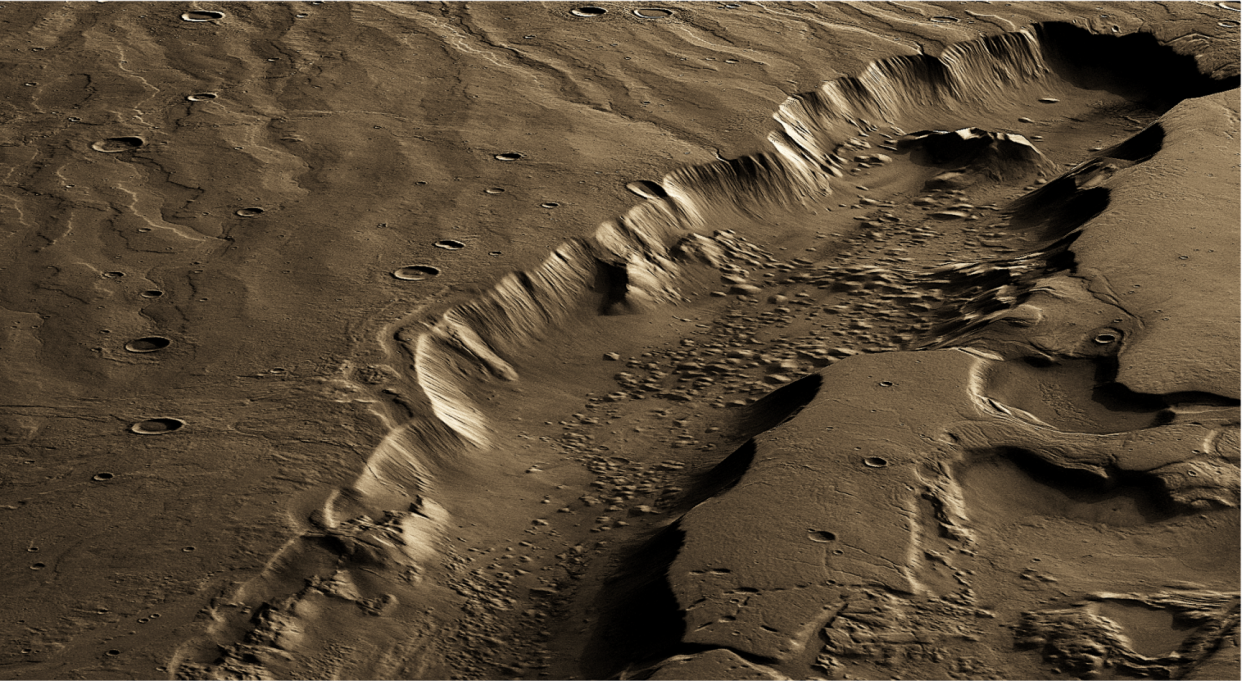

But the Red Planet’s surface has many geological indicators, such as ancient riverbeds, and chemical indicators, that suggest it had abundant liquid water about 4.1 billion to 3.7 billion years ago (the Noachian era).

This apparent contradiction between the geological record and climate models is known as “the faint young sun paradox”.

Ojha and his team believe that geothermal heating, similar to what’s found on Earth, could resolve the paradox.

Read more: Astronomers find closest black hole to Earth

Ojha said: “Even if greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and water vapour are pumped into the early Martian atmosphere in computer simulations, climate models still struggle to support a long-term warm and wet Mars.

“I and my co-authors propose that the faint young sun paradox may be reconciled, at least partly, if Mars had high geothermal heat in its past.”

On rocky planets like Mars, Earth, Venus and Mercury, heat-producing elements such as uranium, thorium and potassium generate heat via radioactive decay.

It means liquid water can be generated through melting at the bottom of thick ice sheets, even if the sun was fainter then than it is now.

On Earth, for example, geothermal heat forms subglacial lakes in areas of the West Antarctic ice sheet, Greenland and the Canadian Arctic.

It’s likely that similar melting may help explain the presence of liquid water on cold, freezing Mars four billion years ago.

The scientists examined various Mars datasets to see if heating via geothermal heat would have been possible in the Noachian era.

They showed that the conditions needed for subsurface melting would have been ubiquitous on ancient Mars.

Watch: Astronaut shows glimpse of earth from space