Cancer drug shortages leave Mexican kids fighting for life

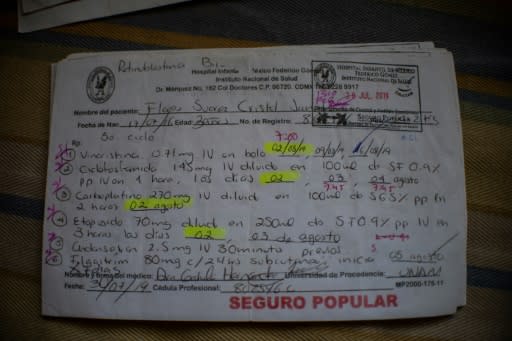

Five-year-old Dhana Rivas is fighting for her life on two fronts, fending off the acute lymphoblastic leukemia eating away at her frail body while her family simultaneously battles the shortage of cancer drugs plaguing Mexico. Recurrent drug shortages during much of her short existence means the frequency of life-saving chemotherapy has slowed. The shortages are partly a consequence of government policy and President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador's efforts to revamp the healthcare system by tackling waste and corruption. In August, authorities shut down seven Mexican factories producing methotrexate -- a major element of the anti-cancer cocktail. Breaks occurred in Dhana's chemotherapy in September and October of 2018, and again the following February, for lack of medicines. This was the case at the government clinic in her native Chiapas, in the south of the country. But following a transfer to Mexico City's Federico Gomez Children's Hospital designed to increase her chances of survival, nothing has changed. "The new government promised that there would be no more interruption of treatment," Dhana's father Israel Rivas told AFP. "That's not the case". And the situation is worsening. "There was not a single chemotherapy possible in January," Rivas says, his voice faltering. Dhana isn't alone. The parents of other young cancer patients have made contact with Rivas via social media. Together they raised the alarm over the lack of methotrexate, vincristine and other cancer medicines in hospitals around the country. "In Federico Gomez, there are 530 children affected, but in Mexico as a whole there are many more," said Rivas. He says he has received messages from parents living across the country, in Tijuana, Oaxaca in the south, Puebla in the center, Merida in the east, Guadalajara in the west, and Acupulco and Minatitlan in the south. According to the Health Ministry, some 7,000 minors fall ill with cancer every year. Catching and treating the cancer early gives them a 57 percent chance of survival, doctors say, but only if the right medicines are available. The medical team looking after Dhana believe they can maintain her treatment for just another month. - Cancer doesn't wait - For Crisanto Flores, father of three-year-old cancer patient Cristal, the lack of medicines is inconceivable. Of modest means, he was forced to move to Mexico City so that his daughter could receive treatment. And in January, the family went through one of the most critical moments of his daughter's illness when the main treatment needed for Cristal's therapy was unavailable. Flores knows that time is not in his daughter's favor, and his only recourse is to team up with other parents to try to put pressure on the government. "If the vincristine isn't available, the illness will gain ground," he said. His little girl has already lost the sight of one eye. Another anxious parent, Esperanza Soto, is desperately hoping that the shortages don't affect her four-year-old boy, Hermes Soto, who is just two months away from beating cancer. "We only have three cycles of chemotherapy to go," she says. Emmanuel Garcia in Baja-California and Alejandro Barbosa in the western state of Jalisco live nearly 2,000 kilometers (1,240 miles) apart. Both are battling to obtain the same medicines. "In Jalisco, there are three public hospitals affected by the shortage of medicines. We buy them from distributors certified by the government who bring them from abroad, which is very costly," said Barbosa. The price of vincristine has soared because of the shortages. In less than a year, it has risen by more than $23 to $118. Garcia has also signed up to the parents' pressure group since December. He says there are 81 sick children who, like others in Mexico, have suffered several interruptions to their chemotherapy treatment, despite a short respite when the hospital in Tijuana received a delivery. "And what about the others in southern Mexico?" he asked. - Shortage without end - In a desperate bid to make themselves heard, the parents staged a demonstration and briefly blocked access to Mexico City's international airport. The day after, Lopez Obrador was forced to address the subject, but without proposing a solution. "We will never run out of medicines," he promised, without further details. Some demonstrations bringing together a few families have taken place in recent days, but with little response. In Merida, the capital of the southeastern state of Yucatan, Flor Gonzalez, whose child Remi suffers from cancer, spends her days waiting. "Doctors are applying incomplete treatments," she said, relating the case of a child who had relapsed due to the use of a replacement drug. In Mexico, more than 26.4 million children have no access to any type of social security. A "popular insurance" scheme in place since 2003, but cancelled in 2020, was one of the few programs allowing children to seek treatment. For Dhana and the other cancer-stricken children, the countdown has started. The next few days will tell if the sword of Damocles swinging above their heads is lifted. Mexican four-year-old Hermes Soto, diagnosed with cancer, smiles outside the Children's Hospital in Mexico City Mexican toddler Cristal Flores' prescriptions are seen on a table at her house, in Cuautitlan, Mexico Mexican toddler Cristal Flores, diagnosed with cancer, rests on a couch at a relative's house, in Cuautitlan, Mexico Mexican toddler Cristal Flores, diagnosed with cancer, rests on a couch between her parents at a relative's house in Cuautitlan, Mexico Little Hermes plays outside his hospital in Mexico City In August, authorities shut down seven Mexican factories producing methotrexate, a major element in the anti-cancer cocktail