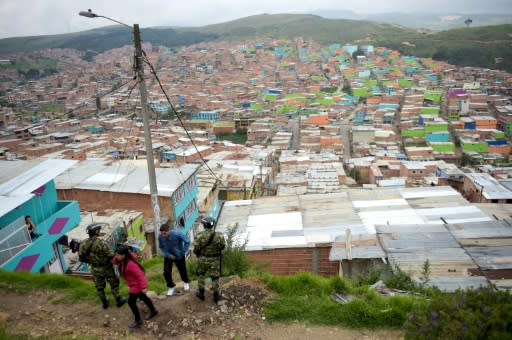

On the edge: the forgotten poor left by Colombia's war

They live in shantytowns that overlook Bogota -- hundreds of families who fled the bloodshed in rural Colombia during decades of civil war for the relative safety of the country's cities. A year and a half after the government signed a peace deal with the leftist Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the poor still languish on society's margins. They are the forgotten ones. Jose Pineda lives with his family lives in the ramshackle Ciudad Bolivar slum on the outskirts of Bogota, which seems to hang off the gray, chilly Andes mountainsides. El Ensueno, their neighborhood, is perched at the summit. Most of the people in El Ensueno -- 600 households in all -- are victims of the conflict. Once thrown off their land, they have built shacks here, and constantly fear eviction. Men, women, and children live in cramped conditions. Mud is everywhere. Water trickles down from the mountains above, and power is siphoned off from bootleg connections. If buses ever come, few have the money to afford a ticket. "Colombia is divided between those who have a real house, and those of us who have a shack with a tin roof... those who eat when they want to, and those of us who make do with one meal a day," said the 50-year-old Pineda, a father of three. The country is only just emerging from five decades of war, and even that isn't fully over -- remnants of rebel forces still battle for control of the lucrative drug trade. Those years of conflict exacerbated poverty in Colombia, where the rich-poor divide is among the widest in the world, alongside Haiti and Honduras, according to the World Bank and the United Nations. Nearly eight million people have been displaced by the violence, which has pushed thousands "towards cities, generating pools of misery" on the fringes, Jorge Restrepo, a professor at Javeriana University and author of the study "Conflict and Poverty in Colombia," told AFP. The conflict -- which drew in leftist guerrillas, paramilitary groups and state forces -- left about 260,000 people dead. - Struggle to survive - Pineda fled the country's southeast four years ago, after being brutally interrogated about his alleged ties to the FARC, whose members surrendered their weapons after the peace deal. The group is now a political movement. But now, he is just one of the masses living on the edge. Their fate depends on the ability of Colombia, Latin America's fourth-largest economy, to truly embrace peace and keep violence from reaching urban areas when current President Juan Manuel Santos leaves office. The country will soon elect a new leader, with the first round scheduled for May 27, and the runoff for June 17. Oscar Lezama, a former police officer who fled to Bogota in 2012, lives in El Ensueno with his wife and four children. "The war forced us from the countryside to the city. We have to fight just to have five square meters," said the 48-year-old, his frustration palpable. While the peace deal helped reduce the staggering death toll of 3,000 a year seen during the war, it has also divided Colombians. Some have criticized the amnesty offered to former rebels, who have since been rehabilitated and allowed to enter politics. If Colombia's right-wing wins the presidency, it has pledged to modify the accord. In areas like Ciudad Bolivar, home to 700,000 people, residents are angry that peace did not in any way improve their prospects. Santos's administration, in power since 2010, launched an ambitious program of land restitution, but without specific plans for those forced into the cities. - Fresh violence - Poverty in terms of income in Colombia has decreased from 37.2 percent in 2010 to 26.9 percent in 2017. However, that still means that out of a population of almost 50 million, 13 million are poor. Without "more ambitious programs," poverty will be "a permanent factor fueling violence, and perhaps even a resumption of war," said economist Eduardo Sarmiento. In El Ensueno, armed factions are taking advantage of the power vacuum left by the FARC, with drug dealers targeting schools. Five illegal organizations including the National Liberation Army (ELN) -- the country's last active rebel group -- operate within Ciudad Bolivar, according to Colombia's human rights ombudsman. The violence that persists in several areas could lead to further displacement, fueling poverty, which has become a ticking time bomb in Colombian society. Deysi Garcia, a mother of five children, almost lost her farm in Viota, 90 kilometers (55 miles) from Bogota. Paramilitaries occupied her land, where two bodies were later found. Freed from prison, she succeeded in retaining her coffee plants but must also work as a maid. Her farm, because of its isolated location, cannot turn a profit. "Customers pay very little, and it doesn't cover the cost of production," said the 38-year-old widow. A Colombian boy stands in the El Ensueno neighborhood of the Ciudad Bolivar slum on the edge of Bogota -- 18 months after the government signed a peace deal with FARC rebels, the poor still languish on society's margins A woman holding a baby exits her home in El Ensueno -- there is mud everywhere Jose Pineda fled southeast Colombia four years ago after being brutally interrogated about his alleged ties to the FARC. He now lives in poverty in Ciudad Bolivar Colombian soldiers stand guard at the Ciudad Bolivar slum outside Bogota -- it is home to 700,000 people Many in Ciudad Bolivar live in makeshift homes