France urges tougher pilot checks after Germanwings crash

By Tim Hepher

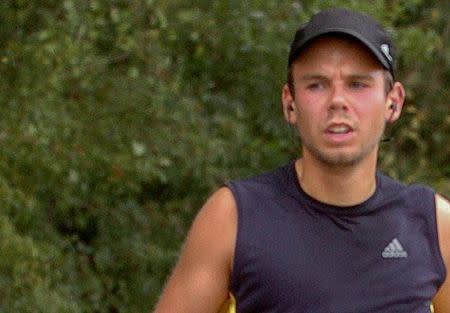

PARIS (Reuters) - French investigators have recommended tougher medical checks for pilots after uncovering fresh evidence of unreported concerns over the mental state of a German pilot who crashed his jet into the Alps last year, killing all 150 people on board.

France's BEA air accident investigation agency said a doctor consulted by Germanwings co-pilot Andreas Lubitz had recommended two weeks before the disaster that he should be treated in a psychiatric hospital.

The unidentified private physician was one of a number of doctors seen by the 27-year-old as he wrestled with symptoms of a "psychotic depressive episode" that started in December 2014 and may have lasted until the day of the crash, it said.

Investigators believe Lubitz, who had a history of depression, barricaded himself into the cockpit and deliberately propelled his Airbus jet into a mountainside on March 24, 2015.

The BEA said in its final report on Sunday that neither Lubitz nor any of his doctors had alerted aviation authorities or his airline about his illness, for which he was being treated with anti-depressants.

It urged the World Health Organization and European Commission to draw up rules to oblige doctors to inform authorities when a patient's health is very likely to impact public safety: if necessary against the patient's consent.

It also called for tougher inspections when pilots with a history of psychiatric problems are declared fit to fly.

None of the doctors who treated Lubitz agreed to speak to French or German crash investigators, the agency said.

"In Germany and in France, doctors are very attached to this notion of medical secrecy, but I hope there will be some moves there," BEA Director Remi Jouty told a news conference.

At the same time, the BEA called on airlines to find ways to ease the risks for pilots who may fear losing their job for medical reasons, such as loss-of-licence insurance.

Germanwings parent Lufthansa said it already offered insurance against medical grounding for young pilots.

GUIDELINES QUESTIONED

The report threw the spotlight on medical confidentiality guidelines in Germany in particular, a country where privacy is a highly sensitive issue due to extensive surveillance under Communism in East Germany and during the Nazi era.

Prosecutors have found evidence that Lubitz, who also had eyesight problems and may have feared losing his job, had researched suicide methods and concealed his illness.

Lubitz had been flying on a medical certificate that contained a waiver because of a severe depressive episode from August 2008 to July 2009. The waiver stated that the certificate would become invalid if there was a relapse into depression.

But the BEA cited a "lack of clear guidelines in German regulations" on when a threat to public safety outweighs the requirements of medical confidentiality.

It said Germany should not wait for action at a European level to remind all German doctors they have the option to breach medical confidentiality and report public safety risks.

The German pilots' union Vereinigung Cockpit said strict rules on data protection must be developed at the same time as drawing up criteria for suspending medical secrecy rules.

The BEA did not recommend any changes to the construction of cockpit doors, which were strengthened after the Sept 11, 2001, attacks in the United States.

Cockpit recordings show that Lubitz locked himself in and set the aircraft on its fatal course when the captain took a toilet break 30 minutes into the Barcelona-Duesseldorf trip.

Jouty said the doors had been designed to ward off possible terrorism threats from the passenger cabin that are still considered a greater risk than pilot suicide.

In a rift with European safety regulators, the BEA declined to endorse a recommendation that there should always be two people in the cockpit, a rule introduced by many airlines worldwide in the weeks following the Germanwings crash.

The BEA said previous possible suicide crashes, such as the loss of an Egyptair jet that killed 217 people in 1999, had not been prevented by a second person on the flight deck and called for a deeper study of the security and training implications.

(Additional reporting by Victoria Bryan in BERLIN, Editing by Angus MacSwan and Stephen Powell)