$1 Trillion of Corporate Bonds Today, Downgrades Tomorrow

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The amount of new debt issued this year in the U.S. investment-grade corporate bond market will reach $1 trillion today, by far the fastest pace in history.

The implications of that milestone depend on how you look at it.

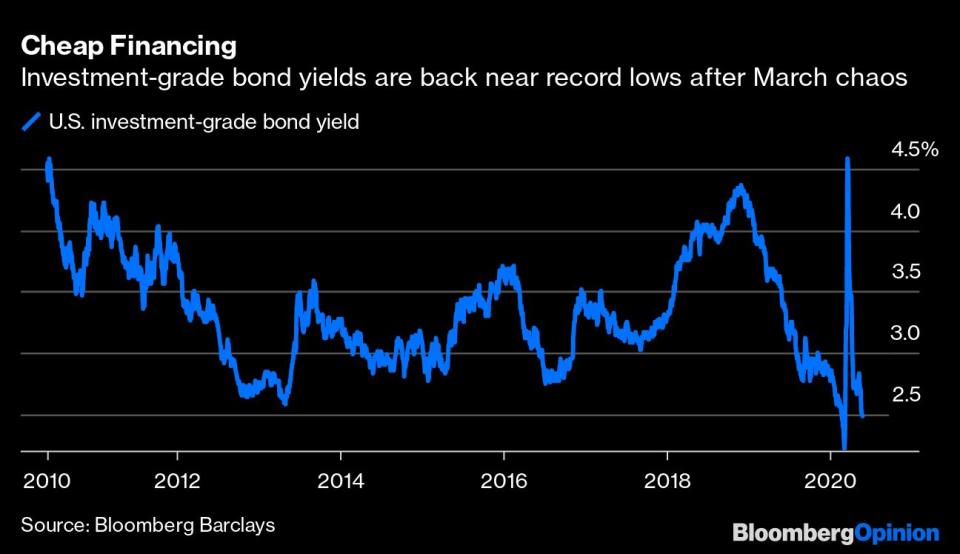

For businesses that had been ravaged by the coronavirus pandemic and the ensuing nationwide lockdowns, access to capital markets was a lifeline to get through the worst of the economic collapse. Sure, Carnival Corp. had to offer interest rates like a junk-rated borrower and Boeing Co. needed to include a so-called coupon step-up provision to offset jitters that it could lose its investment grades. But, in the words of Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, these deals avoided turning “liquidity problems into solvency problems” for brand-name American companies.

It’s worth remembering that until the Fed stepped in with extraordinary support for credit markets, averting widespread failures was far from guaranteed. Investors pulled a staggering $35.6 billion and $38 billion from investment-grade funds in the weeks ended March 18 and March 25, respectively. Before 2020, the previous record was $5.1 billion of outflows. I wrote on March 19 that bond markets were veering into a vicious cycle that could get ugly in a hurry — four days later, the Fed announced what would end up becoming a $750 billion backstop for corporate America.

Now, the Fed hasn’t actually had to buy any individual bonds yet, a fact that Powell seems proud to share. “We may have to be lending money to those companies, but even better, they can borrow themselves now, and a lot of that has been happening and that’s a really good thing,” he said during May 19 testimony before the Senate Banking Committee.

Most people would probably agree with that assessment, at least for the immediate future as the country grapples with restarting the world’s largest economy. But what about the longer-term view?

Here, the rampant borrowing paints a more sobering picture. As of late April, 1,287 issuers worldwide rated between AAA and B- by S&P Global Ratings were considered at risk of a potential downgrade, up from 860 in March and 649 in February. That surpasses the previous all-time high set in 2009. “Generally, we expect heavy credit erosion in coming months as issuers, especially those in the lower-rated spectrum come under heavy fire from poor earnings, continued difficulties in managing cost structures, and market volatility creating limited funding opportunities,” said Sudeep Kesh, head of S&P’s credit markets research.

That’s bad enough, but doesn’t even strike at the heart of the issue. Last year was supposed to be the beginning of a broad “debt diet” among companies that borrowed huge sums to finance mergers and acquisitions during the longest expansion in U.S. history. That didn’t end up taking place on a wide scale. Even a success story like AT&T Inc., which made headway in trimming its debt stack, still found itself back in the bond market recently, borrowing $12.5 billion on May 21 in what was the biggest deal since Boeing’s $25 billion blockbuster offering.

When it comes to companies directly impacted by the coronavirus pandemic or structural changes to their industries, the “big three” of S&P, Moody’s Investors Service and Fitch Ratings haven’t shied away from taking action. Ford Motor Co., Kraft Heinz Co., Macy’s Inc. and Occidental Petroleum Corp. are just a few of the “fallen angels” that lost their investment grades earlier this year.

The rating companies haven’t been quite as keen to react to high leverage metrics. I frequently refer back to this feature from Bloomberg News’s Molly Smith and Christopher Cannon, which found that of the 50 biggest corporate acquisitions in the five years through October 2018, more than half of the acquiring companies increased their leverage to a level that would seemingly merit a junk rating but remained investment grade on the assumption that they’d take that leverage down in the coming years.

Those expectations seemed ambitious in 2018, when the economy was seemingly invincible. Now, no one can truly expect companies to focus on right-sizing their debt. Corporate leaders are rightfully eager to raise cash to get to the other side of the pandemic, especially with all-in yields not far off from record lows. The vast majority of the $1 trillion in borrowing so far this year was by no means imprudent.

In the years ahead, however, the overhang from this issuance spree will inevitably weigh down credit ratings. A company with more debt presents a greater risk of missed interest payments than if it had fewer fixed obligations. Fortunately, for much of the previous expansion, firms had no issue finding investors willing to buy their long-term securities. That practice of rolling over debt and extending maturities might very well be the norm in the months and years ahead, too.

Still, if the first five months of 2020 are any indication, investment-grade bondholders will have to get comfortable with even more bloated balance sheets and the prospect of further credit downgrades. For better or worse, with the confidence that the Fed has their back, that seems like a risk investors are willing to take.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion

Subscribe now to stay ahead with the most trusted business news source.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.